Imagining

A Gibney Journal

Issue 2

Letter from the editor

Over the past several months, Americans have suffered an onslaught of losses—the lives of family members, neighbors and beloved, iconic figures; homes and businesses consumed by fire or flood; livelihoods vanished; the crumbling of trust between people and between us and the societal institutions that should protect rather than endanger us. In the face of the unrelentingness of 2020, we respond, sometimes, with fear or cynicism, flare up in rage or shut down in despair.

It’s November as you read this, but I’m writing to you on a late-September morning after a night of watching what was labelled—at least, officially—a presidential debate, the first between Trump and Biden, broadcast and streamed for all to witness. For many of us who braved the experience, this appalling, frustrating spectacle laid out, in starkest relief, the clear choice before us. Not the choice between political candidates—though that is certainly true and of gravest concern—but the choice between heedless destruction and a path of personal and civic creativity.

Artists model how we can walk this path. That has always been a core principle at Gibney, and let us underscore that now, again and again, as a responsible institution and a responsible community. Artists, and those of us whose work supports artists, can lead the way. No matter how this year’s election turns out, reparative work remains for us to do. We will need freed-up thinking, liberated speech, energized convening and imaginative collaboration. We will need to nurture ideas that set possible futures in motion.

In that spirit, let us greet, with excitement and anticipation, our bold writers for this second edition of Imagining:

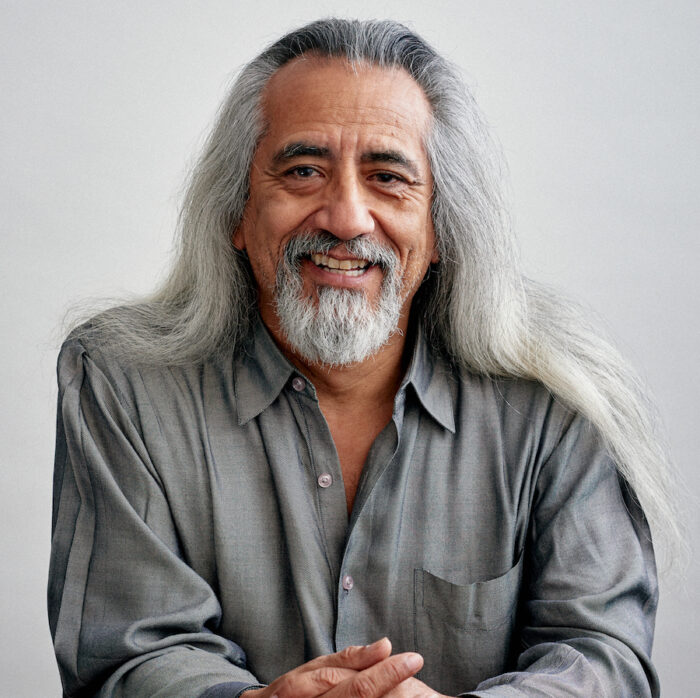

George Emilio Sanchez, residing in gentrifying Brooklyn, approaches the concept of “place”—of home—from the perspective of a Latindio artist, activist and student of the US Constitution and Federal Indian Law.

Antuan Byers, a founding member of the pioneering Dance Artists National Collective, talks with three Black women dance artists—Fana Fraser, Paige Fraser and Annique Roberts—about self-esteem as a force amid institutional conditions that often keep dancers silent and exploitable.

Conrhonda E. Baker reads all your slogans and institutional statements of solidarity and fires back a slew of questions. Get real or get lost.

zavé martohardjono’s wide-ranging conversation with artist colleagues Raha Behnam and mayfield brooks gave me life. And when I say artists gonna lead the way? THIS.

Our November issue rounds up with a look at the first posthumous book from ntozake shange—her personal celebration of oft-undersung Black artists in dance—and a letter from a dancer in Tehran, Iran, for whom Gibney’s virtual classes, first offered during pandemic shutdown, have become a lifeline.

Thank you so much for your fantastic responses to our first issue in September! We have more for you coming up in January 2021, and we can’t wait to share.

Let’s survive this year and make the next year one to remember for all the right reasons!

Eva Yaa Asantewaa

Senior Director of Artist Development and Curation

Editorial Director, Imagining: A Gibney Journal

Thursday, June 4, I sat in my apartment at 177 Adelphi Street, at my kitchen table, underneath swirling police helicopters and a constant drone of police sirens surrounding Fort Greene, trying to complete my homework for my Federal Indian Law course, of a Masters program in Indigenous Peoples’ Law, while I was unable to quiet my parental nerves over the fact my 20-year-old daughter was out protesting in the streets with hundreds of others, and I was questioning her decision to protest, not because I didn’t think she should, but because we were still in a lockdown moment because of the Covid pandemic and, in the midst of the outrage over the police violence Brooklyn was demonstrating against, the dreaded fears of Covid contamination, and a deadline for my homework that was fast approaching, I suddenly realized the intersection of a pandemic, Black Lives Matter, my daughter’s health versus her activism, and the lopsided history of this nation’s conflicts with our indigenous people all came together in a whirlwind of memory and history, and it all elevated me out of my kitchen chair at 177 Adelphi Street to see, know and feel how the past we know and don’t know lives in the now blazing a trail into a future we can only pray will not replay what we have failed to acknowledge.

And I began to reflect on how and why I live where I live and how the place of where I live feeds the work I make. And the work I make feeds the place I live.

Following the election of the Occupier in 2016, I distinctly recall how he remarked in response to a report of someone burning a U.S. flag by expressing how this individual should go to jail and be stripped of their U.S. citizenship. That’s when it hit me: No one can take away our First Amendment rights. So, in 2017, I inaugurated an initiative consisting of a network of ‘spaces’ to stand up and publicly proclaim defense and support of our First Amendment rights, namely freedom of speech and the right to assembly, and I named it First Amendment Sanctuary Spaces. It is a collection of 35 cultural spaces, mostly performance presenting spaces, but it also includes four locations tied to organized religion. The main emphasis is linking the concept of a “space” and, in this case, location. Absent other venues or locales, these locations vowed to protect the rights provided to us by way of the amendments that are the arms and legs of our Constitution. Three and a half years later, it is evident this initiative relied on the recognition of how sacred something like “place” can play when reflecting on the relationship between rights and personhood and how people need to be able to speak out because dissent is the lifeblood of a free and open society. My individual rights are everyone’s rights. And, in the public domain, it is essential to have, and maintain, places where the public can embody and practice these rights and flex our democratic muscles.

Sanctuary is a place for rest or refuge. A place of peace or one of a religious nature where the holy resides. But sanctuary is directly connected to a specific place where these values and ideals can exist. A place to breathe. A place for the soul or spirit of a person or people. A shelter. A home. A sacred place.

