Imagining

A Gibney Journal

Issue 5

Letter from the editor

As I’m writing this intro, it’s still early March. The weather has started to warm up. A singer friend writes from LA, excited to tell me that birds have been singing for her, gloriously, every morning. My heart longs for a subway ride to those city places that embrace nature and, therefore, embrace me. More than traveling, more than watching live dance, cheek by jowl with spectators breathing in and out on either side of me, I miss my birds.

It comes to me in a flash! That’s what I’m going to do, as soon as I safely can. I’m going to hop on a train and go find my birds.

As I’m writing this, in March, COVID vaccination has picked up in the city. As a senior, I’ve now had both of my doses. There’s steady talk of more and more re-openings–schools, movie theaters, indoor dining. The CDC says, if you and your friends and family have completed your vaccinations, feel free to get together indoors, close-up, maskless. Yet the spread of COVID variants here, as elsewhere, raises many as yet unanswered questions–first and foremost, are any of these variants wily enough to evade the vaccines we have now? Do we even have a clue?

Which is to say, we tend to avoid complexity and reach for simplicity–the easy way out–at our potential peril.

Lately, I’ve been listening to people grapple with the unavoidable complexity of language. Questioning the widespread use of institutional solidarity statements and land acknowledgments that seem to fall silent before they get to the good part–the part about what the heck you’re willing to do to set things right. Questioning how some non-Indigenous people assume they can say they’re living on a particular nation’s land when, actually, the jury’s still out on which Indigenous nation’s land it really is. Questioning how a speaker or writer can refer to diverse people grouped together without privileging one racial, ethnic or cultural group over another or misnaming or erasing whole groups altogether.

”I am a Latina,” one arts leader complained. “Not Latinx! Latina! I’m not giving that up!” Femme–which had a particular and glamorously embattled meaning when I was a much-younger lesbian–now seems to have shapeshifted while I wasn’t looking. (Wait. What?) So, I get it.

As a writer and editor, my trade is in language. So, I can’t sidestep any of these questions or conflicts…or opportunities. I work for an organization where, as recently happened, I can now raise these complex issues, get a good hearing and find people willing to do the diligent work they require, making the effort to keep one another sharp and responsive. Which is not to say we’re always going to get things right–or get them right away.

But part of what keeps me going is the belief that books can be a force for good in the world. They can open up new ways of thinking and understanding; they can give us new perspectives on our own lives and experiences.

In his superb essay for this issue, “Witnessing the Blues,” Max S. Gordon writes, “I need you to know the truth of these times; I need you to know who I am.”

That’s a call for acknowledgment and respect as a baseline from which right action and right relationship can follow.

We all have specific stories grounded in who we are, what gifts we bring and how the world has allowed us to move through it. Let’s be excited about learning who we all are and welcome as many histories, gifts and birdsongs as possible.

Along with Gordon, I welcome unique, amazing voices to this month’s Imagining. They include Krishna Washburn–blind dancer and force behind Dark Room Ballet; Kai Hazelwood–former ballet dancer and co-founder of the anti-racism training program, Practice Progress; Alyssa Gregory, working to raise the strength and self-determination of Chicago’s dancers; and New York dance artist Marielis Garcia who shares the struggles of her Dominican immigrant family inside the “limbo” of the United States. Garcia reminds us that it’s the chorus of all our voices that gives us our true chance at greatness.

Eva Yaa Asantewaa

Senior Director of Curation

Editorial Director

*When I refer to America and Americanos in this essay, I am referring to a United States of America context and not the entire Las Americas.

I don’t have a clear history.

“Asegurate que no pierda tu papeles.” “Be sure not to lose your papers” is something my mom used to say about preservation in the United States; a way to prove I was born here– my social security card. That weird beige and blue card that has my 13-year-old signature on it, that card is my papers. That card is proof that I am from here.

I am a 35-year-old woman, and I get nervous EVERYTIME I go through customs. “No need to be nervous. Where will they send you?” asks my supportive, white, cis-male lover, and in all earnesty I can only mutter “Limbo.”

I think less about where they will send me in this situation, though we know that would mean cages. There are currently children in cages in the good’ol USofA. What I really worry about in a situation where my papers might not be enough proof of my Americana-ness, is being put into limbo.

What is Americana-ness? What are American customs? Do Americanós know? It seems so obvious that when arriving at a place one might be introduced to the customs of that place. The customs provide the visitor with the ability to move in and around that place with a sense of context and reference. American customs are not about generosity of context; American customs are about each (white)man for himself. (We have learned that American history is not about context and more about whitewashing.)

A few washed American customs…

Thanksgiving. In essence; yes, more gratitude is always a good thing, but the “peaceful dinner between pilgrims and Indians” that is taught to every American elementary school student has led to a custom of disregarding America’s complex history of thievery, deception and murder. (Indigenous, Native American communities have suffered disproportionately in the global pandemic but are left out of national statistics, American customs 2021.)

Puritanism. Don’t talk about nipples. Don’t even look at nipples. Boys will be boys. Girls should sit with their legs closed, unless they want to be grabbed by the pussy. And yes old white men who can’t even say “menstruation”, will keep control of women and their bodies. (ICE was performing unconsented “surgeries” on women in their facilities, American Customs 2021.)

Bootstraps. What are bootstraps anyway? Working hard in the pursuit of your happiness, is a great approach to life, yes, but the “hard” of that work should not be determined by the money of your ancestors, or better yet, the “hard” of that work should not be determined by where you come from. “Pull yourself up by your bootstraps” perpetuates the American custom of ignoring the labor of the bodies that make someone else’s profit. (“Undocumented” immigrants are performing essential jobs securing the United State’s food supply during a pandemic but they have no health, monetary or legal protections, American Customs 2021.)

I was talking about limbo… If you have limited resources and are unconnected [no $$$$], being put into limbo means someone/something else controls time and space. Autonomy lost to the whims of another’s power. Limbo, like the game, causes the player to bend over backward, just to take one foot forward.

I was raised in the space between limbo and liminal.

My upbringing is a collection of being Dominican, American, Black, White, and of no clear ancestral tree. Liminal is something I have felt my entire life. Everyday. In every place. A bit of this. A bit of that. For me, the liminal is my family’s celebrations of two independence days, and me feeling no kinship for either country. Liminal is a place of nowhere– and everywhere– at the same time. Existing in the liminal can be at once performance and authenticity.

