Imagining

A Gibney Journal

Issue 6

Letter from the editor

Oh, how I wish I had a dollar for every time…

No, let me start over.

I wish Gibney had a million dollars for every time I sat down to write one of these Letters to the Editor, two months in advance of an issue’s publication, and thought, “Will these words still have relevance when Imagining’s readers finally get to see them?”

What a time this has been since Imagining: A Gibney Journal first gathered itself in the middle of 2020 and, last September, mounted the digital stage! It seems every week—no, every day, every minute—has brought more of the unexpected, the challenging, the just plain unbelievable.

So, welcome to our second year, loyal reader! We made it! And so did you!

This is the point at which it’s customary to start prognosticating and crowing about how fantastic the next sweep of months will be. And maybe they will be! Months filled with your pick of high-paying arts jobs; the grant money you never thought you’d get—doubled; exciting dates that might yet turn into love everlasting. My witchy crystal ball—and, let me assure you, I do have one at arm’s reach—tells me your dreams will come true!

Truth is, we’ve learned these 2020s always have something wriggly up their sleeves. And have you seen those sleeves? Huge!

So, I figure we have to be way craftier than them, stay vigilant, study up, rest up, take loving care of ourselves and our peeps. That last part, especially.

What I can promise you, Imagining-wise, is that you’re our peeps, and we’ll continue to take care of you with good reads from new writers. After barely a break, we’re back with essays from Nehemoyia Young, Sarah Cecilia Bukowski, Lea Marshall, and Joy-Marie Thompson—all of whom have learned something authentic and transformative at the university of the body.

I’ll leave you, for now, with encouragement from the life and work of 90-year-old visual artist Faith Ringgold (CBS Sunday Morning, July 11, 2021). Don’t let the system shut you up or shut you out. Look around until you find that door you can bust through.

Yeah, we’re going in!

Eva Yaa Asantewaa

Senior Director of Curation

Editorial Director, Imagining: A Gibney Journal

Photo of Eva Yaa Asantewaa by Scott Shaw • Image description: Eva Yaa Asantewaa (she/her) faces the camera against a teal-colored background. She is a Black woman with medium-brown skin, dark-brown eyes, and very short grey hair. She’s wearing a multicolored, sleeveless dress with a scoop neckline and dangling earrings made of plastic feather-like pendants and pearls. Wearing cranberry-red lipstick, she’s smiling warmly, her head tilted slightly towards her left shoulder.

Why have our museums become such a “culture wars” flashpoint in a way that concert dance has not?

Maybe, by presenting a long-term or permanent record of things, cultures and histories, museums have built greater consequence in the American imagination, whereas the evanescence of concert dance in time and the ambivalence with which it is often received by mainstream culture and consumerism put it out of sight and mind.

Many of us remember being taken on–and possibly enjoying—trips to visual arts and natural science museums when we were school kids or attending with family. An emotional investment might linger. And, yes, many of us do fondly recall our first encounters with Alvin Ailey’s Revelations or The Nutcracker—or, as in my case, way too many years ago, the Rockettes—and that enchantment might have stayed with us. But museums give us an official measure of the worth of our stories, icons, ideals, identities; they represent us—well, maybe. But we grow accustomed to viewing museums as arbiters and archives of what’s most important for each and all of us to know, value, and safeguard.

I mention all of this to direct you to one of the first things that caught my attention as I began to read curator Laura Raicovich’s Culture Strike: Art and Museums in An Age of Protest, published this past June. She clearly has not forgotten how deeply embedded museums were in her experience of youth, in her curiosity, imagination and happiness. A visceral feeling arises—for writer, for reader—that speaks to the authenticity and continuing aliveness of these memories. And it is out of this feeling that Raicovich identifies how love makes us–and makes her–fight hard for whatever we decide museums should be.

Most recently interim director of the Leslie Lohman Museum of Art, Raicovich is perhaps best known for her time as President and Executive Director of the Queens Museum, a post she cherished and reluctantly left amid mounting controversy when Israeli officials arranged to use the museum for a reenactment of the 1947 United Nations vote partitioning Palestine. (See this Hyperallergic news item from August 2017.) She is a good instigator for a book sharply questioning the belief that museums are–and should be–silent, neutral repositories. Her book recounts numerous dustups contradicting that supposed innocent neutrality.

Whose hands are pristine? Not when arts institutions craft woke-sounding slogans and statements while upholding white supremacy every single day. When museums take funding from the creators of OxyContin or from the murderers of a journalist. When a white-led museum declares itself more capable of caring for and interpreting artifacts stolen from non-white cultures than the institutions and experts in those same cultures. When a celebrated exhibition about Harlem shows no work by Black artists. When museum boards welcome a member whose business trades in tear gas used against protestors. When a white artist presumes to use iconic images of Black or Indigenous trauma for his or her own creative purposes. Writing with utmost clarity for a readership beyond academia, Raicovich relates the long history of these types of problematic scenarios and relationships.

She also weaves in hopeful prompts for reversing the historical violence preserved and perpetuated by cultural institutions. Central to her argument is a critique of the notion that museums, first established by white European and Euro-American gentry, represent some “universal” good. Like any claim to neutrality, this masks the continuing fact of white dominance in the upper tiers of arts administration and curation.

Although Raicovich does not deal with issues faced by dance and movement-based artists navigating the museum system—or, for that matter, our own dance institutions—it will be useful for these arts workers to read her accounts of pitfalls and solutions and consider how her ideas might be applied to problems in our own field.

Every other year, I teach a course in Dance Criticism which inevitably leads me into a crisis of uncertainty. My students and I conduct power analyses, interrogate bias, and unpack existential questions about the form—who is criticism for? Who does it serve, and how? Dance critics are not supposed to be “objective,” of course, since they are expressing an opinion. Right? But how transparent are critics about their subjective stance? How transparent are the media outlets that publish them? Who even reads criticism, and why? And of course, How do we write it?

