Imagining

A Gibney Journal

Issue 9

Letter from the editor

Writing to you, dear March readers, from the second week of January 2022 is kind of like writing to you from the next day after a pretty snowstorm in downtown Manhattan. Know what I mean? Wrong season for this additional imagery but, let’s just say, the bloom is already off the New Year’s rose. And what’s with these 2020s, eh? Are we always going to have it this rough?

But today, I got word of two appointments in the dance field that are really upbeat! At the time of this writing, former Gibney colleague and much-missed Regine Pieters has been announced as Programs Manager for Center for Performance Research (CPR). And Urban Bush Women has named choreographer Paloma McGregor—a former UBW dancer and extraordinary community leader—as the new Associate Director of its annual Summer Leadership Institute. Congratulations to my friends, Regine and Paloma! Gotta say, these two Caribbean-born sisters have always lifted my heart, and we surely need more good news like this in the world of dance.

Today, I want to write about the power of conversation, particularly as we continue to make our way through crisis. In late December, a longtime friend left a voicemail message wishing me Happy Kwanzaa. I retrieved her message late at night and got back to her the next day. It was nice to talk about what we’re each doing to survive these times, but I was taken aback to hear that she—a Black woman with diabetes—was wary of getting vaccinated for COVID-19

The world had just heard about the Omicron variant and, with that thought fresh in my mind, I went to work. I pulled out two years of information that I didn’t even realize I fully comprehended. I launched into a mini-tutorial with pauses for laughter and her periodic cries of “I’m so glad I called you!” and mine of “I’m so glad you called me, too!”

Readers, when this fact-filled laugh-fest was finally over, I had bagged my quarry. She decided to get the vaccine!

When we hung up, I thought about the spontaneity of what had happened—perceiving a problem and quickly seeing an opening for a solution, trusting the moment and trusting myself, and calling upon the power of connection—two queer women of color. I realized she had probably never shared her confusion, doubts, and fears with anyone with whom she felt she had enough in common. And it’s very possible that’s the real reason she called. Happy Kwanzaa, indeed!

I’m writing about this now, because I know there are many conversations out there that need having about all sorts of things, and some have your name on them—just like this one had mine. Someone needs what you know. When the time is right, they will come to you, and I believe you will be ready.

I also want to suggest that Imagining can provide great conversation prompts. Our writers share so much that you can share with others and then sit down (or Zoom up) with them to take the discussion further. It’s exciting to know that what we offer here can have ongoing life out in the world.

Please don’t keep this to yourself. Enjoy, share, discuss!

Thanks for reading!

Eva Yaa Asantewaa

Editorial Director, Imagining: A Gibney Journal

Imagining Digital

Just weeks ago, my wife and I celebrated our fifteenth wedding anniversary, a milestone that seems both a “given” and a triumph. We met in college, both students at the same conservatory program and had the extreme fortune of both being hired by the same dance company in New York City at graduation–a gift that is basically unheard of for a couple. We have spent our life together inspiring one another to pursue our creative outlets and, at times, that has left us in different cities or hemispheres for years on end. We have supported one another from a distance with a grace and beauty that I would have never thought possible. Our relationship has been an evolution that has been based largely around the role that dance has played in both our lives and, as we began looking toward the next decade of our life, we tried to sew new seeds that would lead us to togetherness on a more permanent basis.

Our bodies were catching up to us, our souls missed one another, and the comforts we may not have needed at 20 began to seem more desirable and necessary in this chapter of our lives. Just before COVID took over the world and, more specifically, the arts, we had decided to open a dance company—TheDynamitExperience—as a way for us to both collaborate artistically and be located in the same zip code for more than a seven-day stretch.

We had anticipated the transition from performer to artistic director to be a gradual one. Something we would grow into over several years, similarly to how we planned to grow into living full-time with one another again. COVID however, had other plans for us.

First, I must say that we—while tired of COVID, as I am sure most people are—have also developed an immense respect from our experiences over the last two years to which we would have otherwise been blind. COVID brought many things, but its most fruitful gift was time.

Suddenly, we were gifted with amazing amounts of time, something we had not had together in over a decade. We began to cleanse ourselves, shedding dead weight and bad habits, facing some long overdue debt realities, and learning to add art back into our lives via technology. But, in spite of the reflective personal work we were doing, my newfound love of bicycling, and the growth that was clearly happening for us, we also found ourselves experiencing these very epic lows and feeling very, very alone even though we were less than fifteen feet from one another basically 24 hours a day.

The questions were insurmountable. How would we survive this financially? What would this mean for TheDynamitExperience? Why am I incapable of turning my socks right-side out before I put them in the dirty clothes? Should I become a long-haul trucker? Seriously, nothing was off the table.

Our company was conceived to not just be a performance-based body, but also an incubator for the community and artists alike to find unique and variant ways to connect and speak through movement. We had built our concept around linking people’s thoughts and feelings together while creating work that spoke to everyone about the realities we experience daily. We had envisioned the company acting as a catalyst to bring concepts that were difficult to handle—such as love, depression, anger, and fear—out in the open as a conversation through movement.

The pandemic made us hyper-focused on our inability to pursue any of those things, until we ultimately realized that we were personally in need of those very things.

