Imagining

A Gibney Journal

Issue 4

Letter from the editor

Mirror? Door?

The Netflix documentary Pretend It’s A City, streaming since January, invites viewers on a spin around iconic Manhattan and the whip-smart mind of humor writer Fran Lebowitz. A friendly collaboration between Lebowitz and director Martin Scorsese, the film spotlights the kind of sardonic observations its subject is best known for—mainly, her endless, often relatable pet peeves. I found it more quietly absorbing and fascinating than LOL-ingly funny, though zingers do whiz in from out of nowhere. I’m a sucker for a good story, and Lebowitz has got ‘em (favorites: the one about the bus driver and the one about the bear guide).

But Lebowitz was on my mind for another reason as we prepared this, our fourth (wow!) issue of Imagining. In a revealing moment, Lebowitz wonders over the need that some readers might have to read—and read about—people like themselves.

We’ve all heard the “who look like me” or “who look like themselves” remarks almost too often. They can be an easy (too easy?) way to say, “I want to engage with people/be taught by teachers/watch dancers who are of my race, my ethnicity, my culture.” Most often, race. And there’s a very good reason for that desire—historical under-representation of people of the global majority, especially Black people, across many fields in a white-dominated society.

So, I was disappointed to hear Lebowitz dismiss the genuine need behind the use of phrases like “who look like me.”

“Now, people are saying, ‘There are no books about people like me; I don’t see myself in the books,’” she said early in the series’ final episode. “I always think a book is not supposed to be a mirror. It’s supposed to be a door. It never occurred to me to see myself in a book. Even as a child, it never occurred to me.”

That was a moment for which the expression “love-hate relationship” was made.

Unlike some of my friends, I’ve never been a Lebowitz fan. I do respect her mind. I do identify with her around certain things that get on her one last good nerve. Believe me, I do. But I don’t usually go out of my way to read or watch her. It took me a while to get around to watching Pretend It’s A City. Despite some real enjoyment, my ambivalence persisted.

Here’s the thing: books have always been doors for me, too. I certainly get it. I was a smart and curious kid who needed a larger world than the one my family, my family’s conservative, white-ruled religion, my elementary school, and the USA of my childhood, adolescence, and college years offered me. I needed to get out there with the Apollo astronauts and Star Trek and, years later, in there with Merlin Stone and Carl Gustav Jung. I did as much as I could, through television and reading, to expand my world and my possibilities within it.

At the same time, I chafe at the idea that we don’t need more books that act as mirrors, explaining us to ourselves and helping us feel less alone and better understood. Who’s to decide that? Someone who could find models for her future career almost anywhere she looked in white European and US literature?

One of the “mirrors” I picked up to read in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic was Saidiya Hartman’s Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (2007), a memoir of her time in Ghana seeking to understand and connect to the experience of Africans kidnapped or sold into slavery. I didn’t know I’d find a mirror in Hartman, decades after I first needed it when I visited Ghana, but I was so grateful for it. I didn’t even know I needed it.

Which is not to say a book must always be a comfort zone, a hiding place, a hall of mirrors in which to seal oneself off from everyone else. It can make it easier, instead, to realize and claim one’s place out in the world.

I came up in a time when music reflected my rich Black culture back to me (from Black and non-Black musicians) and opened up the cosmos, too. I also came into dance writing in the 1970s in a time of relative abundance at the heady intersection of dance traditions and genres; formal and informal venues; entertainment and radical experimentation. In that way, I had it all—the mirrors and the doors (and The Doors).

Imagining provides a platform for writers—some old hands and some exploring writing as a new venture and challenge—as well as a meeting place for readers needing the affirmation of many kinds of mirrors or the freedom of many kinds of doors. And, frankly, this is the fun of it. There’s so much to learn about ourselves as we also learn about others—in everybody’s growing awareness of what else is happening on the planet we’re lucky to share.

This month, Editorial Coordinator Monica Nyenkan and I take pride in bringing you work by theater director/choreographer Dan Safer (Witness Relocation), dancer-choreographer Jennifer Nugent, and cultural strategy consultant Durell Cooper. All three have something in common—being excellent educators and, in their own ways, both mirrors and doors.