I have come to value the questions, which remain more constant than the answers, and the openness and thoughtfulness they demand. My reading and thinking over many years now has led me to others asking similar questions in different disciplines. It was not until reading Lewis Raven Wallace’s 2019 book, The View From Somewhere: Undoing the Myth of Journalistic Objectivity, however, that asking such questions made lightning-clear connections for me that interpenetrate among dance, photography, literary writing, visual art, forest ecology, medicine—most areas of knowledge, in fact, that shape the ways in which people move through and relate to the world. What does the end of journalistic objectivity have to do with dancers and trees? I think it will help them survive.

In 2017, Wallace, then employed at American Public Media’s radio show Marketplace, wrote a post on his blog titled “Objectivity Is Dead, and I’m OK with It.” In The View From Somewhere, he describes the post:

“I wrote about my experience as a transgender journalist, never neutral on the subject of my own humanity and rights, even as they were being debated in ‘both sides’ journalism….I knew there was a long history of ‘objectivity’ changing to accommodate the shifting status quo, and I wanted a journalism that rigorously pursued verifiable facts while claiming a moral stance, fighting back against racism and authoritarianism.” (p. 2)

Citing concerns that the post crossed the line from journalism into activism, Marketplace wanted him to take it down. Wallace initially did before changing his mind, reposting, and getting fired.

Writing The View From Somewhere in the wake of that experience, Wallace draws on historical and contemporary voices, events, and movements to deepen his own and readers’ understanding of the fluid nature of journalistic “objectivity.” In discussing media coverage of the Vietnam War, Anita Hill, the AIDS crisis, and other major events, Wallace’s insightful analysis reveals “objectivity” as a tool used less in the service of truth than of gatekeeping.

He outlines the paradox of how writers from marginalized communities who manage to land jobs with mainstream media are often barred from covering those very communities. But, as his research revealed, “gay journalists were the ones who made more room for stories about gay people and AIDS; Black anti-lynching activists were the leaders in telling stories about the terrors of Jim Crow laws; #BlackLivesMatter activists were the ones who created an opening for better reporting on police killings; and transgender writers have been leading the debate over trans issues for two decades, in spite of our exclusion from much of the supposedly ‘objective’ discussions about our lives. A wonderful part of the end of ‘objectivity’ is that oppressed people’s voices can no longer be excluded on the false pretence that we are biased in favor of our own humanity, that we are too close to the story.” (p. 14)

In tracing and rigorously questioning this history, Wallace sharpens our ability to question “objectivity” and outlines a framework for journalistic practice that leaves it behind in favor of more honest and inclusive values such as curiosity, compassion, and the ability to balance multiple truths at once.

As these values surfaced in my reading of the book, they illuminated connections to other texts questioning similar ideas such as “the universal,” abstraction, even the scientific method. Across these conversations, the “certainties”—which emerge, of course, from a white, western hegemonic conceptualization of the world—engender rage and confusion, disconnection, and dissociation in people whose identities do not match the [white, male, cisgender, able-bodied] background. In his essay, “Is Abstraction For White People?,” language fails Miguel Gutierrez: “Who has the right not to explain themselves? The people who don’t have to. The ones whose subjectivities have been naturalized. It enrages me. No, it confuses me. I’m all for being confused, for searching, for having to do a bit of work. But the absence of explanation is somehow … somehow … somehow what?”

In The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race and the Life of the Mind, editors Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda elaborate by critiquing the idea of the “universal” so often deployed in literature and criticism: “If we continue to think of the ‘universal’ as better-than,… we will always discount writing that doesn’t look universal because it accounts for race or some other demeaned category. The universal is a fantasy. But we are captive, still, to a sensibility that champions the universal while simultaneously defining the universal, still, as white. …To say this book by a writer of color is great because it transcends its particularity to say something ‘human’ (and we’ve all read that review, maybe even written it ourselves) is to reveal the racist underpinning quite clearly: such a claim begins from the stance that people of color are not human, only achieve the human in certain circumstances.”

Rankine and Loffreda offer an alternative vision, one that resonates with Wallace’s in its value of the writer’s subjective experience of their identity. “…We know there is no language that is not loaded. But we could try to say, for example, not that good writing is good because it achieves the universal, but perhaps instead that in the presence of good writing a reader is given something to know. Something is brought into being that might otherwise not be known, something is doubly witnessed.”

This idea of being given “something to know” resonates with Susie Linfield’s 2010 book, The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence, in which she considers how to engage with photographs of horrific acts. “…We can use the photographs’ ambiguities as a starting point of discovery: by connecting these photographs to the world outside their frames, they begin to live and breathe more fully. So do we. Instead of approaching these images as static objects that we either naively accept or scornfully reject, we might see them as part of a process—the beginning of a dialogue, the start of an investigation – into which we thoughtfully, consciously enter.” (pp. 29-30)

This idea of dialogue, of thoughtfulness and consciousness on the part of the viewer rather than passivity, offers a vision of collaboration between makers, viewers, and critics as well, which implies accountability and rigor along with curiosity and compassion. Questions merge into answers, pointing the way toward more open, radical ways of imagining and being together amidst difficulty and celebration.