We as a couple needed to be proof positive that you truly could bring the things you cannot say to the table through movement, lay them vulnerably out in front of someone else and let them contribute and build on them adding in their own insight, variation, and personality so that at the end you are both moving together, understanding one another and supporting each other as you progress. We needed to apply our mission statement to our marriage in order to find ourselves again, strengthen our ties, and create a future for TheDyanmitExperience.

Photo by BeccaVision

Image description: tan background, artistic directors

Latra Wilson (L) and Winston Dynamite Brown (R)

locked in a mid-stride partnered stance glancing

away from each other.

With this in mind, we began to really examine what made us whole as a union. Where were the cracks? Where was the history? What did our lineage add to our current condition? How could we honor those people in our lives who had unconditionally supported us? How could we honor one another and how could we express ourselves through movement in a time where stages were dark?

We both have always strived for authentic expression in our artistic endeavors and have worked hard for our works to stay relatable to our history and specifically the people who raised us. We started to lean heavily into what COVID seemed to take away from us and identify ways that we could eliminate the space we felt in our own home so that we could collectively work and connect in harmony.

We also began to acknowledge that our marriage has only been as successful as the community we have surrounded ourselves with over the years. We have benefited deeply from the counsel, encouragement, and strength of our family, friends, and dance communities. We knew very quickly that this time of our life could be no different. In order for our marriage and our company to grow we needed to solidify our new community both on and off the marley.

This proved to be an unbelievably rewarding experience. Due to the limited and unique circumstances COVID presented in building networks and communities virtually, it really required us to think outside the box. Through this collaboration with one another we began to cultivate these organic connections that lead to both virtual and community “play sessions,” free movement workshops, and conversations both verbally and through movement about “love” and “the foundations love can build.”

As a couple, we were able to work through this transition in our lives in a very public and very movement-based way: to establish goals that aligned both with our work and our home and to walk away knowing that both onstage and off we will remain intact as a union. We will create a world that relies on individual commitments that benefit the whole. We will honor the necessity of community in our own lives through work that showcases the people who raised us, look like us, and believed in us. We will continue to forever evolve both personally and professionally through constant creation, community engagement, and our shared pedagogy, and we will honor the things we cannot say by expressing them through movement.

COVID has allowed my wife and I to pause, to see one another again, to see the people in our lives as they truly are, and to build a company that is close to our hearts and our story.

TheDynamitExperience is our collective strength exposed through public expression. It is everything we are, everything we lack, everything we dream of. We hope its collaborative works will not only continue to bind us, but also bind the communities we work in while creating meaningful conversation–as this process has done for us personally–around topics that are sometimes hard to voice.

As we walk into 2022, we acknowledge that the hardships of life will never disappear. Instead, they will come in waves, as does joy. We now feel confident in our ability to weather those waves.

We have laid the foundation of change for ourselves and created a tangible reminder in our company’s mission statement to set our expectation of strength, not just from the works we create, but also the mark we leave on one another and our community. We will continue to create visceral experiences through contemporary choreography and community engagement, by examining the human condition and our relationships to one another. We will continue to grow and explore movement that resonates not just with our audience but within ourselves. This is only the beginning of a conversation that will long outlast the pandemic, just as our relationship will.

Photo of Winston Dynamite Brown by BeccaVision

Image Description: Tan Background with Winston

Dynamite Brown, a Black male with hair pulled up and

a dark beard, smiling softly at the camera wearing a dark

black tee shirt unbuttoned to show a glimpse of his chest tattoo.

Winston Dynamite Brown is currently a member of the Camille A. Brown & Dancers company, most recently performing in Fire Shut Up In My Bones at the Metropolitan Opera. Over his career, Dynamite has had the pleasure of working with Taylor 2, and most recently, Pilobolus, Sean Curran Company, Opera Theater St. Louis, Kyle Abraham/ A.I.M, and Company SBB Stefanie Batten Bland, to name a few. The DynamitExperience, a contemporary dance company founded in 2019 by Dynamite and partner, Latra Wilson, has been presented at The Mark O’Donnell Theater at The Actors Fund Theater, Manhattan Movement & Arts Center, Dance Adelphi, DanceWave, the SHED, Brooklyn Arts Exchange, among others. TDE serves as a platform for creative investigations and community engagement; the company creates work with an aim to impact the local community, specifically those that generally do not see themselves represented on stage.

www.thedynamitexperience.com

Instagram: @thedynamitexperience

Support

Venmo: @TheDynamitExperience

PayPal: Winston Brown, @TheDynamitExperience

Welcome.

I hope this finds you well.

My name is Jesse Obremski; my pronouns are he/him. I am a non-disabled, cis-gendered, Japanese-American artist, performer, choreographer, educator, director, and more. I have black eyes, short black hair, I am 6 feet tall, and I am usually wearing something from Uniqlo. I currently live in Harlem, New York, stolen Munsee Lenape and Wappinger land, where I primarily wrote this offering for Imagining: A Gibney Journal’s March 2022 issue. (I am recording this audio version of my written Imagining: A Gibney Journal offering in studio 4 at 890 Gibney.)