But limbo was always around. It was my alcoholic aunt who always peed on herself at parties. It was Biembo, the man who had no clear familial relationship to us. He drifted in and out of our lives, always welcome if he didn’t show up high. My uncles, the livery Taxi drivers who worked for tips. There was always adult talk of buying items on layaway, and getting a better job than ‘la factoria,’ and so many diligencias about things I didn’t understand. Always, there was “vamo a ver,” because “we’ll see,” is the best you can do when a promise can’t be made.

Limbo is the promise-less land.

When my mom came to America at age 12, she almost immediately started working in a factory. (Because of her “hard” work, and credit debt: my mom is the epitome of the American dream. She (and my dad) worked multiple jobs to be sure they could pay all the bills and feed their family (including and beyond me and my siblings). My mom is Americana y Dominicana but she (and many like her, including my dad) know first hand the displacement of limbo. Leaving important things like agency and autonomy behind, because when someone/something controls your time and space, things like agency and autonomy can get you in trouble.

When I was a young girl, my mom would look at me and claim my Americana-ness both proudly and with subtle disdain. To her, Americanas wear their shorts too short, they are loose and they talk way too much. I am very much an Americana: my shorts are short, I avoid bras as much as possible, and I believe my pursuit of happiness is a birthright. I also drop my s-es when I speak spanish. Soy Americana y Dominicana. Liminal.

In liminal-ness, the agency is not futile despite it seeming so.

I think it’s important to note that power is necessary for support, growth, and evolution; but so often power is abused, or it is misunderstood as a tool for control. If someone feels power by controlling someone else’s time and space – they too are most likely being controlled.

Is it worse to be unconscious in the ways we perpetuate the control of other’s time and space, or to do it because that’s the way the man says it’s done? It is through a benumbed approach to leadership that causes many people to play into the power dynamics of placing others in limbo.

Being in a position of power really requires an ego-lessness, self-awareness–a willingness to adapt, a malleability. How can we, as American people transform and transcend the ego-money-driven democracy that was built to work this way and create a new set of power dynamics?

Side note, but in relation to ego/power: I am thinking about the ways ego and power dynamics have affected me as a dancer and what I have observed in our field. How often as a dancer have you been placed in limbo: waiting for details on that contract, your labor ignored or unacknowledged, delays in payment, transparency lost because you aren’t deemed important enough for information to be shared with?

I am in awe and admiration of the work Dance Artist’s National Collective has done and continues to do to empower freelancers to collectively consider the ways we can organize to develop safe, equitable and sustainable working conditions. If we continue to approach our careers with “hunger” then we perpetuate the idea that there is not enough; placing ourselves and others in limbo.

Ay ombé.

It gets complicated quickly and it does not have to be. Many Americans believe socialism is a bad word, and that caring for others—anyone different from you—is a sign of weakness; we have arrived to American Customs, and it’s time for adaptation.

The liminal exists as an experience, a way of moving through the world—undefined, but obvious to anyone who experiences it. The liminal is a way of finding and defining one’s fluid and adaptable understanding of individual identity.

Limbo is objectification. Limbo is someone else’s definition of identity, capacity and “rights” supplanted onto others without care, equity, or exchange.

To be put into limbo means: losing history para conseguir papeles— exactly what my parents have done for me. I should know better. I should walk through customs like a proud Americana. I should brand that passport like a gold watch given to an employee after 35 years of good service– instead of actually giving them a sizable raise. That gold watch is as American as my blue passport. So American.

Sadly, I’ve seen people put into limbo. I grew up watching people do this dance. Limbo is having your time and space directly controlled by something/someone else.

Being Americana, I know I have a voice. I believe in individuality and, though America is a mess, I believe we have the potential to be great as defined by ALL the people who live here and work hard here. Great as defined by all our voices. Our interests. Our pursuit of happiness, both independently and together.

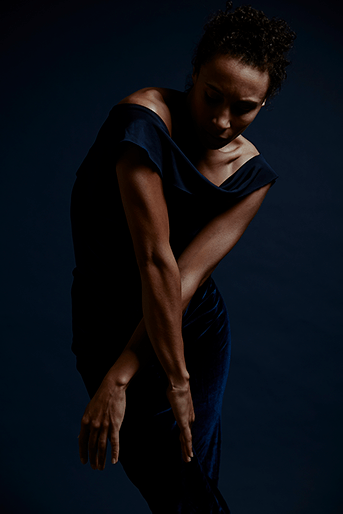

Native New Yorker and Dominican American dancer, choreographer and educator Marielis Garcia holds a BFA in Dance, and an MFA in Digital and Interdisciplinary Art Practice. Marielis is currently an Artist in Residence at University of Maryland, School of Theater Dance and Performance Studies, and is developing a work for Alvin Ailey/Fordham School as part of the New Directions Choreography Lab. She was UNCSA Choreographic Fellow in 2017 and has taught classes for Rutgers University and University of North Carolina Greensboro. Marielis produces collaborative works through MG DanceArts, which has been presented at Aaron Davis Hall and Judson Memorial Church, among others. Possibilities of Dialogue, her ongoing collaboration with David Norsworthy, was awarded Kaatsbaan and Dance Initiative residencies and debuted at Toronto’s North York Arts Center in 2019. Marielis has danced with Brian Brooks, Stefanie Batten Bland, Peter Kyle, and Helen Simoneau and frequently collaborates with visual artist Madeline Hollander.

Photo of Marielis Garcia by Whitney Browne

“I got the key to the highway,

Billed out and bound to go

I’m gonna leave here running

Because walking is most too slow…” – Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee

1

In 2015, my brother-in-law married a woman from Cartagena, Colombia. During the wedding ceremony, the guests stood in a large circle while the bride’s sister performed a dance in a flowing white dress, her hair worn in an Afro with a wreath of wildflowers.

I see her, even now, traveling through the space, her brown arms lifted–free, exuberant and inviting, while her feet took measured, careful steps, barely moving at all. I was touched by her dance, the celebration in every gesture. Shoulders hitched, hands on hips, she was, by turns, sassy, rapturous and very much alive. I was later told that the dance she performed originated in slavery. Her arms rejoiced because her legs could not. When the dance was originally performed hundreds of years ago, the dancer’s feet had been shackled, bound with chains.

It is conceivable that her movement may also have been constricted by overwork, exhaustion or the mutilation of her feet for attempts to escape. That dancer, in another time and place, her body the property of someone else, could not move her body freely. Yet the dance I watched was free.

