Imagining

A Gibney Journal

Issue 7

Letter from the editor

Where are your feet planted now, right now?

Are you good right where you are?

Or do you need to go?

How does your blood feel as it flows through your veins?

What does your blood whisper to your cells?

What is one thing you’re sure of—I’ve got this—at this very moment?

What is one thing you’re mourning for or longing for?

How are you Nature?

How are you Multiverse?

If you were to plant your garden on unknown soil, what would you hope to raise?

If you gave yourself due credit, what might you almost forget to praise?

What word did Spirit say to you just now?

What have you brought to the crossroads? And what are you leaving?

What must go…now!?

How do you get yourself free?

What were you meant to sing

What truth moves with you?

Eva Yaa Asantewaa

Senior Director of Curation

Editorial Director, Imagining: A Gibney Journal

A one year old is left by his parents in the care of their maid. The maid, and her friends, while playing with the boy end up somehow injuring him. At the time, neither parent can figure out why the boy is crying so profusely. Many months later, while bathing his child, the father notices something sticking out at the boy’s right elbow. He takes him to the doctor, who upon getting an X-ray of the injury, tells the father that his child has suffered from a dislocation in his right elbow. If detected immediately, the elbow can just be slotted back in, but at this point it is too late to make any adjustments without surgical maneuvering. The adults decide that it is best for the child to stay with the elbow as is, since it does not seem to be affecting his day-to-day activities.

I don’t remember ever having a right elbow that looks “normal.” For the longest time during my schooling life, my favorite party trick consisted of showing people my left elbow and then alarming them with my right. “This is what a normal elbow looks like, yes?,” I would say, gesturing to my left elbow. “Now, watch this!” Extending my right elbow violently, I would have people reach out and touch the bone sticking out. Responses would vary from intrigue to aversion to outright disgust. I don’t recall feeling any pain as a child; the elbow was not an issue, but simply a quirk. This early phase is what I call “ignoring.”

In college, when dance became my primary discipline, I began to get curious about my elbow. What had earlier been a subject of amusement began to become a subject of direct importance that had consequences on my day-to-day activities. For my anatomy class final thesis, I wrote a paper on “radial head subluxation,” the scientific term for my disability. In my choreography, I began to investigate the links between my elbow’s dislocation and my relocation as an immigrant in the United States. When someone noticed my idiosyncratic elbow in passing and remarked on it being very hyperextended, I would be sure to tell them that it was actually dislocated. I even interviewed my parents about the accident. My research led me to discover the fact that “Nursemaid’s elbow” is a recognised term used to describe the very accident that happened to me as a child. This phase of my life, when I finally began to investigate my disability from a scientific and historical standpoint, is what I call “questioning.”

When I graduated from college, I was desperately in search of community. More than anything, I wanted to dance in a recognized company, obsessed with the idea of “making it in New York City.” However, amidst all the ambition, I made the wise choice of taking yoga classes at a wonderful studio called Katonah Yoga in Chelsea. The founder of the studio, Nevine Michaan, offered me personal guidance and helped me recognize indirect ways of working with my elbow.

“I am not going to do anything to your elbow, but I am going to work with everything around it,” she would say, making adjustments to my back and torso in Downward Dog or Half Lotus.

Finally beginning to recognize that I was different, I enrolled myself to work with Heidi Latsky Dance (HLD), a world-renowned physically-integrated dance company. Between Katonah and HLD, I had some of my most challenging revelations, and made some of my fondest memories while in New York City. I call this phase “accepting.”

For a while after working with HLD, I stopped thinking about my disability on a regular basis. My relationship to dance, at this time, was at its most inconsistent. All I wanted was to stay busy and get recognition for my work. I overworked to compensate for my inadequacies. I constantly burned myself out, and my poor eating habits led to a diagnosis of anorexia with therapy visits and antidepressants.

What really helped me recover, though, was the time I spent with my parents during extended visits to Bangalore. Time away from dance, when I re-learned French, connected deeply with Iyengar Yoga, and travelled, re-ignited my passion for the discipline. This phase helped me recognise how valuable dancing has been in dealing with my issues, and is what I call “experiencing.”

Photo by Joshua Sailo • Image Description: Ainesh Madan’s dance photo where the author is seen leaping across stage in a jeté with arms extended.

In February 2019, I chose to return to Bangalore for good. It was quite a spontaneous process, although I had considered it for some time. My father’s ill-health, coupled with my own recoveries, led me to the decision to not renew my visa. What was supposed to be a three-month stay turned into a long-term shift.

Less than a year later, I fell upon the work of Frederic Matthias Alexander, which I had briefly studied during my first year in college. In March 2020, I officially enrolled in a course for people who wish to train to teach the Alexander Technique. I have not looked back since.

The work clarified to me the oneness that is fundamental to all sentient beings and how this oneness can be continuously strengthened. Finally, I had an answer! I could not only manage my disability but be empowered by it.

“Think of your arm as something not separate from you,” advised my teachers Béatrice and Robin Simmons numerous times. In all activities, then, I focused on engaging my back, and I started learning to use my left arm for day-to-day activities. It dawned on me that the only sustainable way to deal with my ailments and issues was to work on myself all the time. I finally began to recognise dance as my calling because I began to acknowledge that I had to rely on my legs more so than the average able-bodied male. If my disability was the curse with which I had met when I was one, dance was the super-power I had been gifted with to compensate for the same. This phase, which I consider to be ongoing, is what I call ‘“living.”

My journey with my disability is unique and personal, but perhaps others with similar injuries might relate to my process. Without dance, I might never have found the strength to speak about—let alone be empowered by—what I suffered. Dance has allowed me to find a sense of connection within myself, which I now recognize as fundamental to establishing a connection with others. I am still drawn to virtuosity, spectacle and technical prowess. Dance, however, is essentially the plaster that helps me fill the cracks that I cultivated in previous lives so as to continuously prepare myself for the next one.

Photo courtesy of artist • Image Description: Ainesh Madan’s self portrait, where the author is seen smiling against a background of posters on his wall.

Ainesh Madan (he/him) is a dance artist currently based in Bangalore, India. He is a founding co member of the 206 Dance Collective. Ainesh attended Bard College (USA) on a full-tuition scholarship, receiving a Bachelor of Arts in Dance and Economics. He has since choreographed numerous works, while also collaborating with, and/or performing for, various notable choreographers. Experimentation is foundational to Ainesh’s work. All his choreographic endeavours are distinct in form and content, and serve as reections of his learnings at the time they were each created. Ainesh’s choreographic choices are informed by his daily attempts to enhance his capacities as a dancer; for him, choreography is a tool that highlights the potency of dance as a medium for honest, unfettered communication. He is deeply interested in understanding, and practising, how dance can help individuals (performers and viewers alike) connect to their sense of wholeness. Ainesh premiered his first evening-length solo, Phantasies, as part of the University Settlement Guest Artist Series programme in New York City, for which he received the Emergency Grant from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts. He was also selected as one of the residents for Goethe-Institut / Max Mueller Bhavan Bangalore’s bangaloreREsidency-Expanded in 2020. Ainesh is currently working towards becoming a certied teacher in the Alexander Technique. He is also an experienced, multi-lingual dance teacher, and has been offering Pay-What-You-Can online dance classes since the beginning phases of the current pandemic. Given the opportunity, Ainesh would willingly spend all his time reading, journaling, meditating, playing an instrument, and most importantly, hanging out with his companion.

Support: PayPal @aineshmadan | Google Pay: ainesh.madan-1@okaxis

Website: www.aineshmadan.com

This dialogue is transcribed from a longer Zoom conversation between dance artist Benjamin Akio Kimitch and dramaturg Jeffrey Gan on August 21, 2021. The two have been in ongoing, virtual-only dialogue since November 2020. This is Kimitch and Gan’s first time working together and Kimitch’s first time working with a dramaturg. Kimitch’s background in Chinese opera movement has been a starting point for this new work, in part because of its core influence in the development of Chinese classical dance in the 20th century, to reimagine contemporary choreography and de-center western hierarchies. Together, Kimitch and Gan speak on mixed-race identity and the tension between the impulse for authentic representation and the positioning of traditional forms. The project will premiere at The Shed in 2022.