I often remind myself, and encourage others, to see the larger picture. Something that is easier said than done. It is a task that tends to be more difficult but vital because it requires community and conversation. It requires others and not just oneself. This offering in Imagining is part of my effort toward this ethos and culture. I share large questions often and by no means have any finite answers. However, I continually process and unpack them daily. In the ethos of a more global viewpoint, I want to take this time to remind us of the incredible work of first responders and health care workers especially through these trying years of Covid-19. Stay safe, and thank you.

I recently learned through research that the owl, in fact, does not have the largest field of vision. The bird with the largest field of vision is the American woodcock. I find this incredibly ironic because the United States has much to work on in terms of seeing all viewpoints of our world, in seeing all of humanity. In acknowledgment of how intention and impact may be different, this essay is in no way intended to isolate, prohibit, cover, and/or silo any experience but rather to highlight a viewpoint into cultural experiences and thoughts from an Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) perspective–a perspective that may support us in acknowledging the larger picture, the largest field of vision, and a larger spectrum of humanity. As we move forward in this essay together, I want to share a friendly reminder to accept breaks, take conscious breaths, and do what you need, away from the screen or device to take care today, tomorrow, and always.

Since joining Gibney Company, I have been diving into my Gibney Company Moving Toward Justice Fellowship. These fellowships are where each Artistic Associate explores and creates programming on a need we recognize within the field. OUR PATHS, my fellowship, which launched in the Spring of 2020, is where we cultivate, curate, and celebrate a culture of accountability, reason, and clear purpose towards greater communal empathy. In a culture of “who, what, where, when, and sometimes why,” I encourage us to challenge this norm and begin with WHY.

After reading Simon Sinek’s book Start With Why at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, I found OUR PATHS to be a springboard towards this culture of celebrating “why.” More can be learned about OUR PATHS at www.ourpaths.life. I invite us to continue forward with this written offering of personal viewpoints on how AAPI culture is viewed with a lens of curiosity, WHY, and empathy.

As a mixed artist, I continually have a complex time being able to settle in with this ever-developing “label” of myself. I am frequently asked by society and culture: “How do you identify?” or “Where are you from?” These questions suggest space for one to define what their identity is, but they force one to clarify and label oneself for that day, time period, or moment.

Photo of Jesse Obremski by ©Nir Arieli

Image description: Obremski is in a wide, rotated, bent joints, fourth with the left leg forward in front of a background that fades from black (on the left side of the frame) to red (on the right). Obremski is wearing light skin tone biker shorts with his left arm bent with his left first toward his heart. Obremski’s eyes are closed. To the left of the frame there is a faded image of Obremski from standing to the real Obremski in the fourth. The faded color is the red and we see the process with wavy red lines between the standing red Obremski to the realized Obremski in the fourth.

I recently had a conversation with a colleague, and we discussed how our culture often introduces one another by name and credentials. At an audition or job application, it is often the name and credentials. It is the who, what, where, and when, rather than the why. This relates to the culture of labeling. Everything is about seeing, perspective, context, balance, and I do recognize that labeling can also be a sign of immense pride.

I personally have immense pride as a New Yorker. My experiences in New York City are what have developed my passions, my drive, and the reasons why I do what I do. Though I am thankful to have been encouraged and supported by my family in sharing my identity as I grew up in New York, in retrospect, I became extremely naive about my personal ethnicity. I grew up without this other sense of pride: my heritage. With years of independent discovery on this and cultural progression, I ask, Why are things different for me now? This is our first “why” question and I invite you to keep note of them throughout this essay. Here is question number two: Why was I naive about my inner strength and not acknowledging my heritage?

Now, in 2022, we find ourselves immersed in a constant challenge to change the global culture, to shift and evolve. It is because our culture has to change. This is innately human as noted by Measure of America (www.measureofamerica.org) that human development is “the process of enlarging people’s freedoms and opportunities and improving their well-being.” Even though they define “human development” as such, is it really true? Whose “well-being” are they referencing?

Gilbert T Small II, currently Gibney Company Director, has had an extensive performance background with Ballet BC and an international perspective. Gilbert shared with the company, at the beginning of the 2021-2022 season in September 2021, that our “culture is shifting and it is going to get worse before it gets better.” This is part of the cultural revealing we are immersed in, and I believe there are multiple examples of this unfolding within our society.

In the midst of a global pandemic, assault on Black and Brown lives and marginalized communities yet again surged. George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Walter Scott. Rest in power. These are only a few of the individuals who have had their lives stripped from them. I specifically say marginalized communities because, in relation to the hate crimes on Black and Brown communities, there have been countless more tragedies and assaults on individuals across the spectrum of humanity.

Almost a year ago, on March 16, 2021, a shooting spree occurred across Atlanta, Georgia–in particular, at Young’s Asian Massage and Gold Spa. Eight people were murdered, six of whom were AAPI women (Delaina Ashley Yaun, Paul Andre Michels, Xiaojie Tan, Daoyou Feng, Hyun Jung Grant, Suncha Kim, Soon Chung Park, Yong Ae Yue). This sparked more engagement across our world with #stopAAPIhate.