Since the inauguration of First Amendment Sanctuary Spaces, I have simultaneously delved into a creative investigation into excavating how the U.S. Constitution impacts lives and belief systems and serves as a critical template for how we learn, or are taught, to co-exist. As a direct outcome of this ongoing search, I began a performance series named, “Performing the Constitution.” The next performance of this series is titled In the Court of the Conqueror, and it will interweave autobiographical experiences of my family’s biased perceptions of indigenous people with a historical investigation of the 200-year-old history of Supreme Court rulings that have diminished, diluted and upheld the Tribal Sovereignty of Indian Country. This research began years ago.

Between March and July 2020, I have been living in Brooklyn in the middle of a catastrophic global pandemic that forced me to think locally. All New Yorkers encountered two viruses that profoundly related to public health: first, the COVID-19 virus, and then, the virus of police violence that is centered on race. The two viruses unnecessarily took the lives of innocent people that need not have been sacrificed. And both viruses are directly linked to the government infrastructure of a so-called democracy where our response to these viruses tells a story of how we identify who we are and what we stand for.

Black Lives Matter has jolted this country from its complacent slumber regarding race and ignited the minds and imaginations of all its inhabitants. As a brown-skinned Latindio (1 Latino + 1 Indio = 1 Latindio) artist who has been making performance works around race and identity since 1992, I am not surprised by what has erupted since George Floyd’s murder at the hands—I mean the knee—of police. No, this cultural upheaval is long overdue. It’s a new chapter in the ongoing struggles of People of Color in making the words of our Constitution concrete and real . We have a ways to go before the arc of the universe emanates from a place of justice but, headed in that direction we are.

In the middle of the lockdown, where 24/7 became no way out, I enrolled in a Masters in Legal Studies in Indigenous Peoples’ Law, an online, asynchronous program out of the University of Oklahoma, the home of Indian Country. If I were not in a lockdown situation where it was a risk to leave my apartment, I may never have enrolled in this program. But as I was doing the research for my next piece, and attempting to learn about the history of Federal Indian Law and Policy in the U.S., I suddenly realized in the flash of a pandemic moment, Why not? If I am going to be reading and researching this history regardless, I might as well get a Masters in Legal Studies at the same time.

I applied, was accepted and enrolled in about eight days. Only after receiving my first assignment did I realize it was the effects and impact of Covid-19 that drove me to become a graduate student…again. All in the name of “artistic research.”

I also realized it was the place where I was living, Brooklyn, and being in my place, in Fort Greene, that played a significant role in getting me to do something I never imagined. As the police sirens and helicopters droned on, I remembered how Fort Greene once served as a stop along the Underground Railroad and the emancipation of enslaved people in the South migrating to freedom in the North. At least on paper.

And that realization ricocheted off my kitchen walls and shook me from head to toes while reading and researching Federal Indian Law in the middle of the two viruses running through the streets of Fort Greene. And, in the action of learning, I felt the pulse of the meaning and significance that “place” holds, or doesn’t hold, on our experiences and interactions within and outside our communities we identify and find common ground with, or not. I live less than a mile from the Brooklyn Hospital Center where that place was overwhelmed by the ravages of Covid-19, and less than a mile from the Barclay’s Center where demonstrators and police first clashed or, rather, where demonstrations were first clashed over by the NYPD. And while the gnawing sound of the police helicopter hung over my apartment building, I read how the legal definition of place, “jurisdiction,” has played out for centuries for the first sovereign of this country, a place legally named “Indian Country.”

One of the key concepts that has turned my understanding of U.S. history upside down is the fact that the U.S. houses three sovereigns. Those sovereigns are made up of the federal, state and tribal governments. On paper at least. And this has become a fundamental understanding in Federal Indian Law, how tribes and tribal governments form one of the sovereigns that are part of the legal infrastructure of our democratic republic. Although Indians, indigenous nations and tribes lost title to the land as per the Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823) Supreme Court case, Congress and the Federal Courts acknowledge tribes maintain tribal sovereignty from “time immemorial.” But, as anyone might guess, for over 200 years, our courts have not consistently recognized this fact. The court rulings go drastically back and forth on this question when it comes to specific cases, but no longer do legal professionals and scholars deny that tribal governments form a sovereign of the U.S. While Indian nations exhibit immense diversity in their cultures and communities and cultural practices, there are certain common denominators that distinguish them from Anglo-American culture. And one of those core beliefs is the meaning and significance of place as seen through the prism of indigenous identity. And this is exactly what anyone can verify when being exposed to and learn about Indians and their history after European contact.

From the moment English settlers—as well as settlers from France, Spain, and the Netherlands—arrived on these shores, Indians and Indian Country have lost more land, and rights to their natural resources, at a rate no other people can match. Between the two most harmful statutes that have taken lands from the Indians—The Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the General Allotment Act of 1887—Native Nations have had their collective backs to the institutional infrastructure whereas the federal government has always had the last word when it came to deciding which sovereign had the legal “jurisdiction” to do as it saw fit. So, as I find myself surrounded by two pandemics that have taken the lives of so many, and within histories that have perpetuated this violence for centuries, I look at the clash of cultures, ideologies, and identities currently raging through the streets of our urban centers and small towns. I cannot stop seeing and hearing how the seeds of violence and racial superiority were laid bare when the white settlers first landed on Native lands and began a narrative that made a promise it has failed to keep:

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Reading these words from the Constitution makes me pause with a deep sense of remorse and anger at how the dominant narrative of this country says one thing and does another. And yet, although the light of hope should have been expelled long ago, we Latindios and Indians must and will find paradigmatic ways in which tribal communities and ally organizations are collaborating together to change the tsunami of Settler Colonialism into one where Indian Country can subsist, thrive and continue, through tribal self-governance and tribal sovereignty, into the future and time immemorial. Until then, the words of the Constitution do not speak to Justice as we feel it in the places where we live.

George Emilio Sanchez is a writer, performance artist and social justice activist who lives in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. He is currently developing his next solo performance work, In the Court of the Conqueror, that is commissioned by Abrons Arts Center in New York City. His new work will address the 200 year-old history of Supreme Court rulings that have diminished, overrode and upheld the Tribal Sovereignty of Indian Country. This new work is a part of his “Performing the Constitution” series. He teaches at the City University of New York’s College of Staten Island and he is a Social Practice Artist-in-Residence at Abrons Arts Center. He recently completed his thirteenth year as Performance Director of Emergenyc, and he serves on the Executive Council of his union, the Professional Staff Congress.

Photo of George Emilio Sanchez by Zack Garlitos.

Despite the violent and dangerous challenges presented by the double bind of racism and sexism, Black women have been, and continue to be, the backbones of our households, communities, civil rights movements, and even our labor unions.

The Washerwomen of Jackson, the first labor union in Mississippi, was formed by Black women in 1866. In 1942, Sue Cowan Williams represented Black teachers in Little Rock, Arkansas in the case of Morris v. Williams, disputing the salary disparities between teachers based on the color of their skin. To secure health insurance for herself and her eight kids, Hattie Canty, a widowed single mother, worked as a maid at Maxim Hotel-Casino in Las Vegas. Later she was elected President of the Culinary Workers Union 226, to then lead the union for 6.5 years through the longest strike in labor union history. Throughout history, even when locked out of union halls, Black women have innovated and continued to be leaders on the frontlines of the labor movement, challenging inequitable systems of power.