Jeffrey Gan

You know, one can imagine a different version of this project, where it just springs from your head, you put it on some people and it doesn’t really matter who they are, as long as they have the facility to do it. But it’s about the conversations that you can have with these people. Which is very different from being like, “Here is the movement, you don’t need to know about the context, you don’t need to know about where it’s coming from.”

Benjamin Akio Kimitch

Right. Right. Which is how a lot of people work. I like that you brought that up, because one of those big core questions has been, “Who?” Who are the dancers, and who are the people in the piece? It’s become people who have been invited in with a lot of thought and intention around it. And now taking stock of those choices, I’m realizing, as you pointed out, that the dancers don’t all share the same kind of facility, the same style, the same dance history. All of my dancers entering into this project are not trained in Chinese dance, which we talked about, and that was intentional.

JG

Could you talk about that intention a little bit?

BK

Well, actually I don’t know what the intention was, to be honest. So many of the decisions are simply based on what is available to me. I don’t actually know a lot of Chinese dancers or Chinese opera performers who are in New York and with whom I can engage questions that are centered around curiosity, experimentation, breaking molds, questioning conservatism. These things are really tricky, especially when you’re dealing with a cultural tradition. So I’ve invited in these people: Pareena Lim, Lai Yi Ohlsen, and Julie McMillan. Julie, I’ve worked with for a long time, for like 12 years. So there are these shared experiences, a shorthand that is definitely a reason for her to be involved. Pareena and Lai Yi I’ve never worked with before. But we’ve engaged together outside of the context of a choreographer-performer dynamic. And there’s just some kind of vibe, like we share a philosophical entry point into how we want to make work or how we want to be involved in dance and contemporary dance. And then Pareena, Lai Yi, you and I each have our own distinct relationship to our Asian heritage, which are all very different.

JG

To me, I think that’s part of what I find so compelling or so interesting about this. I feel like if you had come to me, and you’re like, “Jeff, I have this thing. I have this troupe of ten Chinese performers, we’re all out of the system, like straight from Shanghai or something, and I want you to be the dramaturg for this.” I’d be like, I think we need to find someone else. Because I would not feel grounded. But I feel like there’s something about this piece to me that speaks to being a kind of forum for talking about what it means to be Asian in America. And also for the two of us to be of mixed race. For me, my experience and that kind of identity is so much about how I don’t really know what kind of ground I’m standing on. I’m always feeling uncertain if I have a foundation or if I’m speaking or grounded in a kind of authentic place. Do I have the authority to speak on Asia, you know? Or America? I think that’s a big thing that I struggle with and I think that can be a place of insecurity for me. But it can also be a place of great strength. I have a friend, kt shorb, who is—one of their parents is Japanese and the other is a white person. And they talk about how they really don’t like fractional language. When it comes to identity and ethnicity and race, they really prefer whole numbers. They would say I am wholly Asian American, I am wholly white and I am accountable for both of those things. And that’s a really tricky thing. My voice is not diminished because of that, but it also means you’re accountable for a lot of other stuff, too. So I feel like the fact that you’re working with the people that you are and that you’re raising the kinds of questions that you’re raising, it just seems to me like it resonates so much with that discernment of like, What is going on? How do we speak to this? What do we speak about? It feels to me like so much at the core of how I move through the world outside of the arts, or maybe especially within the arts too.

BK

Wow, yeah. That’s all really great. I sometimes forget that those are really good things to remember that this project was and is about trying to find some kind of ground. Like, what is authentic? What of my memory is authentic? What did I learn as a Japanese American within a Chinese form? What of that is real? And I love your friend’s term: the fractional identity.

JG

This is so embarrassing to admit. I remember being a kid; I would make these pie charts in my notebooks with different little slices being like, what slice of me is Chinese and like—why is it useful for me to be like, “Oh, well, my grandfather was from an indigenized Chinese community in maritime Southeast Asia, and so thus I can say that I am like one-fourth Chinese.” That isn’t helpful. I don’t get to speak a fourth of a sentence about this kind of stuff, I don’t get to have a fourth of a point of view about a hate crime or something. I have a full point of view about that. And I can’t point to a part of my body and say this is the Asian part of my body. So yeah, I think that that’s kind of why I find your project so compelling. This is also a piece about movement. It’s a dance. It’s a piece of choreography, as opposed to a film or a poem or something. Because how do we know when we’re speaking authentically or if our experiences are authentic? I think we feel it comes from a corporeal experience, doesn’t it? Like you, your body was in China, your body was learning how to do these body-things in that context. And then people’s bodies are going to be on stage, physically in front of people. And I think that is really important.

There’s this restaurant that I really like in Oakland, called Lion Dance Cafe, and it is a vegan, Singaporean restaurant, and it is some of the best Southeast Asian Island, Southeast Asian American food that I’ve had here. And all over their website, all over their condiments, their motto is “authentic, not traditional.” The idea that you can have a taste of this condiment that, you know, because it’s vegan, but usually made with like shrimp and other animal bits, but it can be authentic to you. Your dance can be authentic to your experiences, the flavors that you’re gunning for, but it isn’t necessarily like it’s going to be a traditional piece, you know. You are so concerned about tradition and giving proper due to this long tradition, this lineage. So what does it mean when it comes up against trying to be authentic as well?

BK

Right. When is tradition and authenticity no longer two of the same thing? I haven’t figured that out yet. For the last year before beginning a process inside of a dance studio, I’ve been reading a lot to open up the histories that I have determined to be my personal dance history. As I’m opening up these histories, I’m realizing that the traditions I seek are more a modern-day perception of tradition. And I’m still trying to unpack that. And then there are traditions that can be something that is in your lifetime. I can have a tradition with my sister. How far does a timeline go back in order for it to be tradition? I think I’ve been using the word tradition to replace something else that’s about reverence or some kind of historical recreation. But there’s something much more interesting and nuanced that’s coming up.

JG

I think that word tradition sets something out of time, and a tradition is a thing that doesn’t change. And I think that’s a place of immense power to be like, this was given to me who received it from so-and-so. This lineage. If something is traditional, it has all this sort of capital. And when you’re talking about forms that don’t come out of the Euro, North American world, tradition is a way of eliding a kind of specificity almost. If someone was like, “I don’t like that,” they would feel disempowered because they’re sitting on this tradition that is so old, ancient and timeless. But if we just say, this is our authentic response to these things or to these questions that have come up in ourselves, I think that locates it in our bodies. It makes it much more specific in a different way. To say this is authentic because it’s authentic to you, to me, to us; as opposed to this is traditional, so it’s traditional to the world, or to a country of a billion people or something, and you represent those people, on behalf of tradition, you know? I think that’s a profoundly different project, maybe.

I haven’t played Gamelan for like over a year now (and it kind of breaks my heart a little bit). When I bring my friends who were not part of the ensemble into the Gamelan room, I’d be like, Oh, it’s traditional. We have to take off our shoes. And we can’t step over any of the instruments, we have to step around them. And when I lived in Indonesia, people in the Gamelan ensemble there would be like smoking and eating things. They would take the food wrappers and put it into the tubes. And I was like, wow, what is tradition? Then like, what are we doing in Texas? What kind of lineage are we receiving? But does that mean it’s fake? It’s just authentically something else. You know, like we can’t repair these instruments very easily. If a thing is broken, it may be broken forever, or it’ll be a decade before we have someone in who can repair this instrument. So our relationship to them is charged in this way. Like weirdly subsumed under a kind of quasi-Javanese spirituality about the spirit of the instruments and the spirit of a Gamelan. But when I would go to Java, be in a village, and there’d be a Gamelan, I’d be like, “Oh, are you having like a blessing for this Gamelan at some point that I could attend?” And they’d be like, “I mean, we don’t really do that anymore. Like, we’re all Muslim. We don’t really believe in, like, the spirit of these instruments or whatever. Sorry.” And I’d be like, “Ah where is the tradition,” you know? Yeah, I’m making it sound like I’m a clown. Like, I’m sort of the clown and like the butt of all of these things. But I think it’s just different. We have an authentically different relationship that are sort of traditional labels, and it was eliding all kinds of stuff inside of that.