Eva Yaa Asantewaa

Senior Director of Curation

Editorial Director, Imagining: A Gibney Journal

In the United States of Denial—one not limited by political party, race, ethnicity, gender, or sexual identity—the collision of systemic racism and the COVID-19 pandemic was inevitable. On May 25th, 2020, a white Minneapolis police officer knelt on George Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and forty-two seconds in a public lynching caught on video. The two pandemics crashed into each other. Infection rates and death rates spiked disproportionately in BIPOC communities—particularly in Black and LatinX communities. The quarantine’s economic impact fell most heavily on those communities as well. Almost overnight, phrases like systemic racism, anti-racism, and white fragility entered the common vernacular of news anchors and pundits describing the civil unrest. Corporations and non-profit organizations began releasing hollow “solidarity statements” supporting Black Lives Matter. Leading scholar Dr. Teri Watson calls this phenomenon “performative wokeness,” nothing more substantial than spectacle. Note: Dr. Teri Watson introduces the term “performative wokeness” in her essay, A seat at the table: examining the impact, ingenuity, and leadership practices of Black women and girls in PK-20 contexts.

To those on the frontlines of social justice movements for decades, though, none of this looked new. The chickens have come home to roost. The trauma of this country’s original sins—the kidnapping and enslavement of Africans, the genocide against Indigenous people of the Western Hemisphere—became epigenetic coding passed down through generations of Americans.

Merriam-Webster defines epigenetic as “relating to, being, or involving changes in gene function that do not involve changes in a DNA sequence.” Pioneering social science scholar Dr. Joy DeGruy identified inheritable genetic changes experienced among Black Americans as “Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome” in her book with the same name. The American atrocities previously mentioned—and far too many others to name—have traversed generations, haunting the amniotic fluid of the Black womb and the semen of the Black man, shaping the Black body. Before we have a name, we have trauma.

Our healing is complicated as we are retraumatized, daily, by news stories and images, spaces we enter, monuments we are forced to see, and, of course, oppressive policies and procedures that control our lives. While I don’t have all the answers, I know that our healing must happen individually and collectively.

The journey to healing starts with the self. World-renowned racial trauma therapist Resmaa Menakem—author of My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending our Hearts and Bodies—has developed a healing approach called “somatic abolition.” The word “somatic” derives from “soma,” relating to the body. “Abolition” refers to the act of abolishing a system, practice, or institution, calling to mind Harriet Tubman and her Underground Railroad that liberated countless enslaved Black people. Thus, somatic abolitionism as a healing modality for Black bodies de-centers the supremacy of white bodies and aligns ancestral wisdom with physical release.

The blood of our ancestors compels us to heal; we are “duty-bound,” as my friend and colleague Toya Lillard, Executive Director of viBeTheater Experience, often reminds us. While this generation deals with the daily slaughter of Black lives, we have the responsibility to heal. In somatic abolition, we might even find that the pathway towards liberation is, in itself, a source of joy. Then, what might liberation look like? And is it liberation away from something or towards something? We must ask these questions to avoid the common pitfall of reverting to the service of white male patriarchy and white body supremacy as we seek inclusion in a broken system.

As I write these words, the Federal Drug Administration has approved COVID-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna, and global distribution has begun. But there’s no vaccine for age-old systemic racism. How long must we endure the plague of structural oppression? How will we know we are on the path towards healing? Perhaps our ancestors will guide us. Perhaps joy is the answer. Perhaps radical love is the answer. Perhaps our mere existence as Black bodies, against all seemingly insurmountable odds, is the ultimate show of resistance.

As Celie cries in Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, “I’m poor, Black; I may even be ugly. But dear God! I’m here! I’m here!” I hope for more than just the survival of our current traumatic conditions. I hope for my people’s surthrival in an Afro-future where healing is our birthright. Our minds, hearts, souls, and creativity, gifted to us by our ancestors, are the vaccines we’ve been waiting for.