All of these vicious acts point to the worsening condition of our society. Gilbert believes—and, in my heart, I share this belief—that we can get better. Communities are gathering together, affirming cultural unity and solidarity. Within the AAPI community, I have found a deepened sense of cultural purpose through festivals, activism, and conversations to highlight the full AAPI diaspora. Though there is this incredible momentum, here is “why” question number three: Why has representation barely been apparent within our dance culture? This question often comes up, though only the surface gets addressed. Does it really take the loss of lives to make movements for justice happen?

Hong Kong-born dancer, arts advocate, and activist Phil Chan, based in New York, is diving deeper. With Georgina Pazcogin—an incredible AAPI artist and soloist with New York City Ballet—Chan founded Final Bow for Yellowface in 2017. Final Bow addresses the usage of “yellowface” and Asian stereotypes within primarily ballet works and companies. Recently, Final Bow has expanded its support of AAPI artists.

“Looking around at other communities who have organized centers like Dance Theatre of Harlem and Ballet Hispanico, the Asian ballet community doesn’t really have that,” Chan told me. “We haven’t consciously made that space. Maybe it’s because we have been conditioned to be more passive, or perhaps because at least we are in the room if not fully at the table. So maybe it’s better just to keep your head down and work harder.”

“Conditioned to be more passive.” That’s oppression. Within oppressive US culture, based on colonialism and white supremacy, AAPI culture goes unseen and AAPI voices go unheard. It is unpromising that cries from AAPI individuals continually go unrecognized. This is a reality for many.

Though I recognize that I have this space to share through Imagining, I have been humbled with opportunities and have incredible support, this is still a reality for me as well. I have felt the cultural pressure to silence my voice while others speak over me. I have felt seen through the lens of stereotyping: that AAPI people work hard and do not speak. I have felt spaces of underappreciation and discrimination. This is real and is heavy, but I have been “conditioned to be more passive” to keep my “head down and work harder.” I have been affected by oppression.

A 2019 article by Zara Abrams for the American Psychological Association shared evidence from Ascend, Pan-Asian Leaders that AAPI individuals–representing 6% of the United States, the fastest-growing population within the US–“are frequently denied leadership opportunities and are overlooked in research, clinical outreach and advocacy efforts.”

“AAPI’s presence has been historically and conveniently washed out in this homogenized society, and often only Black and white conversations come up when we talk about race” shares Jie-Hung Connie Shiau, a Gibney Company Artistic Associate and choreographer. Jie-Hung–from Tainan, Taiwan–has a lived experience of a Third-Eye view of the United States. The washing out of AAPI culture limits the potential for a global community. It isolates AAPI individuals and has contributed to the rise of anti-AAPI violence in the United States.

Gibney Company is in our second creative process with Inaugural Choreographic Associate Rena Butler, exploring Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” from his book, The Republic. The theory is in The Republic, volume VII, with translation by Thomas Sheehan.

It opens with a sentence from Plato’s teacher, Socrates: “Next, said I, compare our nature in respect of education and its lack to such an experience as this.”

So, let’s explore this. This reference to education is a reason WHY I, and potentially many other AAPI individuals, grew up being naive. Artist or not. I was conditioned by society to have my inner voice be more passive through my education or lack thereof. To not recognize, be proud, or be courageous about my Japanese-American heritage. I was oppressed into invisibility.

American pop culture explodes with superheroes, and invisibility is often seen as an incredible power. But not this invisibility. This is disempowerment. I believe an amazing superpower, and therefore responsibility, is actually seeing, like the American woodcock, a wide field of vision. Seeing those who are invisible and even those made invisible.

It was my conscious intent to offer this essay for Imagining‘s March issue, two months before AAPI Heritage Month. I want to encourage us to examine if AAPI artists and others are recognized and supported in our society and its institutions only during May. Will there be increased visibility?

And that brings us to our next, and fourth, “why” question? Why give cultures and cultural movements just a single month of recognition? A necessary start, but this is silo-ing.

As Jie-Hung/Connie has said, “AAPI presence is often still under-represented considering how massive and diverse Asia is.”

There is so much to celebrate within the AAPI diaspora. In our effort to see a larger picture, let’s recognize that this is the same for Africa. The continent of Africa is incredibly diverse—historically, politically, culturally, artistically—and its great diversity is under-recognized in the white Western mind.

There are twelve months to a year. I invite us to find ways to celebrate every culture year-round because marginalized cultures are not invisible for the other eleven months.

Each time I have worked on this essay, I have asked myself, “What is different? What has changed from just one month ago?”

For one thing, I noticed more AAPI content on media platforms such as Netflix. At first, I found this exciting, but then I took a closer look through a larger lens. Maybe it wasn’t so much that more AAPI material was being presented. Maybe it was just the algorithm feeding back more of the kind of content I had supported in the past. It’s hard to tell what’s real.

One thing I know to be true from the people in my life is that AAPI individuals are hurting. This is real, and I see it. This brings us to our fifth question: Why does our culture need these constant reminders?

Though things may be tough, I feel optimism in my bones. There are those reminding our world of AAPI presence and doing the work. For example, Jessica Chen–an artist, advocate, and Founder/Director of JChen Project–has created festivals and movements to reveal more of the AAPI experience. Her festival, We Belong Here: AAPI Dance Festival, has the organizational support of Arts on Site, which has committed to producing the festival for the next three years. This is one example of sustained support of AAPI culture, experiences, and voices.