BK

I love that story. And it sparks for me when I was talking to my Chinese dance teacher recently at New York Chinese Cultural Center. He was talking about his observations teaching and learning in China versus in the U.S. How people in China, they’re not so worried about the past. China has such a long history, “We’re thinking about what’s in the future. What’s next.” So with Chinese classical dance, it is constantly moving forward. It’s not trying to be some kind of like, what do you call these…

JG

Like museum pieces.

BK

Whereas, here in the U.S., people are invested in the past and where they come from. I think there’s some kind of maintenance of the knowledge that fewer people have. In a Chinese dance recital in the U.S., it’s a lot about spreading an appreciation of a culture through the presentation of these dances.

JG

I think that’s what I’m hearing, what I was saying and what you’re speaking to now is a kind of scarcity. I think about these Tweets that I’ve seen, and they’re making fun of diaspora poets. And their poems are like, Oh, the monsoon rains / smell of the mangoes / Mama, why have you shut my mouth for our words, or whatever. The mangoes, mangoes. Where are the mangoes? And then it’s like, in the country of origin, the poets are like, Fuck you all. I wrote a heavy metal song. Here it is.

I think there’s something that feels so paradigmatically different about being like, What’s next? What’s next inside of a form that I see is always for pointing back to its past. From my perspective, being here in the U.S., I think there’s just something that we experience as Asian Americans is our culture feels sometimes scarce to us. In an American context, it is a minority culture. We’re often always making the case about who we are to a predominantly white audience, to predominantly white venues, to funders, to a public generally. And so, you end up grounding yourself in a kind of, you know, “tradition” in being like, I know it’s new to you all, but like I’m sitting in something that is much bigger than myself, and something that is very complex. You have to keep making the case for it, and I think it puts you in a backwards-facing place. That’s why it’s so wild to me, that someone told you, “No, in China, we’re always thinking about the new thing? What’s the next thing? We’re moving here.”

I think that you’re operating here at that juncture of these things, right? Because your audience is probably going to be the kind of contemporary dance audience that you were so accustomed to working with. And I think it’s a really important question of, if we’re going to grab ourselves and our authenticity and speak at a kind of juncture place, how much explaining is going to happen? How much contextualizing is going to happen? How much do we care about the audience being a part? I think these are really important questions. Maybe the answer is like, We don’t care. Maybe none of this happens. Maybe it happens, but it’s weird. And it’s like, kind of part of the game. It’s part of the schtick. But I feel like those are all sort of tied up in this question of having these multiple identities, of sitting on these junctures. That you’re not a Chinese person but you are someone who studied before. That you’re white and you’re Asian, that your dancers don’t have the sort of training that you have. That this is messy, it’s like messy, messy, messy. And I think in a way that I find really exciting. I am really stoked to see how you sort of pull it in.

BK

No, please say that to me more and more, because it’s my biggest crutch or complex around this. I love mess, but I’m afraid of the mess. And I’m more afraid of the Chinese person in the audience, to be honest. You know, like, the progressive thing to do with The Shed is to demand they do the outreach so that my audience is 80% from Asian communities, but somehow that’s not at the crux of what I’m doing and who it’s for. It’s just for me, actually. It’s for me and maybe like three other people I have in mind. I did write this in a grant, and I have no idea how it landed because I didn’t get it. But anyway they always ask you, Who’s your audience? I took a page from one of our conversations, and I tried to make a case that my audience are the people that I’m building this community of accountability with. These people that I’ve recently been having very intimate one-on-one conversations, as research for this project, about their experience being Asian and making contemporary performance work in America (Yasuko Yokoshi, Phil Chan, Jennifer Wen Ma, Charlie Mai, DaEun Jung, author Josephine Lee, and the folks who eventually became dancers and collaborators in the project). And I’m just like, Alright, I’m thinking of these ten people. And when they come to the piece, I hope they see our conversations played out in some way.

JG

I think that that’s really beautiful. It’s sort of a for-us by-us kind of feeling. It’s for the people that are making it, I think that’s a perfectly valid thing.

BK

We’re talking about the diversity, history and heritage of my dancers and collaborators, the people I’m inviting in. And there’s Julie who is white and without Asian heritage. And I’ve talked to her about it. I was very upfront with her. She was even like, “Should I be in this? I can be part of your process, but I don’t know if I should be on stage or something.” But I was like, “No, in my gut I feel like you’re in this piece. And you and I have made so many pieces together.” She is sort of this artistic muse, I guess, if I want to use that word. And these were very personal pieces about me grieving the death of my mother. The core threads of friendship and emotion and understanding felt more important than any kind of demographic virtue signaling in my piece. I still don’t quite know the deeper questions and answers about what is her place in this piece in terms of an Asian American experience. But here she is, and I guess I’ll find out in the next year.

JG

Well, I have a couple of thoughts about that. So one is a question that we can keep returning to, like how do you address Julie’s whiteness in this piece? And I think that’s sort of a cipher for another question, which is how do you address your whiteness or my whiteness as well? Because I don’t think we get to retreat. That’s part of being whole, you know, being entirely the thing. That I’m not being fractional. You’re accountable for both of those entirely. I also think it’s also really beautiful that you have a long creative relationship with this person. And that brings so much depth and beauty and authenticity to whatever ends up happening in this process between the two of you and between all of y’all. And outside of the kind of fun like, ooh, like, what is it? Like what are the implications and voice? I think it’s just true to your personal life to your lives together. And the experiences that you’ve had.

BK

Yes. And to just cast all of my Asian friends and think the work is done—that’s not a way to make a piece to me. And I just feel like I want to bring ideas and people in the room that I think are interesting. I’m sort of prepared for critics to come for certain parts of the messiness, and I’m also just trying to make a good dance. I’d rather the dance be good beyond just checking the boxes.

JG

But I would be questioning who are these critics that you are imagining? And are they people that you want to be accountable to? And I wonder if you don’t really care about, say, this character of the New York Times dance critic. Maybe if like Auntie from Chinatown has some things to say, that is part of who I feel accountable to. Or if Jeff comes in, and I’ll be like, maybe that’s not a great idea. And maybe I would ask you to take that seriously, and you’re accountable to me. I think that it’s very helpful to be specific about who we are imagining having these sorts of reactions. And if we feel authentically connected to them or not.

Photo of Benjamin Akio Kimitch by Da Ping Luo • Image Description: Benjamin is framed from the shoulders up, wearing a white T-shirt next to a brick wall. Light is directed on the left side of his face. He’s a light-skinned person with short, wavy, dark hair, brown eyes, looking into the camera with a relaxed smile.

Benjamin Akio Kimitch is a dance artist and producer living in Brooklyn, NY. His artistic work is deeply influenced by his mixed-race Japanese American heritage and childhood training in Chinese dance. Currently, Benjamin is a 2019-2021 Movement Research artist-in-residence as well as the program director and associate curator of Danspace Project. Benjamin’s next commissioned dance work will premiere at The Shed in 2022, following a 2021 artist residency at The Maggie Allesee National Center for Choreography/MANCC. His writing was recently published in the Movement Research Performance Journal, Issue 55. Benjamin’s 2017 Bessie-Award nominated work Ko-bu premiered at Danspace Project and was later reimagined for the Noguchi Museum. In 2015, he was a Dance and Process artist at The Kitchen. Kimitch holds a BFA in Dance from NYU Tisch and studied basic training at Shanghai Theater Academy School of Chinese Opera. From 2015-2020, Benjamin was the senior producer at Performance Space New York/PS122. He previously worked on the full-time artistic programming staff at the Park Avenue Armory, New York Live Arts, and Dance Theater Workshop.