Durell Cooper is a leading cultural strategist and the Founder/CEO of Cultural Innovation Group, LLC; a boutique consulting agency specializing in systemic change and collaborative thought leadership. He is also the creator and host of the web series, Flow. He is an adjunct instructor at the City College of New York where he teaches Arts Education in Urban Settings. He’s a former Program Officer at the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs (DCLA). Prior to joining DCLA, he worked at Lincoln Center Education on multiple social impact projects. Durell graduated from the Impact Program for Arts Leaders (IPAL) at Stanford University in 2008. Currently, he is pursuing his doctorate at New York University.

Photo of Durell Cooper by Alejandro Garcia

In March 2020, the online teaching platform freeskewl was founded to provide ongoing classes and events as the COVID-19 pandemic forced many dance spaces and platforms to temporarily close their doors. During my first online class, I stood up and moved away from the screen. I felt so alone.

In this strange year, moving more slowly, I see my interests in teaching shifting. Perhaps it is my living space—and watching each of you dancing in yours—that determines my thoughts these days. I don’t want to go back to the studio.

That is not completely true, of course. I do want to be back in the studio. But I am afraid of what it will mean to return, what might be left behind, what part of ourselves will be left behind.

As we attend our various dance classes at home, with our stuff all around us, the readiness for dancing is an extension of our home. We experience living space and dance space as one. How, then, do we transport our exquisite domesticity to the studio?

I can see myself trying to squeeze into habit, into rigorous class offerings, alone in my apartment. Our togetherness builds the heart, the heat, the passion, perhaps. It is our togetherness that guides the class, that affords me what to teach. So while alone, teaching shifts to allow the transmission to flow between us.

Inside this online class’s creative container, I feel emergent and rejuvenated as I share my dancing within states of unknowing, relearning, and deep listening. While teaching, I struggle, wondering what to teach, or more so, how to teach and why? I feel productive, humility, and love for dance, my peers, my mentors, my family, and so much love for all of us as students.

Am I preparing myself to return to the studio?

***

With freeskewl’s support, I initiated pedagogy/poetic entry, a monthly series featuring teaching artists who share their pedagogical practice and thought, followed by a discussion. Within the series of talks, we collectively mine for new and/or re-imagined teaching methods, research, and rhetoric.

For me, the physical dance space must be safely supported by responsive conditions of care. I want the studio to be a space that exceeds itself, where the dance class becomes personal practice, a place to encounter each other, build physical structures for empathy. Where we understand movement and dancing desires cellularly, theoretically, and humanly. What seems to continue to land as important is the experiencing, the attuned awareness and prioritization of perception, proprioception, and the unfolding of how we perceive ourselves in motion. How many ways can I teach experiencing while acknowledging that presentation and words reverberate, resonate, and resurge. As soulful, feeling humans, we have the possibilities to transcend and speak with complexity.

Opening to the periphery, reaching out and returning home with breath, thought, then action. Inflating and deflating into the floor, back up through you. Accessing all the senses, just one, which entry point resonates or reveals a surge of connectivity that affords a kind of full expression from interior to exterior, asking which way do I go from here? Inside a felt, intuitive space, I think the practice of yielding and listening invites inquiries that reveal to us that which continues to remain—its effects and also its abundance.

***

Seeking feedback from my teaching practices, I increase transparency, continuously dilating my practices to better reveal habits, fears, successes. I thereby attempt to disrupt embedded patterns of unquestioned truths and beliefs that assume what dancing is. My movement stems from love and from remembering touch, articulating my curiosities, allowing the vibrations that surface in my teaching and performing to reverberate back into each other.

Attention is teaching me

Form is there

How do we push past it

Live alongside it with the use of attention

Invite other attentions that move the form

into modes that

Define Describe Identify Bend Queer

Inside form while disidentifying with form itself

(Un) habiting the dance

I also walk into a dancing space, covered with dancerly insecurities, violent self-talk, and the yearning to accomplish techniques that aim to be right. I have to question what I am bringing into the dance room. Are anecdotal practices enough? Narrating and sharing my own dance story at the moment, inviting others to share in or experience this. Through imagery and music, developing the class time together, finding a way in and through codified forms, shape, and gesture. As I prioritize problem-solving, the process of finding connections between movements develops a logic that makes sense and is felt. The dance does not only happen once we have figured out how to dance.