As these writers emphasize, we’re living in an age which demands, more and more, that all of us recognize the limitations if not the outright harm and destruction that the “objective” view can cause, mask, or make way for. Forest ecologist Suzanne Simard, in Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest (2021), offers a heartbreaking account of how her research into how trees communicate and share resources, how forests actually thrive, was dismissed in its early years by foresters and policymakers. She explains the role of objectivity in that dismissal:

“I’d been taught in the university to take apart the ecosystem, to reduce it into its parts, to study the trees and plants and soils in isolation, so that I could look at the forest objectively. This dissection, this control and categorization and cauterization, were supposed to bring clarity, credibility, and validation to any findings. …I soon learned that it was almost impossible for a study of the diversity and connectivity of a whole ecosystem to get into print. … Somehow … I have come full circle to stumble onto some of the indigenous ideals: Diversity matters. And everything in the universe is connected—between the forests and prairies, the land and the water, the sky and the soil, the spirits and the living, the people and all other creatures.” (p. 283)

In their questioning of “objectivity,” or abstraction, or the “universal,” all of these writers arrive at similar conclusions highlighting the value of diversity, connection, compassion, and curiosity in the face of uncertainty. Wallace notes, “One of my deepest beliefs, one of the practices I value the most, is admitting what we don’t know—allowing our minds to swim in the questions, to be submerged. If autocracy and racism and fake news foreclose imagination and colonize doubt, I believe curiosity lies at the center of a framework for resistance that cultivates imagination, that cultivates the skill of living in questions.” (p. 213)

Back in Dance Criticism class, we talk about how the very role of a critic has historically been not to ask questions but to hand down answers about the quality of a work or even the worth of an artist. Once we have dismantled this idea and pushed ourselves deep into uncertainty, I ask the students to create a list of guidelines for how to write about dance responsibly. Their list can invariably apply to most disciplines: Do your research; Question your biases and assumptions; Acknowledge the work that goes into making art; Honor the experience of the audience around you; Approach everything with a basic level of respect. These guidelines reveal how Wallace’s idea of living in the questions, as an antidote to “objectivity,” implies a profound and moving humility in the face of everything we don’t know—about a dance, about a death, about the forest, and about ourselves.

Nothing happens in a vacuum. Many thanks to Chioke I’anson, who recorded and uploaded the audio recording of Lea’s essay.

Works cited:

Gutierrez, Miguel. “Does Abstraction Belong to White People?” BOMB Magazine. November 7, 2018. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/miguel-gutierrez-1/

Linfield, Susie. The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago, 2010.

Loffreda, Beth and Rankine, Claudia. “Introduction.” The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind, edited by Loffred and Rankine. Fence Books. Albany, NY, 2015.

Simard, Suzanne. Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest. Alfred A. Knopf. New York, 2021.

Wallace, Lewis Raven. The View From Somewhere: Undoing the Myth of Journalistic Objectivity. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago, 2019.

Photo of Lea Marshall by Virginia Commonwealth University • Image description: Lea Marshall sits in front of a gray backdrop. She wears a smile and a teal-colored top. Her long brown hair is pulled into a braid.

Lea Marshall is a writer and educator whose work has appeared in The Atlantic, Dance Magazine, Dance Teacher, Linebreak, Unsplendid, Hayden’s Ferry Review, B O D Y, Diode Poetry Journal, Thrush Poetry Journal, Broad Street Magazine, and elsewhere. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from Virginia Commonwealth University, where she is also Associate Chair of the Department of Dance & Choreography. She is currently pursuing studies in Nonviolent Communication and in end-of-life doula work.

Support: Venmo @Lea-Marshall-1

Website: www.inknode.com/leamarshall

I was eight years old when I committed to my tunnel vision of living in New York City; specifically, paying my bills by being a performer. I followed the set narrative for young, aspiring performers; that sacrifice is needed and expected to pursue the competitive field of performing arts. I missed birthday parties, reunions and playdates, which turned into me struggling to maintain relationships in spaces where I was the one Black person, or one of the few. I felt this most often in dance studios.

By the time COVID-19 hit the shores of the US I had gained my dream. Then, quickly, in the space of two months, I lost it. On the day my show closed, I moved back home to my small town. I was devastated and felt defeated. In the following months, I lost my income and friendships. Family members suddenly passed away, and my identity—which was closely knitted to being a dancer—was in flux. I admit, in the context of the public health crisis and what was going on for others, my reactions were probably dramatic. But I was changing.

Dance was no longer a priority for me. My mental health, living family, and committed friendships were far more important. But, my mental health was also at an all-time low.

Once dance made me feel empowered and safe. But I felt sad and disembodied. I practically stopped moving—let alone dancing–for about six months. At most, I taught a few virtual classes here and there. That’s a long time away for someone who had been practicing dance nonstop since age four.

There were other reasons unbeknownst to me at the time, that explained this disembodiment. The pandemic pause gave me time to find these reasons, and eventually, find movement again with new intentions. But, of course, I first had to surrender into grief.

Starting in April 2020, I began therapy again and slowly worked up to discovering that dance absolutely has the capacity to heal. When treated as more than a vessel to produce shapes and perform, the body can find home again.

…

I was learning about stress, and my inability to determine what my boundaries were—and how to state them clearly—created more stress for me. A recovering “people pleaser,” I burdened myself with relationships and jobs that were incompatible with my spirit.

My therapist—who I will call Alex—told me I was like a hamster running in a wheel and literally showed me a card with the image of sweaty person running in a hamster wheel! It was humorous but, seeing myself in it, I was turned off. I didn’t want to look like that anymore.

I made a commitment to prioritize myself. I’d say no or yes when I really meant it. I’d treat myself with a latte or get a manicure. I’d text a friend back when I wanted to, not when I was expected to do so. I’d stop always reaching out to folks first. I’d choose to yell when I was upset and cry when I felt like it.

Then I began to work out and run (literally) on occasion. I started doing a style called Animal Flow, and other ground-based techniques that encourage my muscles to burn. I appreciated my skin stretching and succumbing to my heat produced as my legs pumped and arms pushed through the floor. It’s cathartic to push my body through movement with the only goal of waiting for and welcoming sweat. I wasn’t dancing yet, but I felt a release that was waiting to burst out. I got off the hamster wheel.

…

I’m perched on my seat, talking to Alex through my screen again, detailing how distraught and disembodied I’ve been feeling.

“I feel like I’m…”

I started to push my hands in front of me, stopping before my elbows could fully straighten as if something prevented me from going further. Alex noticed.