Website: benjaminakio.com

Jeffrey Gan is a multi-media artist, dramaturg and PhD candidate in the Performance as Public Practice program at the University of Texas at Austin. His scholarly research and artistic practice explores time, food, and the performance of nostalgia in Indo and Indonesian diasporas. His interests include sensory ethnographic methods, tempo doeloe imaginaries, the labor economy of “ethnic” food and the racialization of Indo performers. He is currently a visiting fellow at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Southeast Asian and Caribbean studies. Gan’s installation and performance work has been exhibited as part of The Cohen New Works Festival and Center Space Project/TEDxUTAustin, and he has collaborated on projects with Salvage Vanguard Theater, Charles O. Anderson/dance theatre X, Sam Mayer, and Benjamin Akio Kimitch, among others. He is proud to play in Kyahi Rosowibowo, a Javanese gamelan ensemble in the Butler School of Music.

Photo of Martha Wittman and Nia Love by Jenny Gerena • Image Description: This is a moment inside a duet which takes place just after witches from all over the world and all over history have arrived for an important gathering. Martha Wittman and Nia Love are both calling out, but also supporting each other in the difficult work ahead.

Once I met a physicist who said to me: “The world exists so that I can do my math.” I thought about that for a split second and then said: “You mean the world exists so that I can do my dances?” He grinned and said, “why not?” Actually, I think the dances exist so that I can be in the world. (Hiking the Horizontal, p. 66)

First, it was just me, outside a museum in Edinburgh. I was on the lawn, furious, in pain, exhausted after having wandered through a gallery filled with images spanning 500 years of drawings of witches. When I had entered the exhibition, I wasn’t that interested in witches, although I had been drawn to feminist biographies, older women’s knowledges, and a deep and abiding belief in the underrepresented ideas of creativity, magic, mystical thinking and awe in almost every cultural setting I occupied over the years. But by the time I exited the show, I was convinced I had found my next piece. After all, what I had witnessed was female body parts as weapons, a grotesque representation of beauty, extreme symbols of hatred scattered on every inch of the canvases. How, I mused, could these be your sisters, mothers, aunts, grandmothers, daughters?

The following are a few stories of the journey while making Wicked Bodies. Lucky for me, the subject matter shapeshifted constantly, meeting not just my artistic desires but my and our personal needs to comprehend a deeply changing world.

ONE: Maybe it’s two brilliant crones, sitting on a bench in some backstage theater; half dressed, talking about their lives in dance and occasionally getting up and demonstrating. So, I brought Martha Wittman and Valda Setterfield together to do just that. In my mind, they wander onto the stage where a dance theater piece is underway. It’s about witches, and the two are embodying the sly joy, the subversive sexuality, and absolute power they employ while discussing the matters of the day. It’s irrelevant whether they are good or evil. In the end, they each bend their beautiful old bodies, tied cross armed from wrist to ankle and then they are submerged in water, murdered as so many women were so long ago.

Photo of Leah Cox by Greg Nesbitt • Image Description: Leah is making a spell, one of the great inheritances we assembled while making the piece. Spells as prayer, wish, desire, and a way to acknowledge history became a form of writing, storytelling, and new physicality for the films we made as well as for the stage work soon to come.

I had one rehearsal. It was magical. And then Freddie Gray was murdered. I was living in Baltimore at the time, and the ensuing uprising of voices and actions required something different of me. I turned my attention to other stories and listened for other histories. I didn’t come back to the witches until after my move to Arizona and the start of a new life in the desert and in academia.

TWO: It’s the first rehearsal period I spend in my new home at Arizona State University. I am going to bring those pictures to life, laughing to myself, that in doing so, it will be the most pornographic piece I have ever made. More dancers now, and we try all kinds of things. It’s hard because I realize I am wrong. It’s not interesting to bring the pictures to life. Even with all the research I have done, the pictures are already themselves. They don’t need us.

THREE: Sometimes I wonder why I rehearse? Maybe I just want company while figuring things out. Or perhaps I need the performers’ stories in order to find my connection to the material. Or, I need accountability to my own imagination, the people in front of me making it operational. It also seems that once I have those individuals in the space with me, I need to find what the connection is—their connection—between my questions and their lives.

This is a combination of building a beautiful trust but also shoring up self-doubt, which seems always to be lurking about. And maybe, too, it helps drive the purpose of what we are doing. I need them to care about the work, their own growth linked to whatever plots are developing. They test what we are thinking, saying and dancing and, in doing that, they become listeners, makers, and audience all at the same time.

Photo of Paloma McGregor, Leah Cox, and Makeda Roney by Greg Nesbitt • Image Description: Paloma McGregor flying through the rocks and woods of Jacob’s Pillow while Leah Cox and Makeda Roney look on in support. Each performer had to find their place in magic, in lore, and in relationship to each other.

There were several ways this worked in early stages of Wicked Bodies. One was a strange little process we’d engage in at the beginning of every rehearsal. (We would have been apart for months, and coming together meant from all over the country.) We’d stand in our characteristic opening circle and begin our personal check-in with, “I am the Witch of…,” and then we would name ourselves. Such animated joy in rediscovering each other after many months apart! I am the Witch of Old Libraries, or I am the Witch of Mountains and Lakes, or I am in the Witch of In Between. When Keith Thompson named himself that way, at least three more yelled out “I want to be that.” It was such a great way to connect subject to person, moment to history, individual to group.

FOUR: By the time we gather under the auspices of one of our presenting partners, we have a few story lines going. This rehearsal week was going to give us time to see if these had validity and also time to work on production with a team of wonderful designers. I am ruminating on the problem of communicating story in a dance context where even some of my collaborators don’t see a need for saying too much. But my soul craves context, so I write a prologue, in the voice of a young girl, which I hope can set up the piece. Here is part of it:

My mother takes my hand. We walk fast with the wind coming off the lake and our faces getting cold. I try not to smile. It makes my teeth hurt, but it’s hard to contain myself; I hardly ever get touched by my mother, so I hang on to her hand even though I know the way. We are going downtown to an extravagant old theater to see a traveling dance troupe.

We climb up the staircase, narrowing as we move to the very top, where our cheap seats are located. We sit next to a lady who’s wearing horrible perfume. Mother worries the smell will make me sleepy. I don’t know what she is afraid of, since she knows this is my favorite place in the whole history of the world. I open the program book and find the libretto. The pictures in my mind have already taken hold. I am deep in the forest as the lights fade.

This is a Spell, cast by me.

It begins, What makes a witch a witch?

Actually, 18 months into the pandemic and I don’t have this question anymore. I know what makes a witch a witch.

Having your kin murdered by the state can make you a witch.

Surviving extinction can make you a witch.

Navigating the edges between worlds can make you a witch.

Shapeshifting between algorithms can make you a witch.

Holding at least two possibilities in your mind at the same time and being able to act on any one of them in a flash can make you a witch.

Growing up in a witch family can make you a witch.

Claiming that you see the world differently, and bend others towards.

That view can make you a witch.

Claiming that you see the world differently, and not caring if others bend that way or not, can make you a witch.

Standing up in one instance and disappearing in another can make you a witch.

Laughing when the crows cry out can make you a witch.

Walking into a place where you clearly don’t belong and then creating a scene can make you a witch.

Believing in your ancestors, talking to them, moving with them can make you a witch.

Instead of premiering at Jacob’s Pillow, we all go home. Instead of dreaming on a stage, we resort to filmmaking. We have made videos of spells for forgiveness, for fresh air, for love and its generational pull, for naming, for familiars, and a spell for leaving the body when legally killed by the government. We have made rituals for binding breasts, and for finding elsewhere. We have told a story about how the astronomer Johannes Kepler got his mother out of prison for being a witch, but more importantly, suggested that it was her mystical, witch thoughts that propelled him to see the magic of planetary motion. We made a video about James the First, who was responsible for the death of so many witches. He’s the same James whose translation of the Bible is in most hotel rooms. Yes, one man can create so much havoc, death, and misery for so many.