I want to encourage students to hear ideas and prompts but question them, make them their own. I am hoping to employ exchange and conversation. Having always taught intuitively, it seems important to present that opportunity in the class plan.

Am I teaching the very inclusive and decolonizing, the very anti-racist, queer affirming, and feminist practices I have been reaching towards?

I know the possible implications of my whiteness, the consequences of my white fragility. The choice to be disorientated finds me tumbling, failing, relearning, and unlearning when teaching within the disorientation of my privilege, as opposed to being oriented to it.

Feeling myself stumble through the process of writing, moving back and forth, editing up to the last moment, I cannot stop the vulnerability of landing somewhere in words knowing that I am just touching down. How do intentions leave my consciousness and activate into words? How do words leave the page and activate inside the class space?

***

Sending water to the ear hydrates the pathways that lead to it, providing support and wakened perception around it. The water is in constant motion, attending to the areas of less pressure and providing weight. Pooled weight brings attention. Attention can allow for care shifts and redirect tendency. Not completely soft nor surrendering but sending tension as forceful boldness and care. Pressure that is supported and sent throughout the mass body. There is a release as it carries out, and I think we can feel each other’s release, each other’s emotion through listening even–and especially–when it is hard to stay present. Caring for the whole being the whole collective as an entirety increases abilities to understand range/growth and collective consciousness.

So it is processual, like the dance class; this type of learning and experiencing can mobilize itself forever. Notice how I feel and move slowly with the listening—rebirthing daily into a shifting aliveness.

***

Standing, noticing the floor, feet yielding, asking to be in relationship with the floor; an energetic line moving up two legs through the center of the pelvis, the pubic halves. Curious tailbone, softening the circumference of the tailbone; revealing its action while seeing, smelling, doing, reaching. Acknowledging the aliveness of bones, what do they look like breathing, and how is the marrow flowing? How are we flowing?

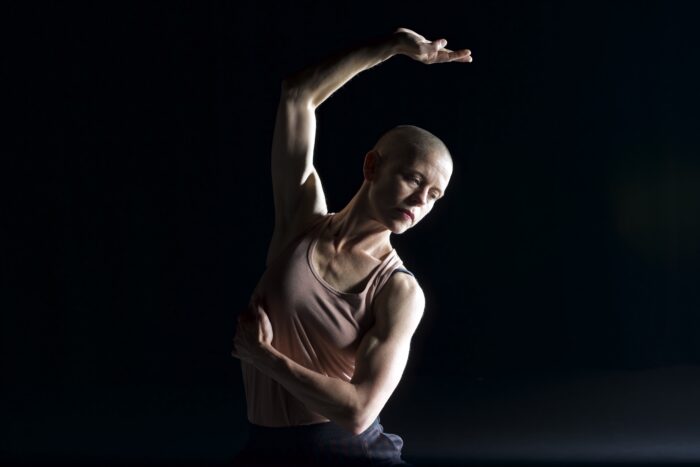

Jennifer Nugent is originally from Hollywood, Florida, and has been living and working in New York City since 1998. Her practices are profoundly inspired by Daniel Lepkoff, Wendell Beavers, Patty Townsend, Thomas F. DeFrantz, and Paul Matteson. Through performing and teaching she aims to nurture the proposition of physicality as a theoretical and complex language that resides inside a rejuvenating container of possibility. Jennifer continues to augment these practices through sharing and refining ideas in front of others—a transmission of spoken and gestural language.

Since living in NYC Jennifer has performed most notably with Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company (NYC 2009-2014), Paul Matteson (NYC 2002-2020), David Dorfman Dance from (NYC 1999-2007), and Martha Clarke (NYC 2007-2008). She is currently a teaching artist at Gibney Dance (NYC), Sarah Lawrence College, (NY), and the virtual platform freeskewl where she hosts a monthly series called Pedagogy/Poetic Entry.