Where do you see sustained support of AAPI individuals in your life? How can we shine a light on AAPI artists who have felt invisible for so many years?

I encourage you to take a deep breath and be empathetic to yourself. I have posed large questions that take time to process. I hope you can find ways to bring yourself to my personal discovery and offering. I encourage you to take the “why” questions throughout this article and investigate for yourself, how do I approach these questions? How do I connect with them?

- Why are things different for me now?

- Why was I naive about my inner strength and not acknowledging my heritage?

- Why has representation barely been apparent within our dance culture?

- Why give cultures and cultural movements just a single month of recognition?

- Why does our culture need these constant reminders?

Thank you for your time in joining me to dive into these questions. I invite you to find ways to celebrate marginalized communities throughout every month of every year and uplift these voices.

I want to name and support the community of individuals who have supported this offering: Eva Yaa Asantewaa and Monica Nyenkan, the editorial team for Imagining: A Gibney Journal; Richard Sayama; Gilbert T Small II; Jessica Chen; Phil Chan; Jie-Hung Connie Shiau; Michael Greenberg; Rena Butler; Gibney’s Community Action Department, and all of you who have taken the time to absorb these perspectives.

I also look forward to hearing your thoughts as we continue our global conversation and development. Connect with me at jesse.obremski@gmail.com and www.jesseobremski.com.

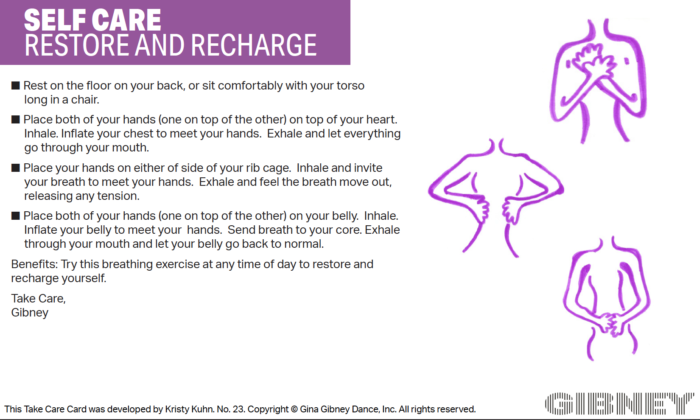

And, finally, I’d like to offer this Take Care Card, created by Gibney’s Community Action team, developed by Kristy Kuhn, as a way to support yourself moving forward:

Self Care:

Restore and Recharge

- Rest on the floor on your back, or sit comfortably with your torso long in a chair.

- Place both of your hands (one on top of the other) on top of your heart. Inhale. Inflate your chest to meet your hands. Exhale and let everything go through your mouth.

- Place your hands on either side of your rib cage. Inhale and invite your breath to meet your hands. Exhale and feel the breath move out, releasing any tension.

- Place both of your hands (one on top of the other) on your belly. Inhale. Inflate your belly to meet your hands. Send breath to your core. Exhale through your mouth and let your belly go back to normal.

Benefits: Try this breathing exercise at any time of day to restore and recharge yourself.

Take Care,

Gibney

A horizontal image with a white background and a

black thin-lined box contains the Restore and Recharge

invitations to the left. Inside this black box are three

drawings of torsos to the right. One illustration features

hands on top of the heart, the other shows hands on either

side of the rib cage, and the last portrays hands on the belly.

The Take Care Card title is on the top left in a purple box.

On the bottom right is the Gibney logo.

In mid-February, while this essay and Imagining Journal were in the editing process, Christina Yuna Lee was murdered in her Chinatown apartment. She was stabbed more than 40 times. This occurred within a month of numerous anti-AAPI hate crimes, primarily victimizing female-identifying individuals, especially in New York City subways and public spaces (Michelle Go, Atsuko Obando, Potri Ranka Manis, to name just a few).

According to NBC News, anti-AAPI hate crimes have increased by 361% since 2020.Jo-Ann Yoo, Executive Director of the Asian-American Federation, shares that this data is highly underreported. These hate crimes must stop.

I share my condolences, respect, and support to all who are hurting now and I invite everyone to take conscious breaths, be aware, and take care.

– Jesse Obremski

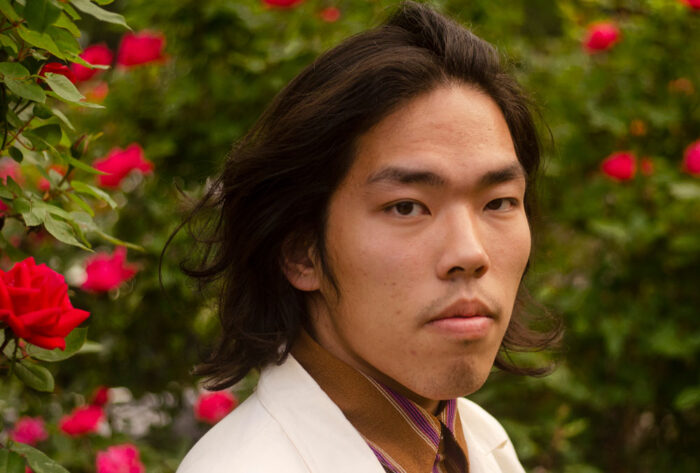

Photo of Jesse Obremski by Christopher Jones.