It’s clear to me that the witches can speak to us at any time and place. I am fortunate to be living among them, recognizing their actions and thoughts in my own behavior and dreams. Eventually others will too, as the piece is set to premiere at Sonoma State in the spring of 2022, and by then who knows what the witches will want to say?

(Part Two of this written journey will appear….)

Photo of Ruby Morales by Jenny Gerena • Image Description: Ruby is caught in the middle of a story that she is both telling and listening to. The soundtrack is her grandmother, speaking in Spanish and describing her encounter with a branch that held death, and a trip to the healer in her community. Ruby also turns this story into a spell for how love travels through generations. This photo encapsulates all of that.

Photo of Liz Lerman by Lise Metzger • Image Description: Liz is sitting outside with trees and foliage in the background. She looks to her left with a smile on her face. She is wearing a black blazer, a green blouse, and dark jeans. Her hair is piled high in a bun with a few tendrils escaping.

Liz Lerman is a choreographer, writer, and speaker, and the recipient of a 2002 MacArthur “Genius Grant” and the 2017 Jacob’s Pillow Dance Award. She founded Dance Exchange in 1976 and led it until 2011. Her dance theater works have taken place on stages around the world as well as in shipyards, hospitals, schools, congregations and facilities serving veterans. She has been commissioned by the Kennedy Center, the Lincoln Center, and Harvard University Law School among others. Since the turn of the century, Liz has been collaborating with scientists in research, performance, and pedagogy. Her current projects include building the Atlas of Creative Tools, an online digital commons, and Wicked Bodies, set to premiere in 2022. Liz is a sought-after teacher of Critical Response Process, creative research, the intersection of art and science, and the building of narrative within dance. She is a fellow at both the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and at the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at ASU, and a former fellow at the Robert W. Deutsch Foundation. Liz is currently an Institute Professor at Arizona State University.

Support: https://fundraising.fracturedatlas.org/liz-lerman-projects

Website: https://lizlerman.com/

Disclaimer: This article discusses violence against women. When I use the term “woman,” I am including everyone who chooses to identify as such. I am aware that the patriarchy also affects those who live outside the gender binary in its own specific way, but that is not my story to tell. I see you, and I am also holding space for your liberation. Trigger Warning: Gender violence, Sexual Assault.

Photo by Cruz/Getty Images via BBC Mundo • Image Description: A group of women in Mexico City stand together. They have one fist up in the air and appear to be chanting in protest. They are wearing dark clothes; a woman in the center of the image is wearing just a black bra and has something written on her belly. Some wear green scarves around their necks and blindfolds around their eyes.

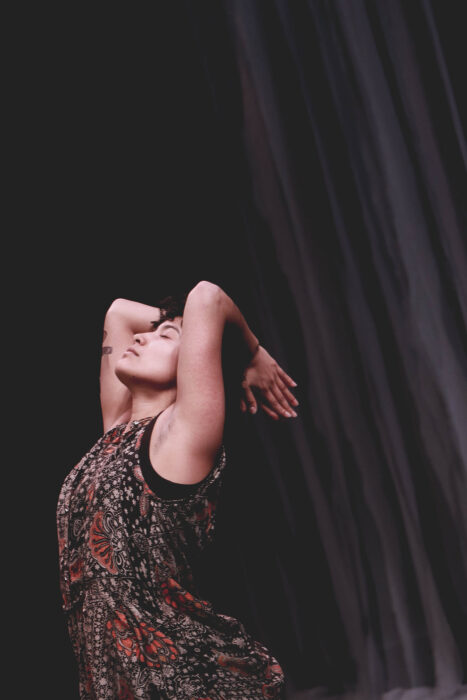

We stand in a circle. One woman teaches the dance. “El Patriarcado es un Juez…” (“Patriarchy is our judge”) she sings while moving side to side to a strong, even beat; she places her hands on her head and does three sit ups. Her forearms proceed to move up and down as she runs in place. We follow and learn the sequence of easy steps. The singing continues: “El violador eres tu (The rapist is you),” we chant as we point front.

This past International Women’s Day, I attended a Latin American-led, feminist protest against the impunity of gender violence and femicide (defined as the “the intentional murder of women because they are women” in 2012 by the World Health Organization). This was the first time I was able to actively participate in the collective fight for female liberation happening in my country since I moved to the US and the first time I got to perform the dance I had seen many times online.

The perfromance titled Un violador en tu camino (A rapist in your path) was originated by Chilean feminist group LASTESIS in 2019 (BBC News). Since then, it has been reproduced in many Latin American countries and become a focus point of feminist protests. The chant/dance, based on texts by the Argentinian anthropologist Rita Segato, is a public communal performance that points out the state, the justice system, the police and the ordinary person as “the rapist” (read: the enablers of rape).

The list of reasons for protesting is not short: from standing up against rape culture, to a fight for abortion rights, to a claim for justice in femicide cases. In Mexico, my home country, an average of 10 women were killed every day in gender motivated crimes last year (New York Times). We are angry, not only at the violence but at the lack of punitive action against our aggressors.

The dance has been reproduced in various forms: in some iterations women wear all black to signify their mourning; in others they wear revealing party clothes or go topless to defy the harassment women often deal with when using revealing clothes. Most times, protesters wear a bandage over their eyes, a reference to the need for justice.

Un violador en tu camino takes on specific steps that have a significance worth learning and describing. The simple, pedestrian movement is used to reference acts of violence against women. For example, the sit-ups make a reference to the Chilean police’s practice of making detained women strip and perform this exercise as a form of punishment (bibiocile.cl). However, this is not the only example of dance being used in protest. Queer and communities of color have historically used dance as a tool for liberation. Think cakewalks, drag ballroom in the late 1960s and ‘70s, Hip Hop and the use of the Electric Slide during Black Lives Matter protests. Most recently, queer dancers in Bogota, Colombia used vogueing to make themselves visible, which is why I argue that it is not the choreography that is revolutionary but the act of dancing in itself.

Let’s take a closer look at how this applies to Un violador en tu camino through three different points. First, the dance-protest calls women of all demographics to participate, and it occurs in public: parks, plazas, streets, educational institutions, and in front of government offices. It is disruptive, uncomfortable and loud. The dancing bodies take up space that they are not supposed to. In an essay titled “Coreopolitics and Coreopolice,” Performance Studies professor André Lepecki claims that the way we are allowed to navigate the world is in itself a choreography: “Movements can only take place in spaces preassigned for “proper” circulation” (20). He examines the ways bodies are choreopoliced and controlled to remain in the “permissible space” (19). Politics and choreography are similar in the sense that they directly deal with how bodies relate to each other in space (Vera, 5).

Photo by Lorena Jaramillo • Image Description: A group of people stand in front of the New York Public Library in Bryant Park. It is dark out, and they are wearing coats and masks. One person holds a Mexican flag. They hold a series of signs that together spell “Ni una menos” (“Not one less”), a catchphrase developed for feminist protests. There are many other illegible signs around them.

I argue the patriarchy is a form of choreopolicing, dictating the ways we move. As the chant says, “El Patriarcado es un Juez” (“Patriarchy is our judge”). Sonya Renee Taylor states in her book The Body is Not an Apology, “we cannot talk about bodies without talking about the systems that govern our bodies” (45). By dancing, we are disrupting the social choreography dictated by the oppressive patriarchal system. Protesters stand where we are not supposed to stand and they dance, not for the male gaze but for themselves: collectively, viscerally, freely; completely defying the gender norms that dictate “how and in what way we can appear in public space” (Butler 34).

Moreover, anyone can be a part of the performance; there are fat bodies, old bodies, disabled bodies, naked bodies. The identities we are taught to hide away are proudly on display, and they are dancing, in a way that can’t be commodified, sold or reproduced and in a space that is not meant for dancing. The dancing protesting body actively stands against the designated social choreography.

While dancing in the middle of Bryant Park, accompanied by a collective of no more than 30 Latin American women, the cops showed up.