Photo of Jennifer Nugent by Jim Coleman

1.Bury your face in a cat and breathe in (not good if you are allergic to cats).

2. Throw a ball with a dog.

3. Learn to cook something new. I learned how to make a vegan lasagna, and it rocks.

4. Call your parents, especially if that’s not something you usually do a lot. I’m not in touch with mine as often as I could or should be, and I realize that if they get this thing, that could be it, so I want them to know I love them.

5. Clean where you live. Clean something every day. At the very least, straighten up the couch.

6. Dance to “Bam Bam” by Sister Nancy.

7. Look at the sky.

8. Touch a tree or plant.

9. A trick when someone is in a state of panic is to ask them to help someone else. Offer to help someone else with something.

10. Watch an old episode of Pee Wee’s Playhouse.

11. If you can, splurge on a nice soap or body wash. Sometimes self-care is a bold and revolutionary act, but it is hard to remember to do or make time for.

12. Learn how to repair something you would otherwise throw away.

13. Understand this: THE DUCK JUST WANTS SOME INTERACTION AND TO FEEL CONNECTED. This will make sense later.

I wanted to write about Joy. About making work at this moment, on the planet, about how I could personally address what is happening in the best way possible. I thought about making a list of 100 Things That Can Give Joy, so that my essay was practical, so that it could offer something to you.

(and I do mean you. We are so divided right now by space and masks and spraying droplets and quarantines, so you and I are about as connected as anybody is right now. I’ve been thinking about connective tissue and conduits of exchange. These words are a tunnel through which things I’m thinking about can reach you, so it’s a connection.

It’s also time travel. I’m sitting in a barn in upstate New York writing this, and you’re reading it at some point in the future, but when you read this, at THIS MOMENT for you right now, I’m in the past. This all sounds very stoned, I know, but this pandemic has afforded time for contemplation, and some of these ridiculous thoughts make me happy).

14. Reach out to someone from the past and let them know you have love for them

15. Buy coffee for the person behind you in line (if you’re somewhere with a line).

16. Just let yourself cry if that’s how you feel.

I wish I had expertise to offer or advice. I’m not so eloquent, so how about this?

“Don’t wait until you have no more suffering before allowing yourself to be happy.”

That’s not me. That’s Thich Nhat Hanh, but it makes so much sense. Note: Hanh’s quote appears in his book, Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation.

I don’t suspect everything will ever be all okay. So, maybe try to be happy while we can, when we can?

(All of this is aspirational for me. I don’t speak from a place of having figured much out).

I’m trying to make work from this place now. Of recognizing the current situation and speaking to it and from it. And looking for ways I can help out.

Maybe something I can do is try to make work that imagines the world I want to live in, as well as shining a light on the world that is. I’ve always thought it heroic for us, as makers of things, to go to the dark places, to plumb the depths, to jump headlong into the abyss. But, Holy Shit, every single day, these days, feels like the dark places, the depths, the abyss. Maybe it is heroic to stack things up so that the people around us might scale the heights.

It makes me think about medication. Sometimes you just need an antidepressant so you can have the feeling of waking up without massive dread one morning, so you can realize OH, IT IS POSSIBLE TO NOT WAKE UP WITH MASSIVE DREAD. And then you can try to move your life in that direction. I don’t mean to oversimplify things, or to make it sound easy. I think it is one of the most difficult things, but probably so worth it.

So how does all this pull together?

17. Try to do something you don’t know how to do.

18. Maybe even do something you’re scared of.

That’s me writing this. I haven’t written an essay since maybe the first year of college, so in about thirty years. I have written some rather long Facebook posts in the past few years. That is as close as I have come.

I’d like to think of writing this as part of my goal of Making Work That Inspires Joy.

A duck walks into a bar and waddles up to the bartender. The bartender looks at the duck and says “May I help you?”

“Got any grapes?” says the duck.

“No, we don’t have any grapes,” replies the bartender.