Image Description: Obremski with black hair and

black eyes is smiling towards the camera in front of

a rock-garden green gradient backdrop. Obremski is

bare-chested and the frame cuts off at his collar bones.

Obremski is tilted to the left of the frame.

Jesse Obremski (he/him), a native New Yorker, Japanese-American, graduated from LaGuardia High School and The Juilliard School with additional development at The School at Jacob’s Pillow with multiple years at The Ailey School, Earl Mosley’s Institute of the Arts, and Springboard Danse Montréal. Obremski, an Eagle Scout Rank recipient, Asian American Arts Alliance Jadin Wong Dance Awardee (2016), Interview En Lair’s “Dancer to Watch” (2017), and Dance Magazine’s (March 2019) Dancer “On The Rise” has performed with Earl Mosley’s Diversity of Dance, Brian Brooks Moving Company, Peter Stathas Dance, Kate Weare Company, Gallim Dance, and more, as a company member with Lar Lubovitch Dance Company, Buglisi Dance Theatre, WHITE WAVE, The Limón Dance Company (soloist and principal), and Artistic Associate with Gibney Company.

www.jesseobremski.com

Instagram: @jesse_obremskiFacebook: www.facebook.com/jobremski5

Support

Venmo: @Jesse-Obremski

Join us April 5-9 for the world premiere of Gibney Presents TERRITORY: The Island Remembers created by zavé martohardjono, x, Ube Halaya, Raha Behnam, Marielys Burgos Meléndez, Julia Santoli, Katherine De La Cruz, Jordan Reed, Theresee Tull, Proteo Media + Performance, supported by Maya Simone Z. and Rosza Daniel Lang/Levistsky.

Five deities invite you to a parable island. It is home to many beings, plants, histories, and memories—not all good. On the island live two communities separated by a colonial border. They grapple with division and reconciliation. What conditions can untangle human and climate disaster? TERRITORY uses multimedia, storytelling, rituals, and collective actions to envision a reparative future.

Photo by Kathleen Kelley, collage edited by zavé martohardjono.

Image description: Five deities in colorful costumes, masks,

and drag look into the camera lens and pose boldly. Behind

them is a digital backdrop of a lush green tropical environment.

APRIL 5-9, 12:00 PM-3:00 PM

GALLERY INSTALLATION

FREE

APRIL 7-9, 8:00 PM

GIBNEY 280 at THE THEATER (STUDIO H)

$15 – $20

APRIL 8, 8:00 PM

LIVESTREAM

$15 – $20

To purchase tickets for this upcoming premiere, visit gibneydance.org/calendar.

TERRITORY: The Island Remembers is curated by Eva Yaa Asantewaa for Gibney’s Spring 2022 Rising Up! season.

Photo by Whitney Browne

Image description: A wide shot of 2 deities

sitting around a table. In the foreground,

one deity in mid-sentence, gesturing with their

left hand. In the background, another deity looks

to be listening with a fan in hand.

Recently in her lecture for Camille A. Brown’s Social Dance for Social Change series, entitled Stories: Pointe, Pumps, Flats, and Tap, Theara J. Ward mentioned being penalized from promotion in a Black ballet dance company due to natural weight gain, hormonal changes, and a significant growth spurt from adolescence to adulthood.

This natural and biological transformation was a beautiful gift that spoke—and still speaks—to her unique design as a dancer. The bodily evolution that enlightened her quality of movement, enhancing exceptional abilities, became a threat in the context and culture of social dance–a place, at one point, where she could be herself, inside and out.

This was no longer what we now call a safe space but, as Theara shared, back then there was no such thing as a safe space. You just had to do and continue fighting forward, which is something that many Black women have always done.

For Black women, forging ahead in the midst of these fights can build strength, but also erode the innermost parts of a person.

This idea reminds me of the words R’n’B musician Eryn Allen Kane shared about women of color and generational trauma. In a 2019 Instagram caption beneath her music video “Fragile,” Eryn wrote, “We’re told ‘you’re tough as nails’ while we struggle trying to take on the weight of the world. We’re told ‘you’re not in pain’ when we are hurting. We manage everyone’s feelings, hiding our own tears, hiding who we are; it becomes second nature. We disassociate ourselves from our own bodies and feelings, as a means to cope, this can be a dangerous place to live in.”

Much of what many have experienced, inside and outside of the artistic realm, has affected the body tremendously, triggering a mental replay of intergenerational trauma. Trauma therapist Kobe Campbell (The Healing Circle podcast) shared a definition of trauma: an incident or a series of incidents that have lasting negative effects on our physical, emotional, spiritual, mental, financial, relational or social well-being.

We may often think triggers come from external entities, but clinical psychologist Dr. Shefali recently shared a video discussing the process of triggers, what happens when we get stuck in a dysfunctional loop of triggers, and how they ultimately come from within. Looking inward is the only way to change the impaired outcome.