“Let’s investigate that movement that you’re doing. Would you be willing to do that? That pushing movement … what are you pushing?”

“It feels like I’m…pushing a brick wall…”

Alex guided me into a short meditation and body scan that lowered my heart rate. I found myself squeezed into the small space that was between the side of my bed and my literal brick wall. They suggested various interactions with the wall.

“What happens when you press as hard as you can against the wall with your hands? Your legs? What if you release into the brick wall? Are you able to support yourself like that?”

The answer, I found, was yes. When I allow myself to have the option to release my weight into the brick wall, that wall becomes a malleable surface capable of working with my body. Acceptance and release of self is scary. A flood of emotions filled the pool of my body when I gave that brick wall my feelings and released into it. It’s very different from pushing and laboring to try to shove a heavy wall forward.

I was the obstacle in my life. I felt I deserved the punishment of unnecessary struggle. I felt that to grow, I would need to “get over” or “around” myself. But, really, I just needed to accept myself and work with who I am at any given moment.

…

At my summer job, I work as a direct support professional (DSP), caring for clients with physical and intellectual disabilities, from ages 8 to more than 80. They will need basic care and accommodations for the rest of their lives.

After lunch, Caitlin, a young woman in her 30s with a severe seizure disorder, needs to be changed into a new adult diaper. To transfer her from the dining table to her room I need to either transport her via wheelchair or assist in walking her.

Her mother wants her to walk a bit more while she can, so I opt to walk. I undo her seat belt and bend down in front of her. I put my left foot in between her feet that barely touch the floor. I place the inside of my elbows into the space in her armpits for security and gently coax her to standing. I smoothly and gently transition and shift to be behind her. I place my elbows under her armpits again and my chest on her back, then cross my hands to support her upper body. I bend my knees behind her to place the front of my hips on her butt for extra support. As I slowly walk, my shifting helps her legs shift into motion.

All of these actions could be considered just doing my job. Instead, I see them as a dance—a duet—with Caitlin following my lead.

…

During the height of the pandemic, I consumed hours of entertainment on TikTok, chuckling and laughing out loud. Today, I find myself swiping to the face of a person—face directly in the camera—talking about grief and the growth it takes to surrender into it.

“Is there a story…in your brain that you’re just trying to get the pieces to fit?

“I want to invite you to the possibility that this is actually grief. Your grief. Grief and fear and loss are some of the biggest and hardest feelings for people to tolerate.

“One of the most effective ways to [repress them] is by intellectualizing them. It’s okay to set down the story.”

They continued to speak about the action of surrendering. A quick Google search of it’s definition would tell you it’s to “abandon oneself entirely… to give in… yield.” I say it means to give up. That phrase give up feels like it could be painted in a negative light but I chose to spin it.

By this time, I’ve been consistently taking antidepressants and stimulants to manage my anxiety and overwhelming symptoms of ADHD, and they’re working for me. For years, I never thought I’d take medication for my mental health because it felt like giving up. The decision to take them took some surrenderance to my situation: that I needed help and pills can help alleviate some stress. Still in my bathroom, I got up and started dancing with the word surrender etched into my mind. I let the word travel through my body. As my knees bent, I allowed my pelvis to follow suit at the joints. I bent my head forward, giving in to the effort to let go. I reached up to grab hold of something intangible, elbows bending, hands yielding to another choice. Chest and head lifting upwards, I strived to see the narrative I’d made up and decided to graciously push it away. Now I am dancing!

Currently, I don’t consider myself to be a dancer, nor a performer, but, rather, someone who, when available, makes art. Right now dance is the medium. Unlike when I was younger, I no longer need my identity to be attached to my profession. Calling myself a dancer does not give me space to be fluid in my choices.

I can dance in my room…

I can dance in my room and feel fine that no one is watching.

I can study to be a therapist.

I can get paid equitably to dance.

I can choreograph.

I can teach.

I can love.

I can be loved.

An Offering

This is what movement is made of. Movement is never made in a vacuum. It comes from the emotions and actions of living- at least a strong attempt at living- a life. The good, the bad, the ugly all included.

Picture this in your mind’s eye: two naked babies run around on a sunny beach. They let the ocean’s water tickle their toes. They are laughing, they are touching their bodies and they are enjoying each other.

Take a moment to hold this image in your mind’s eye and notice how your body feels. Stay with that feeling for another moment.

Did you get tense?

Did your body compress into itself with your heart rate getting faster?

Did you want to turn away from that image?

Did you want to shrink?

Did you want to cry?

Or did you loosen up?

Did you smile?

Did you feel warm?

Did you want to extend your arms towards that image of the sun, twirling in the way you did as a child?

Did you feel like you could expand?

Photo of Joy-Marie Thompson by Kitoko Chargois • Image Description: Joy-Marie Thompson, a brown skin Black woman with a bald head, is covered in a ripped black mesh body stocking. Her arms, also contained in the bodystocking, cross her torso and head. Her eyes look through the mesh into the viewer. She is standing amongst of collection of old and oversized tires.

Joy-Marie Thompson is a dancer, choreographer, creative director, and certified ANIMAL FLOW©* instructor from Pittsburgh, PA who is making work that is rooted in the curiosity, spirit, and advocacy of our bodies.

Support: @joymariethompson

Website: joymariethompson.com

It’s no secret that dancers’ lives have changed profoundly over the past year and a half. We were shattered, we despaired, we persevered, and we danced however and wherever we could. Now it seems we are opening up tentatively into something resembling the Before Times, only everything’s changed. Or has it? We’ve been eager to “get back to it” for some time now, though there’s no going back exactly. Strangely, I find myself lingering in a space of pensive pause, rolling around in my head the hows and whys of our jubilant resurgence.

And there’s one little piece of this puzzle that’s like a wiggly tooth in my mind. It’s to do with something ubiquitous and seemingly commonplace, something that quite literally holds us together: dancing in unison.