Her movement seemed to affirm: whatever you do to my body, even if you torture me and sell my children, you will never control my access to joy. And I’ll tell you, because it is still true all these years later: the paradox of that understanding–that dancers, when inspired, when fully released, can find beauty in the dance, not despite evil and cruelty, but as a way to witness it and ultimately transcend it– broke me all the way down.

There are so many rich examples of witnessing to be found in Black literature, dance and song. But I don’t know if I have ever personally experienced a more compelling metaphor for the Black artist’s imperative than the dance I saw that day, nor a more definite appreciation of the blues, why we have a responsibility to engage with it, to reveal it to others.

My work as a writer is guided by two coordinates: witnessing and the blues. The blues in the Black imagination is a traveling, roaming thing. The Black body in America is always in movement. Wanting to be free and finding our home are part of our archetypal story since we came to these shores. If you are a writer, you write it down. If you are a dancer, you walk it around. Singers witness through sound.

On a daily basis, the Black artist–because it is also true of the Black American–is invited to be complicit in his or her own annihilation. And if she is queer or female or transgender, this dynamic is even more pronounced. In a country where her oppression relies on her story’s being misunderstood, mythologized or dismissed, she knows she must remain true to the blues in her work. The Black artist who lies wastes everyone’s time.

And it’s very tempting to lie these days. We live in a time of great liars and political whores. Past traumas are revived daily as we watch the abuse and neglect of those in our society who are most vulnerable. Sociopathology is rampant. The most basic definition of evil: using your creative power to destroy another person’s ability to create. We have gone so deep into capitalist greed that some of us will never be satisfied until the Black body cannot vote, cannot make a decent wage, has no access to proper education or health care, and, too exhausted to dream, can only work, making someone else richer–a return to slavery.

In 2021, I know that I am not legally a slave, but I am also aware, in ways that can’t exactly be defined, that I am enslaved. I try to create, and sometimes succeed, but too much of my power is spent on negotiating rage, on resisting addictions, and on psychological survival. America is obsessed with racism, often fetishizes it, but seems, in the end, perversely unwilling to change it. It is very tempting to stay in a state of dissociation, to want to leave or even harm one’s body. How do you engage the spirit when the body is in chains? At the time of this writing, with more than half a million Americans dead from Covid-19, we are witnessing unimaginable violations. We need inspiration. We need help.

When society betrays the body, the dancer and the dance become more vital than ever. She reminds us why the body is sacred, why poetry and compassion matter. Her body becomes a canvas, she is a witness to pain. The Black artist knows exactly what we’re capable of because her life and her children’s lives depend on that knowledge; she may know us better than we know ourselves.

Playwright and poet, Ntozake Shange wrote in her extended choreopoem, for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf, first performed in 1974:

the melody-less-ness of her dance

don’t tell nobody don’t tell a soul

she’s dancin on beer cans & shingles

this must be the spook house.

Musician Nona Hendryx answered her a year later in the Labelle song; “Phoenix: The Amazing Flight of the Lone Star”:

Dance the blues.

See how she dances to bring us the news.

She how she dances, ashes and news.

She how she dances, rise from the blues.

If the dance is powerful enough, the dancer breaks through our collective trance, rouses us from our perpetual numbness, and leads us to liberation. Using her creativity as a guide, she returns us to deep places of possibility and wonder.

2

I am not a professional dancer, although, in one way or another, I have danced all my life. My first conscious memory of dance, as I’ve shared in other writing, was dancing with my grandmother in Cincinnati, Ohio. I could barely walk, still in Pampers, but I’d hold the edge of a chair and bounce while she, in her pink bathrobe, would dance to our favorite artist: Al Green singing “(Here I Am) Come and Take Me.”

I couldn’t have known then why I responded to that song, but something about it encapsulates the blues for me, the deep sadness and yearning in Green’s performance, mixed with sensuousness and vulnerability. I also remember that we played Al Green after my grandfather’s funeral, and we danced. My family taught me in those years that the blues isn’t just a musical genre, it’s a functioning tool for survival. Just as a carpenter uses a hammer to smash through a wall, the blues can be used to break down grief. I learned from my family the importance of dance as a witness to experience. Dancing our blues restored our faith in each other, led us back to joy.

As a writer, I am aware what a powerful story can do, but I also believe that there is a certain aspect of the Black experience that can be achieved only through dance. Dance offers a particularly compelling testimony, a body-memory that precedes language. You may lose your language, but memory stays in the bones. When you choose to use your whole body to create, you invite a different relationship to pain.

Dancing, the kind that transforms, requires the audacity to take up space. Not all of us feel we are allowed to take up space. Dancing is predicated on the fundamental presumption that your body belongs to you. Dancing is agency in motion.

Dancing is deliberate. No one dances by accident. Anything done deliberately has the potential to be punished. There is an inherent rebellion in dance. Some of us have been punished for dancing.

Dancing is witchcraft. It stirs shit up. Dancing is also practical. If you can tap your foot, you can dance in a jail cell. Which matters, because far too many of us have become walking jail cells because of fear, or to quote the great Zora Neale Hurston, “People can be slave ships in shoes.” It is impossible to dance without at some point considering what it means to be free. When we surrender to the dance, at some point we will have to ask ourselves: “How much freedom can I stand?”

Some dancers are in constant physical pain or dance with bodies that have been repeatedly violated. Yet we dance–even amongst the wreckage. You don’t have to be fully coherent to dance, your dance doesn’t have to make sense. You are, however, required to be honest.

Dancing resuscitates the soul of the viewer. The dancer, alone, affirms to the lonely, “Share my body in this moment. Seek refuge in my dance. There is no need for shame. What happened to you, happened to me. And we shall overcome.”

When the Black body dances in America, her dance affirms us all. We know what has been done to her and–defiantly un-destroyed–she expresses herself anyway.

When I refer to the Black artist here, it is with excitement, because the blues is exciting; art created from devastation reminds us that the human spirit cannot be vanquished.

To be clear: this is not about magical negro-ness or taking on a society’s sins; this isn’t masochism for the sake of art. It is never the dancer’s responsibility to restore us to our courage; only to remind us, through her commitment to herself and her art, of our own shining potential. Which is not just an artistic but a human dilemma: we all have to negotiate, at one point or another, our relationship to society, to our tribe. What price do we pay when we tell the truth? How much freedom can you stand?

We live in times of extraordinary chaos and mystification. We may feel confused and deeply unsure of what step to take next. But not having the answer doesn’t mean we’re allowed to ignore the question. And there is a profound question presented to the Black artist: How did I get here? How many have died, been driven mad or to suicide, have had to fight against so much pain daily that they will never tell the tale? And if I don’t tell it, who else will?