Although Black women have historically had higher labor participation rates, they still make less than their white counterparts, and they rarely hold leadership positions. In 2018, Black women were paid 62% of what white men were paid, according to the U.S. Census. That means that it takes Black women 19 months to be paid what the average white man makes in a year. In 2015, through a survey of Black women union members and organizers, the Institute for Policy Studies found that 65% of Black women union workers said that they aspire to be union leaders, while only 3% reported having held elected positions.

So, what does this look like in our dance spaces? I had a conversation with Fana Fraser, artist, performer, and rehearsal director of Ailey II, Paige Fraser, disability activist, founder of the Paige Fraser Foundation, and performer in the National Tour of The Lion King, and Annique Roberts, senior dancer and rehearsal director at Ronald K. Brown/EVIDENCE, and adjunct professor at NYU Tisch School of the Arts. These three Black women spoke with me about their experiences navigating the dance field, their relationship to power, and their thoughts on unionization and collective action.

This interview has been edited and condensed for style, clarity, and length with the consent of all participants.

Antuan (he/him): What is your experience with unions?

Paige (she/her): I’m AGMA (American Guild of Musical Artists) through the Lyric Opera, and Actor’s Equity through The Lion King.

Annique (she/her): I have never been a part of any union, but I have been on the receiving end of the reasons why we need a union, and that is actually what inspired me to apply for Law School. I’ve been on the receiving end of the exploitation, being taken advantage of, and discrimination—all those things—and I’m like, “No, that’s not okay!” But, also not feeling like I have the power to say “That’s not okay.” I don’t understand my rights well enough as an employee to say “That’s not okay.”

Fana (she/her): That’s really interesting. Yeah, I was a member of AGMA in, maybe, 2013 or 2014, while in an opera at the Metropolitan Opera, so that was the extent of me being part of a union, but I feel like my work recently has helped me observe a lot. I mean, I observe everything. I’m taking it all in and making little notes in my brain about what’s happening, what’s not happening, who’s doing what, why and how, when, and where, etc. So, I would say the experience has been an observatory relationship. Observing how dancers in a union function, day to day, and by being on the receiving end of some of those stories.

Annique: You’re the rehearsal director for Ailey II, right?

Fana: Yes, that is my current role.

Annique: So you’re not part of a union when you’re rehearsal director? Just the dancers?

Fana: The first company dancers, yes.

We took a moment, off the record, to reflect on recent events as well as our experiences of trauma within the dance world.

Annique: I used to think it was just an older-generation thing. I think part of it comes from these old traditions and the residuals of that. Then I think there’s just this power imbalance, that belies the troubles we see right now. Some of that traditional stuff is still seeping in, but as new generations are coming in, it’s nice to see them starting to challenge that.

Fana: It’s the same transgenerational, intergenerational traumas. We’re in this trauma-porn cycle that is disruptive and toxic to all of us. We’re at a moment when our generation can make a shift. How much do we push? This is where unions come in. How much do we work to set new foundations? The people who are holding and gripping on, just need to let it go. [She sings the chorus of “Let it Go” from Disney’s Frozen]

We don’t have all the answers, but we have a different way of thinking and approaching this. We have been shedding a lot that doesn’t serve us anymore. We’re giving ourselves and our souls in this art form. We need support. It’s about infrastructures of support. What are the infrastructures of support that we need to work from a place of holistic well-being? It can be done. It’s not impossible.

Paige: A healthier way of working. When I joined West Side Story, I remember they gave me Laduca’s that were a hair too small, and I was too nervous to say anything. My colleague was like “Girl, they have the money! You better let them know these shoes are causing you to get blisters!” The fear that I had for so many years of “Let’s just make these work,” to then being in a space where it’s like, “Oh! We have another shoe for you.” Being comfortable and knowing what the standard is, and not being afraid to say, and ask for what you need. As Fana was saying, “Say when something’s wrong.”

It was incredible. Like clockwork, we got our breaks. Even how the rehearsal schedule was sent out to us. You literally just show up and do your job, which was just such a breath of fresh air, especially coming from where we didn’t even get schedules. We were excited to be there and eager, but there were just so many unanswered questions that we kind of knew something was wrong. We were just happy to be employed. I think that’s something we have to talk about. Wrong is wrong, whether you’re employed or not.

Annique: I think there’s also this expectation that you’re supposed to just take whatever they give. You should just be happy that you have a job. It’s like, “Wait, wait, wait! You need me. I matter. I add value, so you should treat me with some level of respect.” I’ve found that when there are subpar working conditions, you’re kind of expected to just sit and deal with it. A lot of older-generation company members were used to these conditions. They were okay with it. I remember we were on tour somewhere, and the space that was reserved for us to warm up and have class was dirty. I said “I’m not doing this,” but just about everyone else in the company, especially the older folks, were like “This is what the director said to do, so this is what we’re doing.” I took myself to another spot that was cleaner, and I decided at that point, I was not going to do that. Most of the time, you just fall in line, and I find it so unfair that you’re expected to just accept these conditions that don’t reflect your values. You think I’m trash. That’s what that makes me feel like.

Fana: For me, this always goes back to how we are trained in the studio. When leading classes, I have been trying to incorporate voice so much more with the dancers, so that it’s not just me in there talking to myself. “I know you guys are listening, but I want to hear you respond with your actual voices.” That practice of speaking up with your voice to say “Hey, this floor is nasty, and this is not okay,” or “Hey, I feel uncomfortable,” “I feel unsafe,” or “This feels like an unhealthy situation.” That voice limb has to be exercised, especially with dancers who are so physical, sometimes more reserved, and less comfortable speaking. Then we, as directors, can say “That’s a good question, let me try to figure it out.” “Let me try to find another way to say this.” So they are practicing feeling empowered in the room and can say “Hey, you know what? How can we organize ourselves?”

We have to practice speaking up, or else what is the union going to be made of? Nobody saying anything? We need to talk more. There needs to be more space for talking, and that goes back to that idea of what you’re saying, Annique. It’s how we’ve been raised. Dr. Joy DeGruy talks about Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome, and my mind was blown. We have been trained to have no back talk. It’s the same thing, and it’s not serving us. It protected us at one point, but it’s not helping us anymore.

Paige: I agree with that too. Joining Ailey II, I was a senior at Fordham. My first tour was in Europe, and I was so nervous. You don’t know how that’s going to be. You don’t know what to expect. You just have to figure it out, and I feel like that’s been most of my career up until late. Figuring it out. Back to that sink-or-swim mentality, and it isn’t healthy.