“Why are the pigs here, if there are only like ten of us?” yelled one of the women.

In my head I thought “Because only ten is powerful. Ten is too much. Ten is disruptive.”

The disruption is delightfully uncomfortable.

My second point is that performing the movement claims our presence in space. We are here and we deserve care, respect and safety. In her book The Politics of Presence, author Diana Taylor dives into the meaning of being presente and frames it as “an act of political defiance” (46). She goes on to point out how by being present ourselves we are also “showing up with others to fight for those who cannot be there to fight for themselves” (Taylor, 46). Feminist marches, especially those protesting the impunity of femicide, do just that: A cry for justice for our muertas. The movement occurs because of those who cannot be present.

Judith Butler, when speaking about public assembly, highlights the “we” enacted through an assembly of bodies, “plural persisting acting and laying claim to a public sphere by which one has been abandoned” (Butler 59). Similarly, In My Grandmother’s Hands, author Resmaa Menakem writes about the healing of racialized trauma as a collective experience: “mending must be communal as well.” We are not only fighting for ourselves. By dancing in a coordinated group, we are not just claiming our bodies as present, we are claiming the presence of the collective body.

This leads me to my next third point, which is that we cannot be present if we are not embodied. Through dance, we are allowed to center the body in our path to liberation. As Taylor suggests, the “relationships with our bodies are social, political and economic inheritances” (37).

Many of the systems that allow for the oppression of people rely on our disembodiment, a lack of care for our physical being. When speaking about gender violence, our bodies become the main site of violence and policing. Existing in the world as a non-male presenting human is an incredibly violent experience. Our encounters with gender violence, from cat-calling, to rape, to the threat of femicide get stored in the body and translate to the ways in which we navigate this world.

It is through body knowledge that we can explore, investigate and take apart how these systems have impacted us. As Randy Martin writes in the introduction to his book Critical Moves, “dance occurs through forces applied to the body that yields to them, only to generate powers of their own” (1).

I am not suggesting that dance is a substitute for policy change or restorative justice; artistic tools cannot be confused for direct action. However I am framing the use of dance as a tool for embodiment and healing for those whose lives have been marked by the oppressive system of the patriarchy. As Lepecki suggests, dance techniques of freedom, such as TURF, are “technologies for inventing movements of freedom” (22). Resistance begins in the streets, through music, movement, art and through the collective action of those who make themselves present.

Dance remains a tool to reclaim our bodies as ours, to break the social norm of what is allowed and to demand our right to a life free of violence. The dancing body is powerful and defiant. Un violador en tu camino is only one example of dancing women making themselves present through an embodied, disruptive, angry joy for justice.

Additional Resources:

Un violador en tu camino, performed in Santiago, Chile in 2019

Sarah Grace Hafen via Youtube, December 2019

Video learning the dance in Bryant Park, 2021

Lorena Jaramillo, recorded March 2021

Chant Lyrics:

Las Tesis 2019

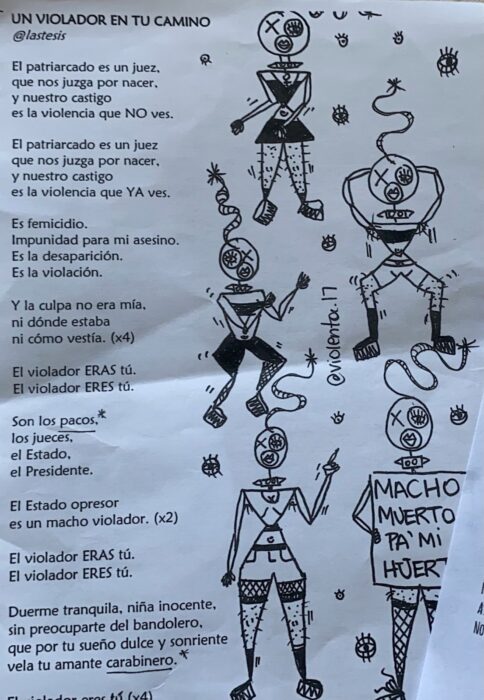

Photo by Lorena Jaramillo/Lyrics by Lastesis/Illustration by @violenta.17 • Image Description: A photo of a flyer distributed in the 2021 Women’s March in New York with the Spanish lyrics to Un violador en tu camino and a series of line drawings depicting people dancing. One of the drawings depicts a person holding a sign that says “macho muerto pa’ mi huerto” (“toxic man dead for my garden”)

Patriarchy is a judge

that judges us for being born,

our punishment

is the violence you don’t see.

Patriarchy is a judge

that judges us for being born,

our punishment

is the violence you now see.

It’s femicide,

Impunity for my killer.

It’s disappearance.

It’s rape.

And it’s not my fault, nor where I was, nor what I wore.

And it’s not my fault, nor where I was, nor what I wore.

And it’s not my fault, nor where I was, nor what I wore.

And it’s not my fault, nor where I was, nor what I wore.

The rapist was you

The rapist is you.

It’s the policemen,

Judges,

The state,

The president

The oppressive state is a rapist man.

The oppressive state is a rapist man.

The oppressive state is a rapist man.

The oppressive state is a rapist man.

The rapist is you.

The rapist is you.

The rapist is you.

The rapist is you.

Sources:

- Abi-Habib, M “A Woman’s March in Mexico City Turns Violent, with at least 81 injured.” The New York Times, 2021. (https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/08/world/americas/mexico-city-womens-day-protest.html)

- Arendt, H. The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press, 1958.

- BBC Mundo. “Un violador en tu camino, de Las Tesis: cómo se convirtió en un himno feminista mundial.” 2019. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2l6SQqdn2Y8)

- Briones, N. “Fue desnudada y obligada a hacer sentadillas.” Biobio Chile, 2019 (https://www.biobiochile.cl/noticias/nacional/chile/2019/10/23/fue-desnudada-y-obligada-a-hacer-sentadillas-39-acciones-por-violencia-uniformada-contra-ninos.shtml)

- Butler, J. Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly. Harvard University Press, 2018.

- Cruz, C. “29 de Noviembre, Ciudad de México.” BBC (https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-50610467)

- Dixon-Gottschild, B. “The Power of Dance as Political Protest.” Dance Magazine, 2020 (https://www.dancemagazine.com/protest-dance-2648441874.html?rebelltitem=1#rebelltitem1)

- El Fariado “‘El violador eres tú’, las feministas cántabras interpretan la coreografía chilena global.” 2019 (https://www.elfaradio.com/2019/12/11/las-feministas-cantabras-se-unen-al-grito-chileno-contra-la-violencia-sexual/)

- Garcia, S “ The Vogueing protesters of Bogota.” The New York Times, 2021. (https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/31/style/colombia-protests-bogota-dancers.html)

- Las Tesis. “Entrevista: La intervención o el problema que plantea es transversal.” Arte al Límite, 2019. (https://www.arteallimite.com/2019/12/12/entrevista-a-las-tesis-la-intervencion-o-el-problema-que-plantea-es-transversal/)

- Lepecki, A. “Choreopolitics and Choreopolice,” The Drama Review 57:4, 2013.

- Marchart, O. “Political Reflections on Choreography, Dance and Protest ” Diaphanes. (https://www.diaphanes.net/titel/dancing-politics-2126)

- Martin, R. Critical Moves: Dance Studies in Theory and Politics. Duke University Press, 1998. pp. 1-27.

- Menakem, R. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway of Mending our Hearts and Bodies. Central Recovery Press, 2017.

- Merelli, A. “Learn the lyrics and dance steps for the Chilean feminist anthem spreading around the world.” Quartz, 2019. (https://qz.com/1758765/chiles-viral-feminist-flash-mob-is-spreading-around-the-world/)

- Taylor, D. ¡Presente! The Politics of Presence. Duke University Press, 2020.

- Taylor, S.R. The Body is not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self Love. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2018.