The black dancer becomes a spiritual medium, a channeler of ghosts. This must be the spook house. So many lost, so many gone. It hurts sometimes to witness, but the untold story compels us. The blues never rests.

And it’s not all sadness, either. To people who are familiar with heartbreak, experiencing the erotic can, at times, be just as terrifying. We must bear witness to delight, to humor, to making love, to adventurous travel, to sunrises–if it’s true and we recognize it, we tell it all.

It is always tempting and can be a form of self-sabotage to criticize the choreography, to over-analyze the steps. We can debate genres: you insist on ballet while I prefer tap; we argue over contemporary versus classical dance and both dismiss freestyle. You do a tour jeté while I stand beside you doing the hucklebuck. Whichever way we choose to tell it, we must agree on one thing: the story must be told. And while we may not always get it right, it is very important right now that we try.

The blues tradition informs us that the chains that bind may not come off in this life. But, as I witnessed at the wedding, with the alchemy of the artist, we can transform the sound of those chains into music, a rhythm that acknowledges our bondage while it inspires the dancer’s longing to be free.

And she inhabits the space, the dancer and her blues, revealing while in motion the motivation of every artist who chooses to be brave: I may not have told it all, but what I have told is true. I couldn’t get it all out, but when it was over, I released more than I held inside. I need you to know the truth of these times; I need you to know who I am. Meet me in this place of discovery, where you recall your dance through mine, the dance you did before you knew fear or censure, as we transcend these chains together.

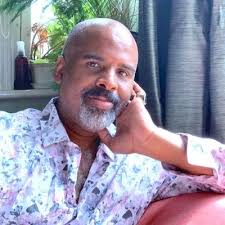

Max S. Gordon is a writer and activist. He has been published in the anthologies Inside Separate Worlds: Life Stories of Young Blacks, Jews and Latinos (University of Michigan Press, 1991), Go the Way Your Blood Beats: An Anthology of African-American Lesbian and Gay Fiction (Henry Holt, 1996). His work has also appeared on openDemocracy, Democratic Underground and Truthout, in Z Magazine, Gay Times, Sapience, and other progressive on-line and print magazines in the U.S. and internationally. His essays include,“A Different World: Why We Owe The Cosby Accusers An Apology”, “Faggot as Footnote: On James Baldwin, ‘I Am Not Your Negro’, “Can I Get A Witness’ and ‘Moonlight’”, “Family Feud: Jay-Z, Beyoncé and the Desecration of Black Art” and “How We’ll Get Over: Going To the Upper Room with Donald J. Trump.”

Photo of Max S. Gordon by Rufus Müller

*I really want to thank Angela Davis for giving me the strength and the power to write this response. Last Summer, during the height of the social justice uprisings, I started watching YouTube videos of Angela Davis’ speeches and lectures. Recently, I watched her lecture at UC Santa Cruz called “How Does Change Happen?” It’s almost an hour long, and it’s incredible. YouTube recommended it to me right when Lauren Warnecke published her article “Chicago dance has had a long love affair with process. Doubling down, are their audiences on board?” on See Chicago Dance. See Chicago Dance is “…a nonprofit service organization with the mission to advocate for the dance field and strengthen a diverse range of dance organizations and artists through services and programs that build and engage audiences. Our two-pronged approach focuses on building audiences while developing a more cohesive dance community.” They also have a dance criticism/review department. Warnecke is the editor for this department.

This is a response and the reaction to that article.

“This is not the way things are supposed to be. This might be the way things are now, but this is not the way things are supposed to be. They will not always be this way.” -Angela Davis

When I was awarded the Digital Dance Grant from Chicago Dancemakers Forum to create my podcast, The Process, my first thought was, maybe this will inspire dancers and dancemakers. Maybe talking about the process of creating will help us feel connected to the root of our work. While we grieve the state of our field, we can also stay connected to our identity. The public announcement happened on February 1st, and the next day Warnecke’s article was published.

After reading what Warnecke wrote, I felt disappointment and anger. Warnecke has a history of bad rhetoric towards artists of color and towards dance works that do not fit her personal dance values. Warnecke is from the ballet world. Her eye is towards the Eurocentric dance that favors white supremacist values. She assumed I was making my work for the audience rather than thinking, maybe, I was making something for artists. The conversation, right now, cannot be about what the audience needs if those needs uphold white supremacy. Her continued focus on a particular audience is narrow and leaves out a wide range of dancers and dance-makers.

It’s Black History Month, and the loudest voice in Chicago dance chooses to question the relevance of my voice. How and why was this published? I’m still unclear what Warneke’s intention was in this writing. However the impact is what I was left with, and the impact is what is still sitting with me. I am still working through my anger and disappointment at Warnekce wanting me to become digestible for the white gaze.

I made the decision to respond to the article. “I think I’m just not afraid of being the voice to say something anymore,” I texted my friend Erin Kilmurray. I could not be silent about Warnecke’s harmful writing while she collected a check and profited off my harm. Enough was enough.

I posted my public response on Facebook and Instagram knowing that it would start a conversation between the dance community and force Warnecke and See Chicago Dance to respond. Like so many supposed arbiters of the quality of dance, they are slowly realizing that they must hold some awareness of the artists they cover. They can no longer brush off the many folks commenting and tagging them. They can no longer ignore how they’re being dragged across social media.

Warnecke responded. We talked. Just the two of us, with a mediator, on Zoom. I left the conversation feeling lukewarm. The next day, See Chicago Dance’s executive director, Julia Mayer, released a statement. In it, the organization lays out the actions it says it will take–but without providing a timeline, and that allows them to avoid accountability. That behavior is not good enough anymore.

Did I want Warnecke fired? Honestly, no. I want her to understand the power of her platform and position. She has a unique responsibility that must be handled with care. Chicago dance doesn’t have many people writing about it. Warnecke is the biggest voice in Chicago because of her connection to See Chicago Dance, The Chicago Tribune and occasionally Dance Magazine. It’s unacceptable for her to have that many platforms and misrepresent Chicago dance.

“It’s important to work with your imagination and to use your imagination to think beyond the moment. It’s simply not enough to simply imagine a different future. Critical habits must involve collective intervention.” -Angela Davis

After my public statement, I had several conversations with peers and with some folks in leadership positions at Chicago dance institutions. My friends were not surprised that Warnecke wrote what she did. The individuals in leadership were…hesitant to speak their truths. There was an overall feeling that they did not want to fight this fight. One leader even said they were hoping nobody would pay attention to her writing and it would just go away. They were aware of Warnecke’s rhetoric, but they had no interest in trying to challenge her.