So, why unison? Well for starters, many dancers haven’t really danced together in a while. Together in time, together in space, together in step and rhythm and, perhaps most of all, together in breath. We’ve been isolated like never before in the practice and performance of our deeply communal art form, with the proximity, touch, and breath of others causing anxiety, fear, and rejection. We’ve experienced the frustrations of attempting (and in my case, abandoning) unison on Zoom, so strangely disoriented and disembodied. We’re navigating the steep curve to recover physical skills and mental faculties patterned in our bones, muscles, and memories. And we’re all going through this together.

As we return to sharing space and movement together, I’m wondering how we might interrogate unison–and the process of getting to unison—in ways that reflect our individual experiences and social identities. How can we balance the individual and the collective in the creative process by tapping into a deeper sense of empathy for our essentially social, vulnerable, human selves? What does it mean to dive into unison again after this collective trauma of isolation and loneliness?

Let me make a distinction here. Dancing in unison ≠ dancing together. In fact, these two concepts can sometimes seem almost diametrically opposed. Dancing together is a fact of human nature, more ancient than memory. Dancing together is a part of ritual, community, sacrament; it’s an almost animal instinct, one we feel stirred by natural phenomena like the fluidly shifting morphologies of a murmuration of birds at dusk. Dancing together is an emergent function of the collective, of individual beings driven to move by a shared force, be it music or fire or rain or worship in any form: healing, mourning, celebration, exultation. When we dance together, we are human together.

Unison is something else entirely: an expectation of uniformity, a feat of skill, a repetition of a prescribed norm, a choreographic trope. And while dancing in unison certainly taps into the instinct to find collective identity in dancing together, I’ve found that when rigidly codified it can have the opposite effect: unison can distort our nature and train the instinct right out of us.

So what is it that so attracts us to unison in dance? Well, there’s something powerful about seeing a group of bodies moving in lockstep. It’s mesmerizing to watch a landscape of limbs amplified in kaleidoscopic super-stereo: think “Thriller,” “Rhythm Nation,” drumlines, step teams, or the Rockettes. Choreographically, unison is a grounding base from which to depart and return, a structure to puzzle and repuzzle, a pattern to break apart and reconstruct. Unison accomplishes something that would be impossible alone. And as a dancer, there’s something truly profound about being inside the flow, tapping into a collective kinesthetic ESP and a drive to move with purposeful precision toward a goal larger than yourself. In practice, unfortunately, it’s rarely that romantic.

There’s a dark side to unison: the authoritarian oppression of its uniformity, the erasure of individual identity and negation of difference in its hunger for sameness, the tyranny and absolutism of its demands. Think of the doll-like anonymity of early 20th-century kicklines—it’s no coincidence that the rise of industry paralleled the emergence of new media and the mechanization of bodies—think of neat rows of disciplined ballerinas or fields of dancing bodies in mass spectacle propaganda demonstrations. While dancing together is human nature, dancing in unison can be downright unnatural.

In the context of my career primarily grounded in ballet, I’ve found that unison is too often achieved through practices and processes driven by the authoritarian absolutes of right and wrong. The demands of a flawless choreographic unison require hours of drills punctuated by false starts, frustration, accusations, and blame. Divergence is marked as error and trained out by rote. I still have slow-motion nightmares about the time I sent an enormous grand battement sailing into the air one whole count early in the naked chaos of the iconic Balanchine/Stravinsky ballet Agon. And in ballet specifically, as in many other dance forms, unison is demanded not just in our movement, but in the very shape of our bodies and tenor of our voices. This speaks volumes of our aesthetic priorities, rehearsal cultures, and the cult of the choreographer, not to mention the white Eurocentric dominance that continues to plague ballet. And to what effect? Unison has the power to be shocking, grounding, revelatory, and truly beautiful, but when it’s ineffectively deployed it can fall flat: restrictive, numbing, mindless, and downright boring.

Don’t get me wrong here. I’m not against unison, though I’m actively questioning its place and purpose in our culture. I’m not suggesting a movement toward radical individualism. Far from it. Radical individualism can be as tedious a trope as tired, pedantic unison. I’m just tonguing this wiggly tooth here, pushing gently this way and that. Sooner or later it’ll fall out and something newer and stronger will grow in its place.

I find this all coming up for me in the contemplative, sometimes painful space opened by the pandemic. Since last March, we as dancers have been challenged in ways we never could have imagined. We’ve trained (and sometimes performed) in our kitchens, in our living rooms, in little stolen alcoves crowded with the objects and encumbrances of our everyday lives. Maybe we’ve danced outside, negotiating new relationships to nature and the elements. Maybe we’ve danced in studios with masks on and invisible six-foot force fields around us. If we’re lucky, maybe we’ve had permission to touch someone. It’s a strange new world, and the uncertainty of it all can feel profoundly unsettling.

For me, this loneliness has been challenging, but also deeply reflective and strangely generative. Early on I noticed a curious new feeling in my body. For the first time in my long dancing life, I felt my body was truly my own. No one was telling me what to do with my body. No one was expecting anything of my body. No one was viewing my body as a commodity or an exhibition. I was nobody’s vessel, nobody’s tool, nobody’s project.

This feeling was oddly disorienting and, once I got the hang of it, immensely liberating. Every day I could listen to my body with patience and care and time like I’d never had before. I felt my body change. I felt the texture and tone and purpose of my movements change. It was like starting over or going back to nature, unlearning and relearning all at once. My body and my dancing have become truly mine during this time, my deepest comfort and my sacred respite throughout this trauma. So I’m a little more sensitive now, and perhaps that’s why I recoil a bit from the idea of someone imposing the demands of unison on my liberated body. And I think perhaps I’m not alone in this.

I’m dreaming of a new unison. I’m dreaming of a new ethos of dancing together. One that advances the depth of individual identity and expression and values dancers’ agency. One that is cooperative rather than authoritative. One that feels informed by our collective trauma and guided by a responsive community and inclusive intentionality.