- Soldati, C. “The rapist is you, the Chilean protest song against gender violence that sparked a global movement.” Lifegate, 2019. (https://www.lifegate.com/the-rapist-is-you-un-violador-en-tu-camino)

- Steptoe, T. “Hip-Hop Continues a Protest Tradition That Dates Back to the Blues.” Yes Magazine, 2020. (https://www.yesmagazine.org/social-justice/2020/08/07/music-blm-movement)

- Van der Kolk, B. The Body Keeps the Score. Penguin Books, 2014.

- World Health Organization “Understanding and Addressing Violence Against Women: Femicide.” 2012. (https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77421/WHO_RHR_12.38_eng.pdf)

Photo of Lorena Jaramillo by Paul Kamau • Image Description: Lorena stands in front of a white background. She turns her back to the camera but looks back at it, serious. She has medium-length, dark wavy hair and light makeup that highlights her brown eyes. She is wearing a low back red dress. The camera only pictures her from the waist up.

Lorena Jaramillo (she/ella) is a Brooklyn based dance and teaching artist. She was born and raised in Mexico City where she began her classical ballet studies. In 2015, she relocated to New York to earn her degree in Dance with a minor in Arts for Communities from Marymount Manhattan College, where she graduated with honors and a gold key in Dance Studies.

Lorena currently dances with dance-theater collective Sydnie L. Mosley Dances and Queen-based contemporary dance company NK&D/A Movement Company, with whom she has performed at the Clark Theater in Lincoln Center and Queensboro Dance Festival, respectively. Other credits include Reza Farkhondeh’s piece “Obscure and Back”, Dani Cole’s movement collective MOBIV, Wise Fruit NYC, Juntos Collective, Semillas Collective, CoopDanza and IndoRican Multicultural Dance Project. As a teaching artist, Lorena works with Bay Ridge Ballet and Amanda Selwyn’s Notes in Motion. As a writer, she was rst published in Rigorous Magazine with her essay “Dancing the Mexican Revolution”. Lorena is committed to the use of dance as a revolutionary practice of joy and to learning and unlearning through movement, conversation and deep listening.

Support: Venmo @Lore-Jaramillo

Website: lorenajaramillodance.com

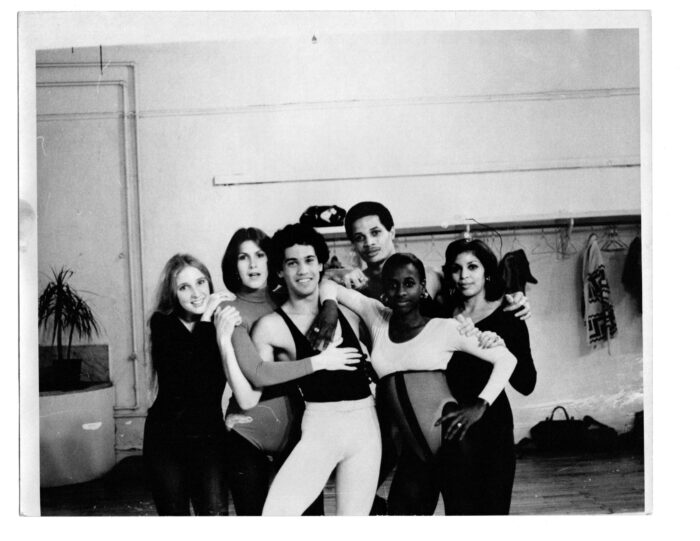

New York City. Late 1970’s to mid-1980’s.

Its history predates its last known address, and its legacy was born years before Louise Roberts, its last director, assumed her role.

Now, grant that I may recall some of my most vivid memories of Clark Center.

There was an elevator. I may have taken it—once! It was toward the back of the building and probably held all of three people. Who knew if it worked? Better yet, was anyone brave enough to find out?

Ignoring the elevator and climbing those old stairs was the first step in the Clark Center experience and the preferred mode of entry to the loud, semi-rundown 2nd floor at 939 Eighth Avenue. There, you were greeted by the sounds of “…and 5, 6, 7, 8” or “and hold, and hold” or conga drums, piano, claves, tambourine, or a clickety-clack shuffle ball change. This was before you even presented yourself at the office desk, cheerfully managed by Joni and Roger and headed by Clark Center’s then director, Louise Roberts. The office was always abuzz with scholarship students and staff— and Louise’s fluffy white dog Max.

Once in the dressing room—small and crowded with bodies bathed in combinations of perspiration, perfume, musk oils or just pure funk–you had to find a corner that wasn’t loaded with street clothes, leotards, shoes, or a body. Once a temporary landing space was identified, you changed into leotards and leg warmers, found a corner to stash your street clothes and left. There was no lollygagging in that tiny space–except there was a woman, almost a daily fixture in the dressing room, who sold dancewear. Apparently, she was also regular at other nearby studios. Hmmm… What was her name?

In Clark Center’s heyday, I think we might have taken diversity for granted. We were such a mixed bag and appreciated that in each other—from office staff, to teachers, accompanists, and students. Added to those different roles, we were diverse in culture, race, age, occupation, background, level of experience, and aspiration. We were scholarship students. We were card-carrying and cash-paying students. We were diehard fans or groupies of favorite teachers. We were hopeful spectators standing in doorways of classes we dared not step into (at least not until we understood the flow and possibly memorized some of the routines.)

There was no discernable rivalry. We knew and respected class leaders and coveted that spot in the second line so we could dance directly behind them. We admired, appreciated, learned, received, and gave back. We were family, and Clark Center was home.

Sometimes, I wish I had made a greater effort to carry a heavier class schedule, but being a scholarship student required a time commitment I didn’t think I could afford. Alas, practical me, I thought my 9-5 was essential to my life. Hellooo! Note to younger self.

Fortunately, I worked around the corner on 57th Street and, most evenings, found myself dashing over to 8th Avenue in time for a quick bite before a 6 o’clock class. Once in class, my world became barre, wooden floors, mirrors, fellow classmates, accompanist, and that particular class’s guru.

Charles Moore was my favorite guru. I started taking his class when Clark Center was at the YWCA on 51st Street and, as an original member of his young company, sometimes taught for him. Frequently, Louise would come to the studio door, give me a look, and without saying a word, let me know that Charles was running late. I-knew-what-to-do, and I loved it. Some of my other teachers included Lucinda Ransome, Jill Albert, Pepsi Bethel, Charles “Cookie” Cook, and Eleanor Harris.

Whether in class; waiting in the hall for class to begin; or watching a class from the doorway, you felt the energy. It was everywhere. Being at Clark Center was like therapy. Correction: it was therapy! The life force that was dance seeped into your pores no matter where you were or what you were doing on that second floor.

If you danced with a Clark Center-based company and rehearsed there after hours, you very likely found yourself leaving the building close to 10PM. Even then, we might extend that energy by heading over to a favorite café on 57th Street for an “after rehearsal” bite to eat. Thank goodness, in those days, riding the subway at midnight wasn’t nearly so dodgy.

I laugh as I remember one late rehearsal in the largest studio, the one overlooking 8th Avenue. The company had the extraordinary opportunity to learn and perform Katherine Dunham’s Shango and, on this particular evening, Charles had invited former Dunham dancers to assist.

It was a difficult and sometimes frustrating rehearsal as the elders pushed, often criticized, and ultimately schooled us. One of them—who will go unnamed—sat in full second position, on the floor, in front of the mirror, barking at us while he wolfed down a huge slice of lemon meringue pie. Yes, I said lemon meringue pie!!!! That night and for some nights after, our “After Clark Center” café gatherings turned into explosions of laughter as we recounted that scene and revelled in the life energy we had experienced. The spirit of Clark Center was all of that—friendly, tough, fulfilling, entertaining, and fun.

Photo by Joan Chanin • Image Description: A group of scholarship students at Clark Center who attended the Japanese Camera convention as models. Left to right: Candice Warwick, Yvonne Saume, Eugene Jerez, Elliott Gillette, Tee Ross, and Geisha Otero.