It became clear that the people in power don’t understand the magnitude of what is happening. They don’t understand because it is not their body, their work, or them being vulnerable on stage in front of one person with a history of racist journalism, a writer who has done nothing to do better.

That’s when I realized: they can only care so much and no more. They won’t join me in this fight. Predominantly white-run dance organizations cannot be fully invested. That would mean a shift in power, and they simply don’t have the imagination yet.

From the response that I got online, I connected with a few friends and peers and took the conversation, of course, to Zoom. The conversation began with our frustration about Warnecke and SCD, but then it changed when one person asked the simple question, “What do we want? Is this just a space that is just conversation, or is this a space to possibly do some work to hold accountability?” The decision was, unanimously, accountability. We moved forward with the idea to create a sort of community response on how writers, presenters, funders, curators, producers, and institutions of Chicago have been doing good and where they need to do better. If we had the space to say how we felt others deserve to have that same opportunity.

As a collective, we made Google Forms, drafted emails, created timelines, and brainstormed opening statements. We listened carefully, making space for all ideas. We reached out to over fifty Chicago dancers and dancemakers. Everyone’s thoughts will be collected and presented for all the powers that be to read, digest and–we hope–respond with action. We don’t aim to establish a monolith of thought, a set of rules. Our goal is to provide a clear path for the people in power to do better. Let your imagination run.

“Use knowledge as a transformative approach to change to remake the world in a transformative way that is better for all its inhabitants.” -Angela Davis

I simply cannot handle any more poorly written statements of solidarity. Why must small, independent artists–who have most to lose, especially now–also be asked to do this labor? Nothing will ever happen if someone doesn’t take a risk. Challenge your leadership and your board to take risks. Remove people from power who will not step up to those challenges or are resistant to losing their power.

Stop telling us what you see and show us what you can do. This is urgent but will not be solved in haste. It’s time for three-to-five-year strategic plans that identify and tackle organizational problems and offer solutions for accountability. I won’t sit in your Zoom calls anymore and hear you say how surprised you are that this is happening. You say you are here to serve us, but you’re only serving yourself, your own personal timeline, and protecting those in positions of power. Stop. That system isn’t working.

I’m writing this on March 8th, right in the middle of Chicago’s Fool’s Spring. It’s warm and everything feels so exciting, and change feels possible. The Collective is still gathering information, drafting opening statements and deciding on formatting. We have a meeting tonight to check in and talk about our next steps.

Personally, I’m hesitant to imagine what can come from all of this. The warmth of right now is tempting, but I’m scared to get my hopes up. When you’ve been failed so many times, your only line of defense is to keep your expectations low. I won’t be fooled into any more black squares. I just want for leadership and board members to read this and acknowledge where they’ve been unsupportive and decide where they can and should be reactive. Show us a real first step. We are ready and waiting.

*I hope that any artist in any medium who reads this can walk away feeling empowered to speak up when it is necessary. Those that are in power are not the be all and end all. They are here to amplify our work and our voices. They serve us.

*The Community Collective Response will be published in the Spring of 2021. This writing will be published in May of 2021. Hopefully, something good has happened.

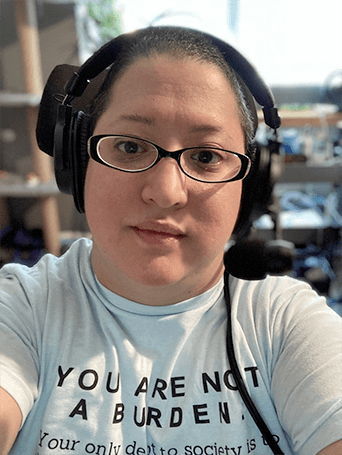

Alyssa (Uhh-lee’sa) Gregory, originally from Northern Virginia is a Chicago-based performer, choreographer, teaching artist, and arts administrator. She holds a BFA in Dance & Choreography from Virginia Commonwealth University and a Masters of Arts in Performing Arts Administration from Roosevelt University. During her time in Chicago, she has worked with companies and artists such as The Moving Architects, Joanna Furnans, Kristina Isabelle, The Leopold Group, Jenn Freeman, and Erin Kilmurray. Her work has been presented at the Chicago Fringe Festival, Salonathon, The Fly Honey Show and the Ruth Page Center for the Arts. Alyssa teaches dance all around the Chicagoland area and has worked as associate choreographer for The Fly Honey show for the past four years. She is currently the Marketing Manager for the Dance Presenting Series at Columbia College Chicago.

Photo of Alyssa Gregory by Anjali Pinto

Join us May 28 & 29 for the world premiere of J. Bouey’s Chiron in Leo. Informed by an astrological aspect in J. Bouey’s chart, Chiron in Leo brings about a healing of the inner child by addressing trauma and modeling healing practices that could benefit witnesses.

Listen to or read the transcript of a special sneak peek audio clip exploring choreographer and performer J. Bouey’s creative process. Click to listen or read.

To purchase tickets for this upcoming online film premiere and discussion, visit gibneydance.org/calendar.

I’m breaking up with dance.

My teacher at The Kirov Ballet wouldn’t be surprised. She told me, “It’s a pity you don’t have better training. You could’ve been something.” My last teacher at San Francisco Ballet might be sad. After saying, in one breath, that I was the top student in her class and, in the next, informing me that I was being dismissed for being Black, she told me to “never give up.” The administration’s 2020 Black Lives Matter Statement did nothing to mend my childhood broken heart.

I’m breaking up with dance–or breaking up with whiteness?

A company director took my height and Black body to mean I must have the strength of a cis man. I was bullied into a role my hypermobile body could not support, and I tore the tissues in my shoulder beyond repair. Now I have a permanent disability.

Many at the company called me “lazy” and “difficult.” Their worker’s comp insurance is still fighting my claim. But don’t worry, they too released a Black Lives Matter Statement this past year. I think they meant Black lives more as a concept, rather than a reality–or, at least, not my Black life, my shoulder, the ending of my career as I knew it.

I’m breaking up with dance because, ten years after I last set foot in an institution where I had to fight for placement in class, for representation, only to have them tarnish my reputation with other local companies, they still use my Black body on their marketing fliers. Black lives matter to them when they’re two-dimensional images that cannot speak.