Annique: Especially, for us as Black women, there is this double bind. Not only do we have to try to appeal to this white male standard, but we also have to try not to be the aggressive woman or the angry Black woman. We have this narrow space that we get to fit into, and we can’t go anywhere outside of that, or else we’re going to be seen as something not positive, something not deserving of award, something not deserving of recognition, or something not deserving of promotion. If we don’t toe this line and fit exactly in our place, then we won’t achieve what our hard work has prepared us for.

Paige: It’s not only happening to ballerinas. It’s happening in the contemporary dance world as well, to the point where I had to flee to another predominantly Black company to find myself again and rediscover the parts in myself that were actually beautiful.

Fana: Paige, you used the word “flee,” and it really struck me. I’m like, “Yeah, we feel like we’re just on the run all the time,” and that’s not right. No, I should not have to flee. These people need to be trained. I’m not in the wrong. These people need to be seriously schooled and trained, because I’m not going to keep running for the rest of my life. That’s too much.

Annique: I think that speaks to what Paige was talking about. For all that time, she always thought it was her. You’re at this kind of inflection point where what you know to be right, moral, just—or whatever—is colliding with reality. And it’s also up against you trying to pursue your dream. So you’re really just trying to figure out “Do I take this so that I could possibly achieve what it is that I want to achieve?” “Do I walk away from this?” “Will I find another opportunity that keeps me on this pathway towards my goal?” Then, as a young person, it’s like, “Wait, what?” You don’t have anyone sticking up for you. That’s where the unionization piece can be so helpful. As you guys know, I haven’t worked with a union, but I read a book a while back about the myths of unions. Basically Myth Busters for unions. It seems to me, that if choreographers are pushing back against unionizing, then it’s because they don’t truly understand the purpose of a union, and they don’t realize that the union actually is there to work for them, not so much against them. It’s a negotiation.

Paige: I was just going to segue into how directors take advantage of dancers.

While dancing for one of my previous employers, I was asked to do the company’s social media. Although I didn’t mind helping out, it quickly became an additional job that I should have been compensated for. It’s really easy to exploit those of us who take on these responsibilities out of deep care for the success of our employers and colleagues. In many cases, as I’ve experienced, directors task dancers with responsibilities that exist outside of their contracts, which ultimately amounts to free labor and added stress. I think that moving towards an equitable future in our field looks like compensating dancers and creatives alike for all of the work they do.

Annique: Makes me think about the place that’s left for us, or relegated for us as Black women in the dance space and in the dance community, and the roles Black women have been allowed to occupy. It has always felt like it was in service to the men that were in charge. It never feels like you truly get equal footing, even if the role calls for it. When we, as Black women, make it to the role of leadership or management, there then lies this conflict with, “to what extent do you hold their feet to the fire?” “To what extent do you make them accountable?” Now you’re in this position, you’ve got a little bit of power, and people will listen to you a little bit. How do you use that? We still end up with the same challenge of “Do we speak out and maybe jeopardize our health insurance and our job, or do we sit back and let a few things slide so that we can stay in this place?” I mean, you’ve heard Kamala Harris talk about it. So, it’s definitely not specific to us and dance.

Paige: And I think it’s important to honor your spirit. That’s something I’ve learned as I’ve gotten older. I wish I had learned it a few years ago. Even being in a union cast, yeah, we are protected by the union, but there is still stuff that goes on that isn’t right.

Fana: For me, all of this, thinking ahead, goes back to what we were saying earlier. Working from a place of healing, rest, and enjoyment. Enjoying the things that we love. It’s for us to get a chance to just be able to breathe. “I can’t breathe.” (She evoked the words of two Black men—Eric Garner, George Floyd—as they were killed by cops.)

We need to be able to have places that we feel that we can retreat to and be able to take a few deep breaths. For moving forward. For the next, and the next. What are we fighting for? It’s for them. It’s for our well-being. It’s for our health. It’s our right to feel good.

Antuan Byers is a dancer, creative entrepreneur, and arts activist based on Lenapehoking Land (Manhattan, NY). He is a graduate of the Ailey/Fordham BFA Program, and holds a certificate from the Parsons School of Design. Antuan has cultivated artistic partnerships with brands such as Acura, Barney’s NY, Brooklinen, Nike, Jaguar, and Urban Outfitters, and global modeling campaigns including ASICS and Capezio. After touring internationally with Ailey II, he returned to Lincoln Center to rejoin the Metropolitan Opera Ballet, where he is currently performing a repertory with works choreographed by Kim Brandstrup, Philippe Giraudeau, Lorin Latarro, Sue Lefton, Mark Morris, Alexei Ratmansky, Susan Stroman, and Christopher Wheeldon, among others. Antuan hosts The LLAB on the Pod de Deux podcast, a series on racial justice in the dance world, is a steering committee member of the Dance Artists’ National Collective, and is a founding member of the Black Caucus at the American Guild of Music Artists. He is also the proud Founder/CEO of Black Dance Change Makers.

Photo of Antuan Byers by Eric Politzer.

Born and raised in Trinidad and Tobago, Fana Fraser is an artist, performer, director, and creative consultant based in Brooklyn. Her artwork is rooted in a contemporary Caribbean aesthetic and framed by narratives of eroticism, power, and compassion.

Most recently, she served as the Rehearsal Director for Ailey II. Her performance work has been presented at venues including BAAD!, Brooklyn Museum, Gibney, Wassaic Project, Issue Project Room, Knockdown Center, La MaMa Moves!, and Trinidad Theatre Workshop. As a performer, she has worked closely with Camille A. Brown and Dancers, Samita Sinha, and Ryan McNamara. She has also worked as a guest artist for the MFA Dance program at Sarah Lawrence College and the BFA Dance program at University of the Arts.

Fana was a CUNY Dance Initiative 2017-18 resident artist; a Movement Research 2017 Van Lier Fellow; a participant in the inaugural MANCC Forward Dialogues choreographic lab; a 2016 artist-in-residence at the Dance & Performance Institute in Trinidad & Tobago and a resident artist for Dance Your Future 2016 – a project partnership between BAAD! and Pepatián.

Fana was recently shortlisted for the 2020 BCLF Elizabeth Nunez Caribbean-American Writer’s Prize and is currently a full spectrum doula in training at Ancient Song Doula Services. fanafraser.com

Photo of Fana Fraser by Whitney Browne.

Paige Fraser is originally from The Bronx, NYC. She graduated from the Ailey/Fordham BFA program. Paige danced professionally with Ailey II, Visceral Dance Chicago, and Deeply Rooted Dance Theater. In 2016 she was featured in an INTEL commercial “Experience Amazing.” She is a Princess Grace Award recipient (2016) and Dance Magazine’s “25 to Watch” (2017). Ms. Fraser is the co-founder The Paige Fraser Foundation (TPFF) which aims to create a safe space for dancer with or without disabilities.Theatre Credits: West Side Story(Lyric Opera) and The Lion King National Tour. paigefraser.net thepaigefraserfoundation.org

Photo of Paige Fraser by Nomee Photography.