Today, Clark Center NYC, founded in 2011, is dedicated to preserving legacy. To date, our programming has highlighted distinguished careers of dancers, choreographers, teachers, and company directors who trace their beginnings to Clark Center. We continue to honor these trailblazers by celebrating their contributions to dance, theater, the arts, education, and history. Sometimes, while planning and organizing, we get a little misty-eyed when recalling those who directed the organization to its humble greatness and upon whose shoulders we stand.

As we celebrate the luminaries, however, we also acknowledge the students. Many have graduated to formidable careers in dance, theater, and education while others hold onto cherished memories of Clark Center. When tapped, those memories elicit funny, heartwarming, and personal tales of a long time and of a long place. A few alumni of this extraordinary era shared some reactions with me.

“I cleaned the bathrooms … for the amazing opportunity to take 10 classes each week … all the teachers instilled in me a deep love of black aesthetics …” — Anita

“…I attended classes with Jimmie (Truitt), who made me fall in love with dance like never before.” — Gelia

“… I remember looking up to her (Tee) in awe. Took Thelma & Marjorie Perces, & a guy with the crazy arm routine during tendus! … stood in the doorway watching Fred Benjamin’s class with oooooooo on my face.” — Jacquie

“Watched Beau Parker’s class trying to get the courage to take it.” — Norma

“Unlike other studios or schools … was very diverse, real and raw. Something special oozed from the talent and energy that filled that place. … so grateful to have had that experience. ❤️” — Shirin

“The studios literally smelled of dance—the sweat and tears, the discipline and the triumphs, and the power and the magic of movement was almost palpable.

“But the thing that moves me the most from those special times at Clark Center is being touched, embraced, and empowered by the love of dance that not only was shared by the masterful teachers … but also was the beating heart of Clark Center itself. Magical moments in a magical place forever cherished and fondly remembered!” — Bryan

“After taking class I would marvel at the joy and sweat in Loremil Machado’s class. I would chuckle at Joel Dabin sitting on a chair in front of his class, with a cigarette, teaching ballet.” — Lisa

“… Louise’s dog Max was friendly to all but drew the line at drummers carrying conga drums. He would bark furiously but was their best friend when the drum was put down. Joel Dabin also brought a dog to class. It was a tiny Yorkie who would stay in his bag and just come out when the students applauded at the end of class.” — Joni

Clark Center is all about the students, the community, the spirit, the stories. Oh, the stories!

One day many years ago, while still working in the area, and long after Clark Center closed, a disheveled homeless man approached me on the corner of 57th and Broadway. In typical New York “I’m-in-a-hurry-don’t-bother-me” style, I ignored him. Then … what?!? He called my name?!? What in the 57th -Street-and-Broadway-hell is this?? He said “You used to dance with Charles Moore. I remember you from Clark Center.”

He could have stopped at Charles Moore. He had my complete attention and could have knocked me over with a feather. Besides teaching me a lesson in compassion, here was an in-your-face reminder of the longevity of Clark Center fellowship. PS: The story ends with a donation to his personal cause and the recommendation of a nearby food pantry.

So, you see, Clark Center was more than a dance school. It was a community, a safe haven, a story-maker and, yes, those creaky stairs. Most of all, Clark Center is the birthplace and incubator of extraordinary talent, a lifetime of rich memories, and treasured friendships that span the globe.

Clark Center NYC plans to bring together a panel of alumni to elaborate and share more stories. Visit our website or our Facebook page, Remembering Clark Center, for updates and information.

Photo by Yazmany Arboleda • Image Description: A photo of Ramona Candy smiling with her eyes closed. She stands in front of a gray background. She is wearing dark brown glasses, a coral-colored shirt, colorful earrings, and red lipstick. Her hair is cropped close to her head. Place: Future Historical Society Planning Meeting Date: April 2019

Ramona Candy: I describe myself as motivational artist, curator, arts administrator, accidental historian, occasional blogger, and dancer. Inspired by my Caribbean heritage, growing up in Brooklyn and my long performing career with the Charles Moore Dance Theater, my artwork is inspired by Sankofa (“to go back and retrieve”). Whether it’s personal memory or collective experience, my work is lled with nostalgia, history, community, and cultural appreciation. In my most recent series of collaged portraits (Our History, Our Pride), I identify figures in Black history and give them voice, through exhibition and workshop. I have shown in galleries throughout the tri-state area and am in private and public collections including Art in Embassies (Dili Timor-Leste), NYC Health and Hospitals Corporation, Memorial Sloan Kettering. My art was the featured art for BAM’s DanceAfrica 2010, and the International African Arts Festival in 2006 and can be seen on several television sets, and the feature film, Black Nativity.

Currently, I am Director of the Council for the Arts at St. Joseph’s College, Brooklyn where I enjoy bringing together community and artists. I have presented art-making workshops for Safe Horizons, The United Nations International School, The Brooklyn Public Library and Myrtle Avenue Brooklyn Partnership. Once a dancer, always a dancer, I occasionally lead dance workshops, and sit on the board of Clark Center NYC, a dance legacy project. I am a founding member of the Future Historical Society, an oral history/art making project at BRIC.

I credit my late mom, Carmelite Candy – a resourceful, creative single mother of four – for everything!

Website: https://linktr.ee/ramonacandy

Photo of Eva Yaa Asantewaa by Scott Shaw • Image description: Eva Yaa Asantewaa (she/her) faces the camera against a teal-colored background. She is a Black woman with medium-brown skin, dark-brown eyes, and very short grey hair. She’s wearing a multicolored, sleeveless dress with a scoop neckline and dangling earrings made of plastic feather-like pendants and pearls. Wearing cranberry-red lipstick, she’s smiling warmly, her head tilted slightly towards her left shoulder.

Eva Yaa Asantewaa (pronouns: she/her) is Gibney’s Senior Director of Curation as well as Editorial Director for Imagining: A Gibney Journal. She won the 2017 Bessie Award for Outstanding Service to the Field of Dance as a veteran writer, curator and community educator. Since 1976, she has contributed writing on dance to Dance Magazine, The Village Voice, SoHo Weekly News, Gay City News, The Dance Enthusiast, Time Out New York and other publications and interviewed dance artists and advocates as host of two podcasts, Body and Soul and Serious Moonlight. She blogs on the arts, with dance as a specialty, for InfiniteBody.

Ms. Yaa Asantewaa joined the curatorial team for Danspace Project’s Platform 2016: Lost and Found and created the skeleton architecture, or the future of our worlds, an evening of group improvisation featuring 21 Black women and gender-nonconforming performers. Her cast was awarded a 2017 Bessie for Outstanding Performer. In 2018, Queer|Art named one of its awards in her honor, and Detroit-based choreographer Jennifer Harge won the first Eva Yaa Asantewaa Grant for Queer Women(+) Dance Artists. In 2019, Yaa Asantewaa was a recipient of a BAX Arts & Artists in Progress Award. She is a member of the Dance/NYC Symposium Committee and the founder of Black Curators in Dance and Performance.

A native New Yorker of Black Caribbean heritage, Eva makes her home in the East Village with her wife, Deborah. Sadly, their best-cat-ever Crystal traveled over the Rainbow Bridge on February 18, 2021.

Photo of Monica Nyenkan by Jakob Tillman • Image Description: Monica Nyenkan is the daughter of African immigrants. She has dark brown eyes and hair. In this photo, her hair has two-strand twists.

Monica Nyenkan is a Black queer community organizer and arts administrator hailing from Charlotte, NC. She graduated from Marymount Manhattan College, with a Bachelors in Interdisciplinary Studies. Currently based in Brooklyn, NY, her artistic and administrative work focuses on creating equitable solutions with and for historically marginalized communities in order to make art more accessible. In her free time, Monica loves to watch horror films and share meals with her friends and family. A fan of educator and historian Robin Kelley, Monica firmly believes the decolonization of our imaginations will help facilitate a more radical and inclusive way of living.

DISCLAIMER: Opinions expressed in Imagining: A Gibney Journal are the writers’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views, strategies or opinions of Gibney.