I’m breaking up with dance because I once spent over eight hours in a day on pointe with nothing but a paper towel and a little tape around my major toe joints to try to feel the floor better and accentuate my meager arch. I bled through my pointe shoes that day. When I gingerly peeled my bloody tights away from the mangled skin of my toes, I felt pride, not horror. It took me years to realize my Black body, my Black life had to matter to me first, and I had to stop contorting it and abusing it to fit somewhere it was never meant to belong; the belief I’d been fed that I had to be a part of western white concert dance was the only way to be of value, was a lie.

I’m breaking up with dance because it’s not expansive enough to hold me. As an artist working at the intersection of social justice, queer making, and embodied storytelling. I am something that western white concert dance was never designed for, and it should be scared of me. The movements that I’m building run wider and deeper than the white supremacist and hetero-patriarchal values that white concert dance is born from and perpetuates, and I’m here to make sure it ends.

I’m breaking up with dance because I see white supremacy as inescapable as long as the structures that are built around the capital “D” dance world exist. Any dance form tied to the inequitable power dynamic between funder and funded demands an unsustainable urgency from artists. We have to constantly be in production because this system funds projects. It doesn’t sustain people.

Artists are reduced to our creative and economic output, and our human needs, our care, our lives are left out. This isn’t a system where people thrive. It’s one where bodies are broken because of their humanness. The part that perhaps doesn’t quite fit the mold, the part that needs a day off, the part that cries or bleeds has to be stamped out. The tragic part is that this is the part of us that dreams.

What would each of our values as individuals, collectives, and communities look like if funding supported lives rather than products? What portals to new worlds would we discover if we had time to dream?

I don’t have all the answers to these questions. But I do know my ancestors were force-fed trauma from their enslavers’ tables their whole lives, and that those lives were sacrificed at the altar of urgency and productivity. Yet somehow, inside their guts, they transformed that brutality into something new–like the way they wove maps to freedom into their hair when they weren’t allowed to read or write, when the rhythm of brutal, grinding work became a dance, or they took the cast-aside food scraps of their captors and made chitlins into a down-home delicacy.

That transformation is the way to liberation. I have digested dance, my own grief, rage, blood, and bruises. And, in the alchemy of my digestive tract, it’s been transformed. It has become both a vision for a liberated future and a returning to the freedom that was always mine. I’m breaking up with dance because I cannot heal in the same relationship that hurt me in the first place. And I want to heal. I want US to heal. I want to remove the harmful confines so often inflicted on Black dancers, whose bodies, cultures, and ways of knowing are ignored while we try to fit into the standards that our beautiful bodies were never designed for.

I’m breaking up with dance, and I am already in a pretty serious relationship with a new mode of being. One that honors the fact that my artistic practice is highly intuitive, and intuition is unconcerned with urgency. One where I don’t have to separate being a curator, a teacher, an activist, a community builder, and healer from being an artist. These are all my art; they are all valuable whether they crisscross, intersect, and interweave in ways that make sense to the capital “D” Dance world or not.

Here, inside this movement born of the digestive magic that transformed my own trauma into healing, and changed me from dancer into transdisciplinary artist, I am, you are, we are allowed our full personhood, to experiment with different ways of moving and being, because it’s not about a seat at the table–fuck the table!— let’s have a get down on it, to music of our own making, and use its materials to create something better; something that leaves no one behind, and is all our own.

Kai Hazelwood is a transdisciplinary artist, educator, event producer, and public speaker raising the profile of bi+/queer and BIPOC community issues through art projects, community events, and public speaking. She has appeared in BuzzFeed videos and speaks at community events, high schools, and colleges about bi+ and BIPOC community issues.

Kai was the founding Artistic Director of Downtown Dance & Movement, a state of the art dance and performance space in Downtown Los Angeles before it closed due to COVID-19. Kai was a 2018 Artist in Residence for the City of Los Angeles, and was invited to Jacob’s Pillow as part of the National Presenter’s Forum. In 2019 Kai was selected to participate in the Dance USA Institute for Leadership cohort.

Kai is co-founder of Practice Progress, a consultancy addressing structural, professional, and interpersonal white supremacy through body based learning that serves non and for profit businesses, educational institutions, and individuals. She is currently an adjunct professor in the dance department at Chapman University. Kai is also the founder and artistic director of Good Trouble Makers, a practice driven arts collaborative celebrating plural-sexual/bi+ identities and centering BIPOC. Good Trouble Makers are dedicated to making. Making art, making room, making change, making good trouble.

In 2020 Kai and GTM received an Artistic Impact Award from Invertigo Dance Theatre and funding from the city of West Hollywood. Kai and Good Trouble Makers are the first virtual Artists in Residence for Pieter Performance Space and then premiering an interactive virtual performance at The Musco Center in Orange County.

Photo of Kai Hazelwood by Adrien Finkel

During these strange quarantine days, I find myself in the most unexpected circumstances: confined completely to my Harlem apartment, mostly the tiny dance floor in my kitchen, unable to make any kind of physical contact with anyone, and yet, suddenly quite famous. I think it was the USA Today article that really changed things: suddenly, I was being approached by radio podcasts, magazines, news programs, all sorts of media outlets, and my email inbox was spilling over with messages from people who wanted to study with me.

And who am I?

I like to characterize myself as a crazy blind lady dancing by herself in her kitchen. While this description is accurate, I ought to think about the reasons why I choose to use these words, which reveal a desire not to take myself too seriously, but also might reveal the scars of trying to be taken seriously as an artist in an ableist world.

The last few months aside, I have spent most of my career as an artist fighting for any and all kinds of scraps: opportunities to perform, maybe in exploitative work, maybe in respectful work; opportunities to make professional connections, maybe with people who share my philosophies, maybe with people who think of me in ways that I find degrading; opportunities to make a little bit of money here and there, never enough, just anything; opportunities to teach, to use my hard-earned Masters of Education degree, my extensive study of biomechanics, and thirty-six years of classical ballet training. If I managed to grab hold of any of these things in any quantity, I knew that I needed to feel grateful, because chances like these for artists like me were few and far between, chances for blind artists. I learned to not ask for too much, I learned to swallow my pride, especially when all I really wanted was to beg for someone, anyone, to just talk to me.

At its most basic form, audio description is someone talking to you, using a voice and some words, to tell you what your eyes cannot. As performing arts venues have started to consider accessibility for disabled audiences, audio description has become a topic of some interest in the arts. The question sometimes arises: what is the best practice for audio description? Panels of intelligent people with extensive knowledge of performing arts theory discuss this question. Whether they come to any resolution, I could not say, considering that I have never been invited to be part of a panel like that.