Are you holding traumas hidden within your body that can become triggered in your everyday life? Eventually things do manifest. Sometimes we are carrying the unhealed trauma inherited from generation to generation. We encounter situations in life that are beyond our control. We also make choices and decisions that keep us bound, incubated in a form of enslavement. We end up fighting and rejecting ourselves, creating a war within.

Our bodies were divinely designed to heal. Unaware of this truth, we walk in the footsteps and legacy of fragility.

Photo by Katia Robinson

Image description: light skinned black woman at the beach. Tan colored sand beneath her feat with a bright blue sky and greyish-white clouds. She has on a white t-shirt with a black logo and barefoot with army fatigue pants on. Her arms opened wide with joy and she smiles. Her head and body are arched back with her left foot slightly beveled.

Speaking of her song, “fragile,” Kane said it expresses “the idea that my traumas are my mother’s and her mother’s. They’re passed down from one strong woman to the next.”

Repeated cycles, endless chains, and dysfunctional loops (Shefali, 2021) keep us externally masquerading freedom on the outside while we remain internally imprisoned. We wear the mask of loving and caring for ourselves–being presentable, pleasing, acceptable, and loveable, to the world around us–while continuing to neglect ourselves.

In her article entitled “Seven Diseases That Affect Your Health and What You Can Do,” Dr. Janine Austin Clayton, speaks directly to Black women about health considerations and risks, stating: “It is important for a woman to be the best advocate that she can be for her health. Women are so often the caretakers of their family, putting the health of others before their own. But wives, mothers, and daughters need to make sure that their health needs are met in order to be there for others.”

On an airplane, the flight attendants instruct passengers–especially parents with children–to put their emergency masks on first before helping anyone else. It might sound harsh, but if you run out of oxygen, you’ll die and be of no help to anyone else.

Some Black women artists have worked in environments that require them to be extraordinary and multifaceted in ways that have harmed them physically and spiritually. Despite their abilities, they may often face disdain for their attributes, features, and characteristics. While these challenges can strengthen the internal and external musculature–mind, body, and spirit–this can lead us to building our walls very high, blocking out bad input, with no vacancy for receiving what is good.

The spiritual essence and natural design of the artistic realm can curate spaces for Black women to understand their power, beauty, and worth. Creative collaboration and partnership allow them to be open, supported, vulnerable, and authentically themselves. This can be cultivated by doing the necessary work to plant, re-establish or re-pot circles and cycles of legacy within and among each other.

Cycles and circles can create chains or be divided disruptively to ignite sparks of healing.

In a 2016 YouTube video, author Toni Blackman breaks down the meaning of a cypher: “A cypher represents 360 degrees. It is about completion of thought, giving and exchanging energy, thoughts, information, and ideas. The cypher is a collective experience. Legends of hip hop said that we have been ciphering for centuries. We eat in circles, we pray in circles, and so much more. It represents our humanity.”

During her lecture, “Lessons from the Cipher: A Blueprint for Radical Inclusion,” in Camille A. Brown’s Social Dance for Social Change series, Shireen Dickson discussed how circles are eternal and never ending. They can be inclusive, exclusive, universal, and approachable.

The circle or cypher, especially in dance, is holistic, multifaceted, and multidimensional. The layering of rhythm, spirit, and physical communication, composes a circular arrangement that prophetically shifts the atmosphere to birth new life. This is a community. This is the healing that Black women create when they authentically come together. Community is about exchange, storytelling, love, memories, sharing, caring, joy, resistance, discomfort, frustration, confrontation, and so much more. Authentic community is the ascension to higher ground. It displays the evidence of life through the body and the inherent narrative of innovation that Black women have the ability to pass on. A restorative nature that can alter life through the circle, cypher, and artistic realm. Realigning and changing the trajectory of one’s existence.

We are living manifestations of our history, choices, and more. We are reflections of our community, but we also have the ability to create in spirit the change we want to be evident in nature.

Photo of Francine Ott by Janae Brown

Image Description: A light-skinned Black woman

with sandy colored hair with blondish highlights, purple

lipstick and gold hoop earrings. She has on a black top,

tattoos around her right wrist, and her arms are folded

leaning on to a black bar with her chin rested on her

hands looking out.

Francine E. Ott, a native of New Orleans, received her B.F.A in Dance from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette and has had the pleasure of studying with many artists that she admires. She has worked and danced with Camille A. Brown and Dancers, Ronald K. Brown/Evidence, A Dance Company, among others. She has had the privilege of teaching many workshops, classes, and residencies—as well as being able to showcase her choreography. Francine has received her Masters degree in Mental Health Counseling at Nyack College and is currently a Dance Lecturer and Director of Panoramic Dance Project at North Carolina State University. Ms. Ott has her own company, Francine E. Ott/The Walk, where she integrates mental health with dance and other art forms, allowing one to further their creativity through a unique therapeutic process providing a space for growth, healing, change, and transformation in one’s life.

Support

Cashapp: $Freewalk

Venmo: ottwalk@aol.com

Paypal: paypal.me/francineott

Zelle: ott.the.walk@gmail.com

Arising

It is towards the end of the performance, and I’m exhausted. My skin-tight costume is soaked with sweat, the stage lights seem extra hot and bright, and I know I have to save some energy to stick my final triple pirouette. I was told too many times during my lifetime of dance training that I was small for a male dancer, so I would have to dance big. And, boy, did I take those words to heart!