I’m asking: what if unison were an art of consensus and a practice of radical empathy?

I’m digging into the aesthetic implications as well. I’m curious how this “new unison” might manifest, both as process and product. How might it shift our creative practices and prevailing culture? How might it look different? How might our vastly different bodies, experiences, abilities, and identities be fully embraced in the pursuit of unison? Harmony comes to mind here–a unison that depends on, and is in fact enriched by, difference.

So, is this about a cultural shift, aesthetic shift, or both? In my mind, the two can’t really be separated. There’s an ethical component to it all, that what matters is not just what we do but how we do it. How can we tap into the way dancers have shaped ourselves as determined, resilient individuals over the course of the pandemic? How can we shape that into a new unison that reflects these experiences and channels our shifted kinesthetic awareness? A new unison grounded in a mutually empathic process—one in which choreographers and dancers might be challenged to listen more to each other—might very well be more enriching to create, more rewarding to dance, and more satisfying to watch.

I believe a new unison could be a generative force that brings us closer together as a community. We’re building back trust in ourselves and each other, and this is the time to think deeply about our creative processes. In moving toward a new unison, we might use the pandemic as a portal to a new world. I think I’d like to move in that world. I think we’d like to move in that world. All together now. (5 6 7 8)

Even (perhaps especially) now, nothing I do happens alone. Many thanks to my dear friends and colleagues Nick Brentley, James Gilmer, and Amy Seiwert for the long conversations and endless inspiration.

Photo of Sarah Cecilia Bukowski by Karina Furhman • Image description: Sarah Cecilia Bukowski is a mixed-heritage Latinx cisgender nondisabled woman with light brown skin and short dark hair. Sarah strikes a casual dance pose in profile with one arm extended behind and the other arm bent in front of her body. She stands on a pier with long railings on either side, framed against a light-colored daytime San Francisco cityscape. She wears a goldenrod tank top, black skinny jeans, and black high top sneakers.

Sarah Cecilia Bukowski is a Colombian-born, Lenapehoking-based dancer, writer, arts administrator, and community activist. She is a non-disabled, queer, cisgender woman of Costa Rican and Polish-Irish heritage.

Sarah discovered her love for dance at age three and hasn’t stopped dancing since. Her sixteen-year professional performing career stretches from New York to the San Francisco Bay Area and beyond, moving between ballet, contemporary ballet, modern dance, performance art, film, and multidisciplinary collaborations. Performing credits include Amy Seiwert’s Imagery, Hope Mohr Dance, Robert Moses’ Kin, Oregon Ballet Theatre, San Francisco Opera, Oakland Ballet, and Dance Theatre of Harlem Ensemble. Last fall, Sarah resumed her part-time undergraduate degree studies in dance and anthropology at Columbia University School of General Studies.

In addition to dance, writing follows Sarah as a parallel passion throughout her life, and she writes regularly about issues of cultural equity and social justice in dance. Sarah is passionate about engaging communities in conversation and crafting transformative change through arts activism by challenging traditional mindsets and learning collaboratively in grassroots settings. Her long-held passion for the written word motivates a deep inquisitiveness for the potential available at the intersections between social issues, creative processes, and the moving body. Her personal mission is to use these platforms to create a more just, equitable, and sustainable future for dance.

Find more of Sarah’s writing as an independent blogger, Writer in Residence with Amy Seiwert’s Imagery, and collaborating wordsmith in activism with Dance Artists’ National Collective.

Support: @sarah–cecilia

Website: sarahceciliadances.wordpress.com/blo

The thing is, people said you could catch it. In other words, it was contagious. And even though I had never seen or heard of any other kid my age catching it, there was a deep paranoia that I could be the very first one, making me a pioneer of sorts. Nearly every Sunday, this fear of the inevitable chased me into the basement of the church where I’d stay awhile, hiding in the stall, waiting for the thumping and shouting above my head to cease.

Because, surely, they would be jumping, and I knew they would be crying, flailing, falling. I knew how it made them loose and agile beyond explanation and inspired strength in the least expected. That someone was bound to jump right out of their shoes and take off sprinting around the sanctuary. I had seen how it made the bodies of elders ageless. How it made wailers out of the men. Shouters out of the otherwise reserved. Author of The Healing Rituals of Africa, Malidoma Patrice Some calls the dancing body a diagnostic tool, one that has the power to “bring out of hiding the parts of the body that are masked or that are being subjected to severe control by unnatural forces.” (Some, p.270) I’d take this a step further and say coming out of hiding was not only parts of the body, but an essential part of the soul.

The ushers, who would slowly make their way down the aisles, formed several small circles, each surrounding one dancing body and acting as a barrier to guide and protect. They would go on this way, until the jumping, shaking, stomping bodies collapsed into the pews or onto the floor beneath them. A white modesty sheet covered the legs of women, their tights, heels, and orthopedic shoes sprawling out from underneath. I never liked to see them this way–affected for the better or worse, I couldn’t quite tell.

Through the lens of three dance rituals and their wider religio-spiritual movements, we will explore three rites of revival that center the dancing body as a site of liberation. The Latin root revive translates to “live again.” From shout and the Ghost dance of 1870 to krump dance in the inner city of Watts, Los Angeles, the dancing body has been the site of reckoning and new life.

“Getting Free”

A colorful painting that depicts eight Black dancers and four Black musicians performing the ring shout dance in the Gullah Geechee region of South Carolina.

Catching the Holy Ghost—or the movement known as shout–has its roots in the ring shout, a dance ritual most notably practiced by the geechee of South Carolina and other Black folk on the coast of Georgia. It travelled here among the uncounted Africans shipped from the shores of Western Africa to the ports of Charleston. Southern slave masters fearing the potential of slave revolts strictly prohibited drumming and dancing on plantations, as well as in the early Baptist church, defining dance as any movement that required the feet to leave the ground. Characterized by its low-shuffling footwork, counterclockwise traveling circle, and an unchanging hand-based rhythm, the ring shout deemed itself a safe way to revive and reimagine the spiritual rituals of the past.