What I do know, though, is what the audio description services are like when I attend a performance, whether live or digital. Usually, I find much to be desired, but I have been trained to smile and feel grateful that anyone offered me a headset at all.

Quite a few years ago, a friend had a ticket for a performance of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater at City Center and couldn’t make it. So, I got to go in her place. I got my little headset and sat myself down in what I knew to be a very expensive seat (grand tier), but I was really very far away from the stage itself and would not be able to feel air resistance from the dancers’ movements or hear their footfalls. This program included Alvin Ailey’s Revelations, a piece I had always wanted to experience. I sat there, listening to the little voice in my ear describing diagonal pathways of movement, whether right and left arms were straight or bent, how many dancers were on stage, the colors of their costumes, in the most neutral tone of voice that a human can produce. The people sitting around me, however, were, for the most part, in tears.

I heard people crying, laughing, crying and laughing at the same time, gasping in joy and surprise. Now, I’m not a detective, but I could tell that I was not experiencing the same performance that they were. I was getting my audio description, I was having my access need met, and I should have been grateful for that, but I didn’t feel grateful in that moment. I felt the deepest, most powerful FOMO* that any blind person could ever feel. (Note: FOMO is an acronym for Fear of Missing Out. It describes a certain kind of social anxiety that stems from the fear of being excluded from important events and activities. I believe that FOMO is in general popular use, but I know that it is heard frequently in disability community to describe the desire to participate in life, but being afraid or unsure that our access needs will be met, and that we will be left out.)

I wanted to experience a performance that would make me respond like everyone else in the audience. I considered to myself that these folks would be remembering this performance for years, maybe the rest of their lives, and that they would remember crying in the grand tier at City Center. I also considered that they would not remember everything about the performance. I suspected that whether the dancers’ right or left arm was bent or straight was not going to be the most permanent part of their memories.

Audio description is still a rather new field. Most of what is considered “best practice” for audio description is meant for television or film, media where the performers typically speak; actors act and emote with their voices. The neutral voice in that context sometimes makes sense: it is better to interpret the emotions of the performers based on their performances rather than through explicit description. However, in dance, performers only very rarely speak. The emotional content of their art is conveyed through movement. Is the neutral voice really the best choice in this circumstance?

Quarantine, in its strangeness and its totality for me, an immunocompromised disabled person, has encouraged me to start asking many questions about audio description. I have spent most of my quarantine trying to establish myself as a ballet teacher. My class, Dark Room Ballet, is designed specifically for the educational needs of blind and visually impaired dance students, particularly those who have never gotten to study dance before, but who want to learn the real skill. I speak continuously and constantly through class; a Dark Room Ballet class requires me to develop a rhythmic script which requires about six or seven hours of preparation before I teach. I have this style of teaching coursing through my blood at this point: I dig my heels in before every class and I think about how every movement feels and how to express it in the most musical but most complete way possible. What I have ended up doing, interestingly, is teaching a ballet class where I never talk about what anything looks like. My students learn quickly and learn a lot, they ask me exceptionally well-formulated questions about movement, and I know that some of them are considering professional dance careers. We accomplish this as a group without ever talking about what anything looks like.

Maybe that is the real flaw of audio description for dance, I started to wonder: the language chosen in most audio description is focused on what movement looks like, rather than what it feels like.

Some of my students have never had sight. They don’t have a list of visual shorthand in their memories that can tell them what a bent arm symbolizes as opposed to a straight arm. Honestly, at this point, neither do I. Perhaps only the most visceral type of audio description, the type that can activate the motor neurons in their own bodies, would be interesting to them.

What sorts of words could do that? What tone of voice? I think it is the tone of voice that those audience members who shared the grand tier with me at City Center would have had when they shared their experience with a friend the next day: intense, passionate, deeply connected to the emotional content of the artistry. Was it an accident that two of my closest friends are audio describers of this kind? For those of you lucky enough to remember life at Gibney in the Before Times, they might have noticed that I came to many performances there, usually with either Michelle Mantione or Alejandra Ospina, or both of them, sitting next to me, whispering to me while I can barely keep my body still in my seat.

Maybe describing the visual component of dance is less important than the visceral when developing audio description for dance. Maybe, when we develop performances, we have trained audio describers working alongside us during our rehearsal process. Maybe–and this might be my most radical suggestion yet–artists might consider their blind audience as they develop work from the outset. Maybe dancers should be allowed to talk, to self-describe, to emote what it feels like to jump three feet into the air while they’re doing it.

I, myself, have been creating art for blind audiences for quite some time, both in collaboration with visually impaired artists like iele paloumpis and Kayla Hamilton, but also on my own, just creating art that I think my blind and visually impaired colleagues and students will find interesting and exciting and memorable. I never say what I look like as I dance because, truthfully, I neither know nor even really care. I say what it feels like.

Almost as a lark, I started to work on a screen dance project with a choreographer in California named Heather Shaw. She was a rare choreographer who thought interesting audio description could actually make a dance performance better for the whole audience. I came up with an idea based on the children’s game of telephone, where dancers would film themselves while listening to an audio description track, and audio describers would describe said dance videos, and the chain could go on and on, perhaps evolving along the way, each artist taking their own spin on the expressions, different styles of movement, different styles of speaking, but all having lots of fun. The Telephone Dance and Audio Description Game, which might remain an eternal work in progress, a film that never stops collecting video and audio, is meant to welcome artists from both within and without the disability arts community into the experience of audio description, demystifying it, and legitimizing it as an art form in its own right.

Before I wrap up my thoughts, I want to clarify that I know that my ideas about audio description are unpopular, not only with arts institutions and dance companies, but also with members of the disability arts community. I don’t speak for every blind artist, and I don’t pretend to be able to do such a thing. I do, however, think it’s worthwhile for me to use my time to create dance performance and dance education for my fellow blind and visually impaired folks, and for me to try every possible way to change the script for audio description, to help it develop into a truly extraordinary art form, to actualize its true potential to help everyone in the audience laugh and cry at the same time together. What better way for a crazy blind lady dancing by herself in her kitchen to spend her time?

Krishna is the director and teacher of Dark Room Ballet, a pre-professional dance curriculum designed for the educational needs of blind and visually impaired people, the only course of its kind in the English-speaking world. Dark Room Ballet has been featured in USA Today (Green Bay Gazette, North Jersey News), BLOOM magazine, Speak Out for the Blind podcast, Eyes on Success podcast, and on Bloomberg Quicktake news.