Annique S. Roberts, originally from Atlanta, Georgia, is a veteran dancer and the rehearsal director for Ronald K. Brown/Evidence, A Dance Company. She joined Evidence in 2010. She was a senior dancer with Garth Fagan Dance for 6 years. Roberts was nominated for a 2013 New York Dance & Performance (Bessie) Award for Best Performer. She is currently an Adjunct Professor of Dance at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts.

She earned a BFA in Dance from Howard University and an MA in Arts Administration from Savannah College of Art & Design.

From 2011-2016, she co-founded and directed the Atlanta Spring Dance Series, an annual one-day dance workshop event that raised money to assist young dancers with professional development opportunities.

Photo of Annique S. Roberts by Shoccara Marcus.

Note for my Black brothers and sisters: Don’t hate me–hear me out…All skinfolx are kinfolx. We all got some family members we love AND don’t agree with their actions or ideology. It is ok; we need everyone in this movement. We all have a purpose. Collectively, we’ve given hundreds of years of undeserved grace to white folx, and we’ve internalized their lies about our worth along the way. It’s time to redirect our love and compassion to our skinfolx and give white people accountability instead. No more hall passes. So, below is just one way that I am shifting my focus. I hope you feel my love for you in these words.

This year, I thought that the arts and cultural sector needed a field-wide cultural equity assessment. However, I don’t think that will go far enough. More survey data will not yield results. Instead, they will continue to disrespect and humiliate the artists who won’t see a dime from reactionary philanthropic grant initiatives and relief funds distributed by national, regional, and community foundations.

I cannot support such a waste of time. Instead, every organization needs to undertake an internal social justice audit. Oh, and by the way, groups led by those who self-identify as Indigenous, Native American, African, Black, Latinx, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander, Arab, or Middle Eastern are exempt. Please keep doing what you’re doing, fam, and use my framework to assess your partnerships. Now, if you serve one of these populations and your artistic AND administrative leadership does not self-identify accordingly, then you need a social justice audit because you’ve got to acknowledge some cognitive dissonance.

It’s been a whole six months since the bottom fell out and trading videos of violence against Black bodies on social media became a national pastime. So, I want answers from every organization that issued a solidarity statement. I want to know:

- Did you mean what you said?

- If you are for real, how far will you go to support us?

- Are you going to run our coin?

- What monetary benefits and other resources are you providing to your non-white staff as compensation for participating in your learning, equity assessments, and cultural change initiatives?

-

- How many of your job descriptions, commission offers, partnership proposals, and requests for labor included upfront salary, benefits, compensation, hourly rate details? Failure to do so means you fail Anti-Racism 101.

- How are you acknowledging how your institution has contributed to historical and current economic disparities?

- How are you redistributing wealth, resources, and access to facilities? Detail the circumstances of your property acquisitions, with special acknowledgment on the benefits garnered from gentrification and discriminatory lending practices.

- How are you making space?

- What are you doing to make your space physically and mentally safe? Share a bit about the conversations you’ve had with Black artists and managers to discern if they can show up and contribute fully to your primarily white institution.

- How and why are you ill-equipped to resource and present Black artwork? Explain why asking to make Black products palatable for audiences is asinine and assimilative. FYI–I’m boycotting folx who are unwilling to cede space consistently.

- How many times have you gotten out of the way?

- Do you understand that a contract with one is a contract with our tribe since we don’t roll alone?

- Will you treat our collaborators with respect?

- After asking for solutions, will you listen, or do you ignore suggestions?

- Will you stop labeling calls for cultural competency as cockiness?

- Do you understand why tech riders explicitly detail:

- entreaties for Black volunteers, ushers, and lobby attendants;

- requests to play curated music pre-show, during intermission, and post-show; and

- recommendations for particular actions that respectfully rebuff white supremacist and disrespectful rules and protocols?

- How many times have you asked a Black artist to create work for you that exploits Black pain or is in response to the current climate?

- Why are you unwilling to pay for Black joy or allow Black artists the freedom to rejoice as outlandishly as they see fit?

- Are you zealous about citing sources, naming influences, and appropriately attributing inspiration?

- How are you paying respect and providing credit in playbills, programs, websites, and other external/internal promotional materials for previous, current, and upcoming productions?

- Why do your education programs devalue movement forms derivative of African cultural traditions and staunchly defend codified Eurocentric pedagogy? Aside: I believe we’re gonna continue to have problems in the concert dance presenting realm until all levels of dance education give the broad-ranging manifestations of African movement genres–ranging from West African forms to percussive techniques–access to studio space, class levels, financial resources, academic scholarship, and culturally competent critique on par with ballet and modern.

Whew, chile! Take a deep breath. You’ve completed the discrete question portion of your audit. Thanks for these answers! Now, go grab some snacks, water, and your favorite pen. The next section is a discussion portion focused on providing indisputable evidence. You are required to show your work. If it’s been a few decades since you’ve engaged this concept, I encourage you to find a middle school math student. They can help you understand what level of detail is sufficient for a passing grade. Additionally, I will not accept revisions post-submission. Answers rooted in humility, openness, and transparency will receive bonus points.

- Prove why the mere existence of Black folx, enhanced by artistic and cultural expression, is the purest, rawest, most nascent form, most rebellious, and a most liberatory act of social justice.

- True or False (include rationale): The statement “the art speaks for itself” is a half-baked notion that diminishes the fact that the environment in which art is made, marketed, commodified, and consumed has an impact and matters.

- Tell us why it is ludicrous to think that Black art can thrive in spaces built, designed, and re-engineered to support white supremacy and racialized oppression.

- Talk about a time when you were not transparent about your budget or available artist fees.

- Describe a conversation where a Black artist or manager had to ask or clarify the compensation amount, rate, and/or payment schedule for a project because your organization did not provide adequate information at the outset of contract negotiations.

- Examine the strategies and tactics you use to negotiate with creative beings, particularly methods of haggling, pushback or significant price cutting when you do not have knowledge of the technical rigor and aesthetic nuances of the craft, or respect for/understanding of the necessary curatorial process.

- List the ways Black cultural workers deal with/respond to your refusal to “do the work,” lack of cultural awareness, and remedial understanding. Then share how this influences rates and fees.

- True or False (include rationale): Black artwork is priceless, invaluable, and necessary. A request for extra resources is often viewed as greed rather than a level of compensation directly tied to the amount of emotional labor imposed by working in a primarily white space. Note: Blackfolx are doing you a courtesy, extending mercy, and offering grace by monetizing our brilliance and ascribing a dollar value to our cultural outputs. It is a kindness for your sake, so treat it accordingly.

- Count the number of lies you’ve told about Black artists and managers along with the number of times you’ve used an acronym or label to describe a group for which you have no authentic relationship.

- Provide a sample grant narrative/description of diversity programming that is clear about the conditions under which folx survive rather than relaying “disadvantage” as an inherent character trait.

- You were working with a badass Black artist or manager who recently left your project/organization (voluntarily or not).