The ritual could, and often did, continue for hours on end, increasing in speed and intensity, raising the keepers of the ring to climactic levels of excitement and fervor. Durational in its nature, the shout whirls on and on, time in reverse, bodies flirting with exhaustion, driven beyond the point of physical fatigue into an apparent spiritual tirelessness. In this way, to echo the words of Josephine Baker, ring shout dancers liked to “die breathless, spent at the end of a dance.” And although Baker was referring to her actual death, I always loved this image–dancing oneself free from the body. And in the case of ring shout dancers, maybe even free from the limitations and identities prescribed to them as enslaved bodies.

Spent is what any good marathon runner knows well, or a mother in labor and birthing new life. Being spent is the experience of pushing beyond logical notions of what is possible and available to us in spite of our bodies. In this way the dancing body becomes the portal to this truth of more–more energy, more resources, more life. Not only do we see dance being centered as ritual practice throughout various Black and Indigenous religio-spiritual movements, but we also see a consistent presence of the spent body as a necessary ritual element.

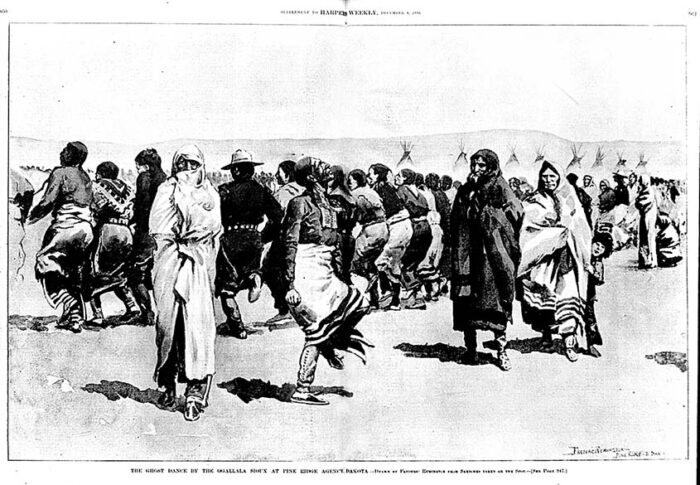

A black and white illustration featuring several members of the Oglala Lakota performing the Ghost Dance on land currently known as Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota.

The Ghost dance religion of 1890, like many religious practices of Native Americans, centers dance as ritual. In his book The Ghost-Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890, James Mooney characterizes it as a revitalization movement wherein the performance of the Ghost dance empowers the strength of the ancestors to help bring an end to American westward expansion and the erasure of native life. (Mooney, 24) Throughout the late 19th century, the movement rapidly spread among the Paiute, Sioux, Lakota and other native nations across the West coast; so much that it drew the attention of the federal government which was growing unnerved by the possibility of an uprising emerging from the cultural revitalization this dance promised. As the Ghost dance expanded through the late 1800s, the church revivals of newly converted Black Christians were also gaining momentum in the South. Mimicking the revival fervor that spanned much of the 19th century, the Ghost dancers also contained in them the belief that the body could serve as the site of divine intervention.

Though uniquely its own, the Ghost dance, sometimes referred to as the circle dance, shares many of the ritual aspects of ring shout. Specifically, the travelling of dancers in a counterclockwise circle who rely almost solely on the same low-shuffling footwork. Ghost dances were performed across the southern plains, and could attract hundreds of participants; it was not abnormal for the ritual to last many nights. Like in the ring shout, practitioners of the Ghost dance could be found collapsing at the end of their dance, spent and on another plane entirely. American ethnographer James Mooney, who was dispatched by US officials to investigate the rapidly spreading movement, extensively documented the emergence of this new religion and the impending threat of the ritual dance characterizing it. Interventions by the US government would eventually lead to the infamous massacre of over 200 Lakota Indians at Wounded Knee.

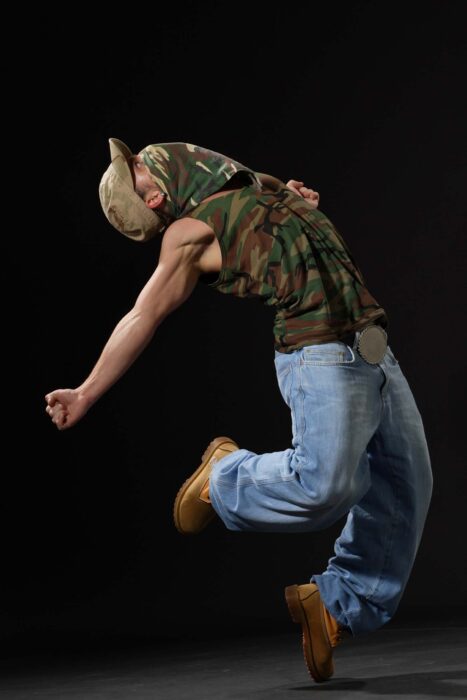

It would be that same threat of extinction calling for the dancing body in Watts, the inner city of Los Angeles. One hundred and ten years after the Ghost dance, we again encounter the spirit of shout readapted through a growing phenomenon called krump. Everything from shouting, twerking, popping, West African dance, to acrobatics and vogue can be recognized in the movement of krumpers. It is probably most notably recognized for its wild style of movement and satirical performances of battle, or what the ethnographer Max Gluckman referred to as “African rituals of conflict.” (Norbeck, 198) In a 2019 article on clowning and krump, Sarah S. Ohmer notes how “the ritual style war and art of battling makes up a central component of hip-hop’s culture and its evolution as a movement, in all of the four elements” including DJing, MCing, graffiti, and dance.