So the duck leaves. The next day, the duck waddles into the bar and goes up to the bartender.

“Yeah?” asks the bartender.

“Got any grapes?”

“No, we don’t have any grapes! Get out of here!”

The duck leaves. Third day in a row, the duck waddles into the bar, looks at the bartender, and asks:

“Got any grapes?”

“NO, WE DONT HAVE ANY FUCKING GRAPES. IF YOU COME IN HERE ONE MORE TIME AND ASK IF WE HAVE ANY FUCKING GRAPES I’M GOING TO NAIL YOUR FUCKING HEAD TO THE BAR!”

The duck leaves.

Fourth day in a row, the duck waddles into the bar and goes right up to the bartender, and asks:

“You got any nails?”

“What? No!”, the bartender says.

“Good. Got any grapes?”

(see item #13 from above).

Dan Safer is the Artistic Director of Witness Relocation. He has directed/choreographed all of their shows—ranging from fully scripted plays to original dance/theater pieces to many things in between all over the place; from the backrooms of bars in NYC to Théâtre National de Chaillot in Paris. Dan has collaborated extensively with playwright Chuck Mee, and WR was one of the first companies to do a Toshiki Okada play in English in the US (Five Days In March, at La Mama). His work as a choreographer has been at BAM, DTW, Danspace, Ash Lawn Opera, and many other places. In 2011, he choreographed Stravinsky’s RITE OF SPRING for Philadelphia Orchestra with Obie-winners Ridge Theater. Artforum Magazine called him “pure expressionistic danger,” and Time Out NY called him “a purveyor of lo-fi mayhem.” Currently, he is on faculty at MIT, after nearly two decades teaching at NYU. He got kicked out of high school for a year, used to be a go-go dancer, and once choreographed the Queen of Thailand’s Birthday Party.

Photo of Dan Safer by Maria Baranova

Eva Yaa Asantewaa (pronouns: she/her) is Gibney’s Senior Director of Curation as well as Editorial Director for Imagining: A Gibney Journal. She won the 2017 Bessie Award for Outstanding Service to the Field of Dance as a veteran writer, curator and community educator. Since 1976, she has contributed writing on dance to Dance Magazine, The Village Voice, SoHo Weekly News, Gay City News, The Dance Enthusiast, Time Out New York and other publications and interviewed dance artists and advocates as host of two podcasts, Body and Soul and Serious Moonlight. She blogs on the arts, with dance as a specialty, for InfiniteBody.

Ms. Yaa Asantewaa joined the curatorial team for Danspace Project’s Platform 2016: Lost and Found and created the skeleton architecture, or the future of our worlds, an evening of group improvisation featuring 21 Black women and gender-nonconforming performers. Her cast was awarded a 2017 Bessie for Outstanding Performer. In 2018, Queer|Art named one of its awards in her honor, and Detroit-based choreographer Jennifer Harge won the first Eva Yaa Asantewaa Grant for Queer Women(+) Dance Artists. In 2019, Yaa Asantewaa was a recipient of a BAX Arts & Artists in Progress Award. She is a member of the Dance/NYC Symposium Committee and the founder of Black Curators in Dance and Performance.

A native New Yorker of Black Caribbean heritage, Eva makes her home in the East Village with her wife, Deborah. Sadly, their best-cat-ever Crystal traveled over the Rainbow Bridge on February 18, 2021.

Monica Nyenkan is a Black queer community organizer and arts administrator hailing from Charlotte, NC. She graduated from Marymount Manhattan College, with a Bachelors in Interdisciplinary Studies. Currently based in Brooklyn, NY, her artistic and administrative work focuses on creating equitable solutions with and for historically marginalized communities in order to make art more accessible. In her free time, Monica loves to watch horror films and share meals with her friends and family. A fan of educator and historian Robin Kelley, Monica firmly believes the decolonization of our imaginations will help facilitate a more radical and inclusive way of living.

Photo of Monica Nyenkan by Jakob Tillman

DISCLAIMER: Opinions expressed in Imagining: A Gibney Journal are the writers’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views, strategies or opinions of Gibney.