- Count the number of times you punked out of difficult conversations and chalked these departures up to “personality differences.”

- Discuss how you garnered feedback on the ways you pushed them out.

- Detail the mechanisms for senior leadership and board members to hear hard truths, learn, adjust internal culture, augment processes, and account for new needs.

- Consider a time when you challenged what you thought was true about the development of a movement language.

- Was it easy to find sources not written by white cisgender men?

- Were you able to discern who actually holds the full record of what truly happened?

- Can you denote the moments in time when the technique was appropriated and commodified for the entertainment of primarily white audiences?

- Sidebar: If you haven’t undertaken this exercise, may I recommend you start with Tap. If you were not aware of Juneteenth, then under what type of magical thinking do you subscribe that allows you to revel in mythology and believe that you know with certainty how a Black art form developed? It’s kinda absurd. Spoiler alert–Tap has more hidden figures than NASA!

Okay, okay…I know…lofty claims were made in your statements out of good intentions to become anti-racist or operate as an ally. Well beau real talk, just like you have no right to label us, you cannot claim the mantle of an anti-racist ally for yourself. This is not entrepreneurship; you don’t get to choose your title. Being a scholar of Black history will teach you that the status of “ally” is hard-earned and only ascribed to you by the communities you have harmed. You also have no right to persist as a primarily white institution anymore. Resist conformity and white solidarity. If the composition of your board, staff, commissioned artists, vendors, 1099 contractors, etc. have not dramatically changed by June 2021, let me be clear: You are choosing racism. PERIODT.

So, time for a 6th-month check-up; know your numbers; go get a baseline now. You have time to course-correct. Any action less than those aimed at ultimately abolishing institutions, systems, and best practices SUPPORTS AND FEEDS THE THING YOU ULTIMATELY SEEK TO DESTROY. Unwillingness to embrace radical ideation and to put real thought and effort into tearing down culturized racism is a clear indicator that your brain stem is blocking the processing of the principles of anti-racism. Let go, stop over-intellectualizing, and allow reality to travel from your brain to your heart center.

So, be prepared to step to me with answers when you present commissioning, speaking, or training opportunities. Get ready, ‘cause I’m gonna ask…

Are you for real or nah?

DISCLAIMER: In addition to The Bese Saka, I work, serve, and am a member of several organizations. This contribution is my own and does not necessarily reflect the views, strategies, or opinions of any of those entities.

Chief Copy Editor: The Bese Saka

Conrhonda’s passion for the performing arts is grounded in her dance background, sparked by taking after-school classes at a county-wide recreational facility in rural northeast Georgia. Having grown up with limited access to the arts, she understands the importance of exposing children to creative outlets and creating opportunities for artistic expression. She founded The Bese Saka in 2018 as a way to live out her Christian faith by actively intervening and building equity into the process of securing institutional funding support.

She currently serves as an advisor to The Albireo Group and her fundraising, government affairs, and program development experience developed through work with South Arts, Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts, Alabama Dance Council, Vulcan Park and Museum, Birmingham Museum of Art, and Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation. In addition to being a member of Women of Color in the Arts, the inaugural Port Authority Bus Terminal Advisory Committee, and Liquid Church, she serves on the Board of Directors for SOLE Defined and the Junior League of Montclair-Newark. Her favorite Bible verse is 1 Corinthians 9:26 (NLT Version). She holds a Master of Arts Management from Carnegie Mellon University and a Bachelor of Arts in African American Studies with a minor in Dance Education from The University of Georgia. www.thebesesaka.com

Photo of Conrhonda E. Baker by Jean Melesaine.

This text plucks from two hours of conversation between zavé martohardjono, mayfield brooks, and Raha Behnam.

First, let’s situate.

I read in May a former CDC scientist say the U.S. had everything it needed for pandemic preparation. Leaders simply lacked imagination. They refused to learn from the past.

Here we are re-imagining our lives. The systems that weren’t built for our well-being are falling face down.

As I write, we pass the hundredth day of Black Lives Matter protests. Grief, power, rage, music, and dancing flood streets around the world as BLM blooms. Unjust murders by police continue. So do arrests of political prisoners. Fires burn California. And the air clears. Wildlife reappears as economic pause reduces pollution across the globe.

I’m not dancing this Spring, Summer — maybe not this Fall. But I’m getting more of what I need. Mutual aid networks, free food initiatives, and generosity naturally arise in my communities.

What are we capable of imagining?

In June, I asked Raha Behnam and mayfield brooks to sit down for a conversation on the “right now”. We circle virtually in July. We start in our bodies.

Reader, you may want to do the same. Place your fingers on the bones behind your earlobes to massage the vagus nerve and calm your fight or flight impulse. Cradle the back of your skull. Caress your throat.

Together, our stomachs stir. A sensation of a floating spine moves in. We laugh.

zavé: I’m grateful for time to think through some really big questions. The U.S. is in a pandemic racial-economic-health crisis. And racial justice movements are visible in the streets. Both interrelate with how U.S. empire continues to colonize its citizens. And we’re in three different places in North America, online together.

My first question is what are you dreaming of as artists amidst crisis, transformation, eruptions?

mayfield: I’m dreaming of wiping the slate clean. Putting an end to the confusion of ignorance and violence and untruths. How can we commune with truth?

Raha: I’m dreaming about people being on land and living. It’s not dramatic. We just live. That’s the revolution.

zavé: These are dreams about having agency—not scrambling for resources. What is your vision of community self-determination?

mayfield: I never thought that I would bike in protest with thousands of people on the Williamsburg Bridge.

I keep thinking about how connected the slavery abolitionist and prison industrial complex abolitionist movements are. The carceral state has infiltrated our lives and been normalized. What if we started an underground railroad of safe houses? What if there were ways to transport food from farms to the city on bikes?

Raha: Capitalism is a real jerk. There’s so much support in these protests. The Justice for George Floyd Instagram got folks being evicted connected to people who helped them occupy their homes. Having unemployment gave me time to support others.

zavé: The free food fridges in my neighborhood are a beautiful thing I never expected to see. For those of us getting pandemic unemployment, we have money beyond the basics.

mayfield: Money, wow. I applied in May, and when I looked at my account, I almost hit the floor. It’s like somebody gave me a $7,000 grant.

As artists, we can manifest money by pooling it. What if we created a trust fund for artists and activists without requiring applications? That approach towards money is what white artists do.

Raha: As people say in the streets, “Who takes care of us? We take care of ourselves.” We need to collectivize and think as an organism. We could take over plots and establish land trusts.

I don’t really want to go back to any semblance of what it was. I want us to continue paying attention to each other. This opportunity comes once in a lifetime.

mayfield: I’ve dreamt of being part of that land trust, raha. The land is helping us when we don’t even know, giving us life and sustenance. Honoring the space that we live in, this is the time.

zavé: I also think we’re in a rupture, a wound. We’re taking the time to look at it. It’s a lifelong practice to invest in self-generating resources. We don’t know what generations of activism seeded this moment. How do we sustain the work?

mayfield: The resources we bring are boundless. I forget that about the people around me and about myself. But that’s the kind of power available to us.