A colored photograph that features a male krump dancer balancing on one foot with his focus upwards and arms extended.

However, krump does depart from other expressions of hip-hop in that to be fully embodied in the dance practitioners must essentially abandon the body. Reminiscent of being spent, this point of ascension consistent with shout and the Ghost dance is referred to by krump dancers as “striking” or being “struck.” Akin to the practice of possession seen in most African based spiritualities, being struck is the experience of submitting to a force, or spirit if you will, much greater, stronger and dynamic than the self alone. Performers of the dance ritual, especially its original creators and most dedicated practitioners, express the belief that krump revives an ancestral memory of liberation and tribal cohesiveness that counters realities of the oppression and disunity experienced in daily life. Evident in the 2005 documentary RIZE by David LaChappelle, krump is more than a dance. It’s a spiritual practice available to anyone who desires to get free.

I’ve come to appreciate the spent, abandoned, and uncontrollable bodies that used to run me out of the sanctuary in fear. Only now, I revel in the intelligence therein. The legacies of shout, Ghost dance and krump reveal to us why the dancing body prevails as a site of liberation. Our ancestors, despite death-dealing oppression, perceived that there was, within their own bodies, an inexhaustible reservoir of “other” being. Denied both rest and resistance, they gave us revival.

Bibliography

LaChapelle, David. Dir. RIZE. Lions Gate Films, 2005.

Jung, CG, De Laszlo, Violet. The Basic Writings of C.G. Jung. Modern Library: Random House, 1959.

Mooney, James, The Ghost-Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,1965.

Norbeck, Edward. “9 African Rituals of Conflict.” Gods and Rituals edited by John Middleton. The Natural History Press, 1967.

Ohmer, Sarah. 2019. “In the Beginning there was Body Language: Clowning and Krump as Spiritual Healing and Resistance.” CUNY Lehman College Academic Works, 2019.

Some, Malidoma. The Healing Wisdom of Africa: Finding Life Purpose Through Nature, Ritual, and Community. Penguin Putnam Inc., 1999.

Photo of Nehemoyia Young by DeVonne Jackson • Image Description: Image of African American woman standing on a railroad track in upstate NY. She sports purple braids and white coveralls.

Nehemoyia Young is a Brooklyn based artist working at the intersection of art, spirituality and social impact. She is a graduate of Union Theological Seminary with a Masters in Theology, Performance Art & Ritual. Nehemoyia has worked with Okwui Okpokwasili, Renegade Performance Group, and David Thomson among many others. Her work has been featured at Movement Research, Judson Church, Danspace/St.Marks Church, Wild Project and Spelman College. She is one half of In Liberated Company, a dance based initiative addressing religious trauma among ex-fundamentalists. Recent appearances include the 2021 DanceNYC symposium panel “Dance to Abolition, Liberation, Decolonization and Reparations”, “WTF is Going on with Spirituality?” hosted by digital wellness platform, Ethel’s Club, and Union Theological Seminary’s “Social Entrepreneurship Series.” Nehemoyia is a 2021 Moving Toward Justice Fellow.

Support: CashApp $NehemoyiaYoung

Photo of Eva Yaa Asantewaa by Scott Shaw • Image description: Eva Yaa Asantewaa (she/her) faces the camera against a teal-colored background. She is a Black woman with medium-brown skin, dark-brown eyes, and very short grey hair. She’s wearing a multicolored, sleeveless dress with a scoop neckline and dangling earrings made of plastic feather-like pendants and pearls. Wearing cranberry-red lipstick, she’s smiling warmly, her head tilted slightly towards her left shoulder.

Eva Yaa Asantewaa (pronouns: she/her) is Gibney’s Senior Director of Curation as well as Editorial Director for Imagining: A Gibney Journal. She won the 2017 Bessie Award for Outstanding Service to the Field of Dance as a veteran writer, curator and community educator. Since 1976, she has contributed writing on dance to Dance Magazine, The Village Voice, SoHo Weekly News, Gay City News, The Dance Enthusiast, Time Out New York and other publications and interviewed dance artists and advocates as host of two podcasts, Body and Soul and Serious Moonlight. She blogs on the arts, with dance as a specialty, for InfiniteBody.

Ms. Yaa Asantewaa joined the curatorial team for Danspace Project’s Platform 2016: Lost and Found and created the skeleton architecture, or the future of our worlds, an evening of group improvisation featuring 21 Black women and gender-nonconforming performers. Her cast was awarded a 2017 Bessie for Outstanding Performer. In 2018, Queer|Art named one of its awards in her honor, and Detroit-based choreographer Jennifer Harge won the first Eva Yaa Asantewaa Grant for Queer Women(+) Dance Artists. In 2019, Yaa Asantewaa was a recipient of a BAX Arts & Artists in Progress Award. She is a member of the Dance/NYC Symposium Committee and the founder of Black Curators in Dance and Performance.

A native New Yorker of Black Caribbean heritage, Eva makes her home in the East Village with her wife, Deborah. Sadly, their best-cat-ever Crystal traveled over the Rainbow Bridge on February 18, 2021.

Photo of Monica Nyenkan by Jakob Tillman • Image Description: Monica Nyenkan is the daughter of African immigrants. She has dark brown eyes and hair. In this photo, her hair has two-strand twists.

Monica Nyenkan is a Black queer community organizer and arts administrator hailing from Charlotte, NC. She graduated from Marymount Manhattan College, with a Bachelors in Interdisciplinary Studies. Currently based in Brooklyn, NY, her artistic and administrative work focuses on creating equitable solutions with and for historically marginalized communities in order to make art more accessible. In her free time, Monica loves to watch horror films and share meals with her friends and family. A fan of educator and historian Robin Kelley, Monica firmly believes the decolonization of our imaginations will help facilitate a more radical and inclusive way of living.

DISCLAIMER: Opinions expressed in Imagining: A Gibney Journal are the writers’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views, strategies or opinions of Gibney.