Krishna Christine Washburn has performed with many leading dance companies including Jill Sigman’s thinkdance, Infinity Dance Theater, Heidi Latsky Dance, Marked Dance Project, and LEIMAY.

Krishna has collaborated with many independent choreographers, including Patrice Miller, iele paloumpis, Perel, Vangeline, Micaela Mamede, Apollonia Holzer, and most notably with A. I. Merino, who especially created her signature role, Countess Erzsébet Bathory, and with whom she founded the artistic collective Historical Performances.

Krishna boasts several ongoing artistic collaborations, including work with wearables artist Ntilit (Natalia Roumelioti). Krishna is the Artistic Director of The Dark Room, a multi-disciplinary project with fellow visually impaired dancer, Kayla Hamilton. Krishna is also the Artistic Director of The Telephone Dance and Audio Description Game, an on-going activist screen dance documentary project with choreographer and filmmaker, Heather Dayah Shaw.

Photo of Krishna Washburn by Micaela Mamede

Alejandra Ospina is a first-generation native New Yorker and full-time wheelchair user whose family has roots in Colombia. She has been active for several years in various advocacy and performance projects locally and beyond, and also works as an audio describer and narrator, in addition to being the Program Coordinator for Dark Room Ballet with Krishna Washburn.

Photo of Alejandra Ospina

“The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.” –Sigmund Freud

I’m not so sure, Sigmund, that dreams have anything to do with a quote royal road unquote as you once wrote.

They’ve always seemed to me, actually, to be the slushy, unplowed street in some obscure neighborhood with poor political representation. Or–let’s go with this a little, Siggy–a sanitation system that sometimes works better than at other times. Dreams, for me, seem to be the way the brain takes out its rotting garbage.

Can you tell that, for the most part, I’ve never liked them, trusted them?

I survived them when they were the terror of my childhood until I mastered what needed to be mastered and became a dream ninja no longer fleeing but turning and confronting what I was fleeing from room to room in the house in my obscure working-class/lower-middle-class neighborhood.

Sig, I want to share with you the dream I had overnight.

Typically, I don’t remember the context, the twisty, absurd way I got where I got. But this dream wound up with me and my wife in this car. And, suddenly, we were frantically pushing the retro buttons on our car doors. Why? Because there was a white racist outside carrying an assault rifle. He had some other people with him. I remember one woman, a white woman. I don’t remember the rest, and I don’t know why I remember her.

Oh, wait. Now I see it.

She was pointing out–with some amusement, mind you–that our car had some odd little window near the back on the passenger side. My side. Far back where it would have been hard for me to quickly reach around and lock it.

It was unlocked. It opened. Someone from the crowd opened it. Maybe she opened it.

In any case, small but big enough for a rifle to poke through. At any moment, he could have opened fire on us.

But he played with us, Sigz. The way a cat plays with a mouse. He didn’t even need that little window to slaughter us, now that I think about it. The regular windows would have just shattered, and he’d have us.

As it turns out, he wasn’t going to use the rifle. Not that time. But he wanted us to know he could.

Because it was all about getting off on our fear.

I woke up. I just took myself right up out of that.

I told my wife this dream when I woke her. I usually don’t bother her with this sort of thing. Like, why? But this time, I did.

And, of course, she said, “I can’t imagine why you’d have a dream like that.”

And we both shared a dark, bitter chuckle.

Because the angry men with the too-easy-to-get-your-hands-on guns are back making mourners out of us all from sea to shining sea.

It’s Atlanta’s turn. It’s Boulder’s turn. Whose turn is it next?

Will it be my turn? My wife’s turn? Your turn?

Really, no way to know. Because–thoughts and prayers and calls for laws that go nowhere–it’s still just too damn easy.

We need to check America’s background for rage towards women; check America’s background for racist and xenophobic violence; check and double-background-check for world views that view the world as a mortal threat to manhood and religion.

We need to get real.

When a middle-aged Asian American woman just trying to work and survive gets shot to death in a massage parlor, it is too close to home.

When a white man preys on Indigenous women without consequences, it is too close to home.

When a trans woman disappears and is never found, it is too close to home.

It is never far from home.

Our home, Sigmund, is where we live with one another. And that is everywhere.

Eva Yaa Asantewaa (pronouns: she/her) is Gibney’s Senior Director of Curation as well as Editorial Director for Imagining: A Gibney Journal. She won the 2017 Bessie Award for Outstanding Service to the Field of Dance as a veteran writer, curator and community educator. Since 1976, she has contributed writing on dance to Dance Magazine, The Village Voice, SoHo Weekly News, Gay City News, The Dance Enthusiast, Time Out New York and other publications and interviewed dance artists and advocates as host of two podcasts, Body and Soul and Serious Moonlight. She blogs on the arts, with dance as a specialty, for InfiniteBody.

Ms. Yaa Asantewaa joined the curatorial team for Danspace Project’s Platform 2016: Lost and Found and created the skeleton architecture, or the future of our worlds, an evening of group improvisation featuring 21 Black women and gender-nonconforming performers. Her cast was awarded a 2017 Bessie for Outstanding Performer. In 2018, Queer|Art named one of its awards in her honor, and Detroit-based choreographer Jennifer Harge won the first Eva Yaa Asantewaa Grant for Queer Women(+) Dance Artists. In 2019, Yaa Asantewaa was a recipient of a BAX Arts & Artists in Progress Award. She is a member of the Dance/NYC Symposium Committee and the founder of Black Curators in Dance and Performance.

A native New Yorker of Black Caribbean heritage, Eva makes her home in the East Village with her wife, Deborah. Sadly, their best-cat-ever Crystal traveled over the Rainbow Bridge on February 18, 2021.

Monica Nyenkan is a Black queer community organizer and arts administrator hailing from Charlotte, NC. She graduated from Marymount Manhattan College, with a Bachelors in Interdisciplinary Studies. Currently based in Brooklyn, NY, her artistic and administrative work focuses on creating equitable solutions with and for historically marginalized communities in order to make art more accessible. In her free time, Monica loves to watch horror films and share meals with her friends and family. A fan of educator and historian Robin Kelley, Monica firmly believes the decolonization of our imaginations will help facilitate a more radical and inclusive way of living.

Photo of Monica Nyenkan by Jakob Tillman

DISCLAIMER: Opinions expressed in Imagining: A Gibney Journal are the writers’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views, strategies or opinions of Gibney.