This is dreaming. Visioning. Remembering.

This is communicating. Building. Calling in. Demand.

Breaking free from the illusions.

This story circle is about freedom, well-being, and care as justice.

There’s something I can’t translate onto paper. I feel our sentences braid. I feel what can be.

We circle up again in August. That week, protests in Beirut around the explosion mount, and the Lebanese government resigns. Fires burn the Brazilian Amazon. The last intact Canadian Arctic ice shelf collapses.

zavé: How do we understand our work as integrated—performance, activism, farming, healing?

mayfield: I love farming because things grow at their own pace. Sometimes they don’t even sprout, they die.

My desire for my own labor is to have more time so that people leave me alone. I am tired of white people—really whitenNESS—wanting things from me.

Teaching today, I talked about the realm of survival as a realm of the beloved. Capitalism steals our knowledge of how to survive. What would it look like to work with the earth and the planet as a beloved space of being?

Raha: It’s so nice listening to you, mayfield—it’s moving me.

Recently, a group of young politicized Iranians began organizing material resources for Black Lives Matter. We loved being together so we continued to meet weekly. The labor I love to do for that group is hold space for us. To ask, “What is happening in your body, in my body?” Let’s stop distracting ourselves. Let’s not pretend we’re not uncomfortable.

zavé: Yes, labour is relationship-building. Labour is staying in the body. I’ve been asking, “How are we building movements? How are we collaborating as artists?”

I spent years in grueling political change work that silenced every queer person of color and Black woman colleague. How we feel labouring together is more important to me.

mayfield: The work of collectives is really powerful. New York is a hard place to do this. Here it’s more like there are groups—not collectives.

zavé: That’s a good distinction. What makes a collective?

Raha: It’s how decisions are made and leadership is distributed.

zavé: I want to work with other artists in an evolved relationship—differently from how choreographers have worked with me. What needs to decompose in our artist collaborations?

mayfield: I set environments and invite folks into a collective moment. I had a retreat in October where I was working with the framework of improvising while Black and doing this garden ritual. I invited Black artists I’d collaborated with to stay with me overnight and asked staff to leave the premises and provide food. I called it Black SleepOver.

Raha: Right! You say, “Here’s my proposal, I’m inviting you. These are my desires, this is the container.” When we’re clear about our desires and needs, others know what they have to work with.

mayfield: I love that the resource creates the container for us to share.

Raha: That’s beautiful. You can think of the whole world that way. zavé, I feel that way working with you. You invited Ube Halaya and I to collaborate with “We get to have an experience together.” I don’t think white supremacy culture works that way.

zavé: I find making work very lonely so I need to do it with others. I see other artists work, and I want to play. I am connecting more with my ancestral Indonesian temple dance where entire villages co-create and support it. I’m interested in that participation.

mayfield: Something about the village is really exciting. The pandemic is going to shift things. Maybe more cohesion will be possible and we’ll be able to create villages.

Raha: What makes a village?

mayfield: The dictionary says it’s a self-contained community with limited corporate powers.

zavé: Wow. What village would we create post-pandemic?

Raha: Once we make this village, we should write everything down to share with others creating their own villages.

zavé: The archive! How to learn from mistakes so we don’t have to recreate the mess? “Democracy” in the U.S. in 2020 is such a warbled response to pre-existing roadmaps.

mayfield: The Constitution was influenced by the Iroquois Nation—properly called the Haudenosaunee Confederacy meaning People of the long house.

Raha: And with the traumas of whiteness… Collision. You get America.

zavé: [Laughs] And then you get America.

Grounded in words of dream and purpose, I feel the support of unceded Lenapehoking—where I live and write. And the legacy of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, those that “made the house” in which nine nations came together as one.

I remember collective history to help seed our collective future.

zavé martohardjono is a performance and multimedia artist. They make works that contend with the political histories our bodies carry. Their arts and activism practices weave together political education, dance, healing, and community building to contribute to de-colonial and de-assimilationist projects. Both in and outside art spaces, zavé has led grassroots organizing and social justice advocacy for over a decade.

zavé’s writing has appeared in The Dancer Citizen, mxrs commons, HuffPost, and We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics. They have given talks at Brown University, Fordham University, Princeton University, University of the Arts, College Art Association Conference, Critical Mixed Race Studies Conference, and Movement Research.

As a performer, zavé has presented live works at the 92Y, The Kennedy Center, Bemis Center for Contemporary Art, BAAD!, Bronx Museum of the Arts, Boston Center for the Arts, Center for Performance Research, El Museo del Barrio, Gibney, HERE Arts, Issue Project Room, Storm King Art Center, the Wild Project, and elsewhere. Their performance work has been written about in the New York Times, Hyperallergic, Posture Magazine, and in the books Trans Exploits: Trans of Color Cultures and Technologies in Movement and Queering Contemporary Asian American Art.

Photo of zavé martohardjono by Nabil Vega.

Raha Behnam is an artist working across disciplines and practices towards liberatory modes of being and doing.

Photo of Raha Behnam by Amelia Golden.

mayfield brooks improvises while black, and is currently based in brooklyn, new york on lenapehoking land, the homeland of the lenape people. mayfield is a movement-based performance artist, vocalist, urban farmer, writer, and wanderer. they are currently an artist in residence at the center for performance research (cpr) and abrons arts center in new york city/lenapehoking. mayfield teaches and performs practices that arise from their life/art/movement work, improvising while black (iwb).

https://www.improvisingwhileblack.com/

Photo of mayfield brooks by David Gonsier.

Before her passing in October 2018, Black feminist writer Ntozake Shange—best known for her Obie-winning choreopoem, for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf—pulled notes together and penned an extensive love letter. She called it Dance We Do: A Poet Explores Black Dance, an acknowledgement of artists she felt privileged to have known as her dance instructors, colleagues and friends.

When histories of influential American dance of the 1960s and ‘70s are written, it is rare to find artists like Fred Benjamin, Dianne McIntyre, Ed Mock, Eleo Pomare or Mickey Davidson (the jazz dancer with whom Shange created another choreopoem, The love space demands) getting their due spotlight. Published last month by Beacon Press, Dance We Do is Shange’s personal contribution towards correcting the record and challenging the perception of Black dancing as a matter of natural ability rather than exacting technical craft and complexity.

In a section on Dianne McIntyre, the book surfaces names infrequently heard these days—Pepsi Bethel, Charles Moore, the extraordinary capoeirista Loremil Machado, lost to AIDS in 1994, and other artists I recall from my early days covering dance. Those names were spoken with reverence back then, but how many up-and-coming artists now recognize the contributions of these Black artists compared to what they might have learned about their white contemporaries?

Recovered from a series of strokes, Shange had set her mind to this and other long-dreamed projects, but she never completed the manuscript. Indeed, artists she still desired to interview—George Faison, Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, Bill T. Jones, Okwui Okpokwasili and the late Chuck Davis—do not appear in this volume of memories, profiles and informal conversations. But award-winning choreographer Camille A. Brown, who set the dancing for The Public Theater’s 2019 reprise of for colored girls, made it in as well as Davalois Fearon, renowned for her years with Stephen Petronio’s troupe and now developing a new career as a dancemaker. These artists extend Shange’s reach from the classic past into the future of Black innovation. That sense of heritage and continuity is crucial to her tribute to Black excellence in dance.

If what you’re looking for is scholarly analysis or substantive interviews, you’ll find Dance We Do to be an imperfect compilation. But Shange can be a vivid witness, sharing her experience of the colorful world of musician Sun Ra’s Afrofuturistic community, reporting on Fred Benjamin’s regimens and what she describes as ocelot-like moves. West Coast-based Raymond Sawyer—who counted beloved DanceAfrica founder, Chuck Davis, as one of his students—brought out the playful choreopoet in Shange. Check out this observation:

You would not recognize a short stocky young man as a dancer until he strode across the floor towards you and his legs became telephone poles or huge redwood trees. Raymond Sawyer floated across space as if he were a heron. His arms took on the character of cypress tree limbs, cutting through the air casually but with grandeur. There was something graceful about his movement. Elegant and African.

And this:

Amazingly, Raymond consistently made loud clicking sounds with his tongue that hovered over the drums, becoming the primary rhythm that we danced to. This clicking sound caused Raymond’s head to dart like a lizard or a snapping turtle. With an open chest always, Raymond propelled himself and the class to many movements based on the Horton or Dunham technique. We took to looking like we were straight from Lagos once we got started.

Passages like these add a dash of fun but remain frustratingly sketchy. One wishes Shange could have had more time to linger, to consider and flesh out the sketches. One wishes, overall, that she’d had more time, that we’d had more time with her.

Dear Gina,

I am a dance artist from Iran. I’ve been following your website and IG page for a good time. Still, I’m probably not considered as a member of your community since I’m not living in NYC. However, reading your letter I wanted to simply send you a sincere thank you letter.

I live in Iran where dance education is about zero. We don’t have any dance schools and dancing is prohibited in Iran. The COVID-19 was a disaster for many people (for me as well in many ways), but what I’m thankful for is the opportunity of taking part in your Spring drop-in classes. I was absolutely amazed that I am able to attend many classes without worrying about visa and travel costs, and I was able to meet many great artists and work with them closely.

Late at nights, while being at work, in our living room, or in my own small room, I attended classes offered by your organization while there was a generous option to attend it for free. Right now, Iran is experiencing a drastic economical crisis. We have the least valuable money in the world, and above that, due to sanctions against Iran we are not even able to transfer one dollar online.

I want to value the opportunity you provided for me to benefit from your wonderful resources. Browsing daily on your website to see what class is on today and trying my best to get to participate in that was a great joy of my quarantine time. I can’t thank you enough for that. I totally understand that this is a difficult time for everyone and you need to pay for your teachers and administration costs, but deep in my heart, I hope you are able to keep your plans for the same scheme, because you’re actually making an impact internationally at this time.

Sending my sincere appreciation and regards from Tehran,

Anonymous

Eva Yaa Asantewaa (pronouns: she/her) is Gibney’s Senior Director of Artist Development and Curation as well as Editorial Director for Imagining: A Gibney Journal. She won the 2017 Bessie Award for Outstanding Service to the Field of Dance as a veteran writer, curator and community educator. Since 1976, she has contributed writing on dance to Dance Magazine, The Village Voice, SoHo Weekly News, Gay City News, The Dance Enthusiast, Time Out New York and other publications and interviewed dance artists and advocates as host of two podcasts, Body and Soul and Serious Moonlight. She blogs on the arts, with dance as a specialty, for InfiniteBody.

Ms. Yaa Asantewaa joined the curatorial team for Danspace Project’s Platform 2016: Lost and Found and created the skeleton architecture, or the future of our worlds, an evening of group improvisation featuring 21 Black women and gender-nonconforming performers. Her cast was awarded a 2017 Bessie for Outstanding Performer. In 2018, Queer|Art named one of its awards in her honor, and Detroit-based choreographer Jennifer Harge won the first Eva Yaa Asantewaa Grant for Queer Women(+) Dance Artists. In 2019, Yaa Asantewaa was a recipient of a BAX Arts & Artists in Progress Award. She is a member of the Bessies Awards Steering Committee and the Dance/NYC Symposium Committee and the founder of Black Curators in Dance and Performance.

A native New Yorker of Black Caribbean heritage, Eva makes her home in the East Village with her wife, Deborah, and cat, Crystal.

Dani Cole, she/her, is a Lenapehoking-based (what is known today as NYC) Japanese-American movement artist, educator, writer, activist, and arts administrator. She founded the collective Mobilized Voices/MO B I V in 2018 and is a collaborator with jill sigman/thinkdance and ECHOensemble. Currently, Dani is the Curatorial Associate & Artist Coordinator at Gibney, and more recently, serves as the Editorial Associate for Imagining: A Gibney Journal with Editorial Director, Eva Yaa Asantewaa. Dani has traveled to South Africa to meet with fellow student activists in advocacy for the decolonization of education and has been an ambassador for the Foundation for Holocaust Education Projects since 2009.

Dani’s work centers body politics and the interdisciplinary. With the body as a three dimensional sphere — movement, text, and sonic vibration weave together into reflections on what was, what is now, and what is imagined in process. Navigating 15 years of dance training based on western white-supremacist, ableist thought — that the classical ballet and hypermobile body is the “Dance” body — Dani is in the process of dismantling her role in perpetuating self and systematic harm to her body and collaborator’s bodies. Access is her process, the language she is moving in and towards — listening, dimensional knowledge, trust. She is in the process of authoring her first poetry zine and is Gibney’s in-house writer, creating digital articles and interviews about presented and community artists.

In the past, Dani’s interdisciplinary works have been shared through the 92Y, TADA! Theater, Mana Contemporary, Actor’s Fund Arts Center, Bridge for Dance, Access Theatre, and the Emelin Theatre. Dani was part of the 92Y’s Dance Up! next generation of young choreographers. She has been commissioned by and held residencies at The Steffi Nossen School of Dance, Mana Contemporary, the San Francisco Conservatory of Dance, and Chen Dance Center.

Recently, Dani has shifted away from choreographic orientations to focus on facilitation, shared spaces with co-determination, and a focus on access in process — with her collaborators in M O B I V and the public. She is often teaching — embodied writing workshops, yoga for disabled and non-disabled bodies, and is an educator on guest faculty at various schools.

Photo of Dani Cole by Maria Baranova Suzuki.

DISCLAIMER: Opinions expressed in Imagining: A Gibney Journal are the writers’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views, strategies or opinions of Gibney.