I know I can expand my energy to fill an entire auditorium. I know I can move my frame through space with the urgency and ease of someone twice my size.

I reach my mark in the space and settle into a wide fourth position, arms at the ready. I can feel the deep, delicious plié of my knees, and the power welling up and waiting from my quadriceps, calves, and feet. Sometimes, in the moment right before you start to turn, it feels like the world stops and the uncertainty of what is about to happen flashes in front of you. But you tune it out and trust your training to get you through.

As I sit listening to the assisted living facility’s head nurse interview my 65-year-old mother to see if she is an ideal candidate for their residence, a thought bubbles up from the depths of my awareness. How is it possible to hold so much relief and so much grief in one little human body at the same time?

As a highly-trained yoga and meditation teacher, I’m used to paying attention to my thoughts. That’s a main part of the practice. So, I’m fairly sure I’ve never had this thought before. It reminds me of one of my favorite teachings from Pema Chödron, the American Buddhist nun. In life, things never get solved. It’s all a continuous dance of coming together and falling apart.

Impermanence. In the yoga tradition, it’s like a big vinyasa, sometimes defined as the process of things arising, abiding, and then dissolving away.

As my mom, when questioned, fails to remember her birthday or what month it is, I feel deep sadness arise. I try to watch it with curiosity and compassion, giving it permission to pass through my body.

Abiding

With a deep breath, I push off my back leg, zip my foot into a tight passé, and feel my weight settle over my standing leg.

Lift off! My eyes stretch out over the audience looking for a spot to focus on, landing on the light from the tech booth at the back of the theater. As I finish my turn’s first revolution and begin the second, time seems to slow.

What I most love about dance is that it’s alive, created in the moment, and then it’s gone. Even if it’s repeated the next night, it’s never the same, and I won’t be the same, even just a day later.

I finish the second turn and begin the third. I feel a flash of doubt. I might lose my balance, might fall over, might make a fool of myself. Balancing practices expose something that humans often have a hard time sharing with each other–our vulnerabilities. Here I am in front of hundreds of people, taking that chance.

I can’t help but wonder what daily life in an assisted living facility might be like. Do people feel lonely? Is it a test of human resilience and adaptability? Do people make genuine connections here? Are they even aware of where they are?

We get so adjusted to our daily lives and routines that we can move around as if in a daydream, and then something occurs that shakes us wide awake: a partner decides to leave us, a friend receives news of a terminal illness, we are fired from our job without a good reason.

We all like to cling to what’s familiar—in Buddhism, we call that attachment—and not reconcile with the fact that nothing lasts forever. We have to get comfortable with the notion that the other shoe will eventually drop.

I’ve heard that with dementia, the person having the experience is usually the happiest person in the room. It’s everyone around them who is struggling. The person with the disease must find that it’s slowly getting harder to wake up to much of anything, and they just abide in the present moment, most of their mundane worries long forgotten. Time must begin to feel blurry when you’re no longer oriented towards goals but, instead, moment-to-moment experiences.

I look over at my mom and see that she’s nervous. She keeps glancing at me, fidgeting, and then apologizing for not knowing the answers to the nurse’s questions. I offer some words of encouragement, and the interview wraps up just a few short minutes later.

Dissolving

The final revolution of my triple finishes, and I land gently with my arms outstretched. Even though my body has stopped moving, I can feel the effects of the spin rippling and reverberating through my awareness, and my weight begins to settle. It’s over.

Learning how to execute a triple pirouette took over twenty years of daily training and, for tonight, all those years did their job. I took a chance, lived in the moment of the experience, and now I’m already watching it fade away.

Dancing is like a big vinyasa. Each movement comes to life, hangs out in space for a few moments, and then vanishes back into space allowing for the next movement to arise. This pattern continues, over and over, until the piece is completed.

I run off stage and listen to the final few swirls of music as the performance finishes and the lights go dark. I already start to feel my mind stretch towards tomorrow when this entire cycle begins again, but I remind myself there are bows to take, friends to greet in the lobby, and a night of deep rest ahead.

At the assisted living facility, I rise and give my mom a huge hug. She asks if we can go get coffee which I think is an excellent idea. As we load into the car she says, Those were such nice people, who were they again?

I feel my heart do a bittersweet backflip. I can see the memory of what just happened is already dissolving away for her, but at least I know she’s not worrying anymore.

They would be really nice folks who would help you live here, Mom, to make lots of friends, cook, clean, and thrive! I think you would love it.

Do my words sound genuine? I wonder about that even though I know they are the right words. I’ve attended many silent meditation retreats, and I know humans love to fill space with chatter. Sometimes when you don’t know what to say, saying nothing might be the best option.

We sit in the car in silence for a few minutes, the radio mumbling in the background. My mom turns to me and says, Remember when I was a dancer? In Germany? I was pretty good!

I’ve heard the story many times. She wanted to be a professional dancer and went to one New York audition where they told her she was too small. She gave up the dream on the spot.

She stretches her arms into a big circle in front of her as if she’s turning. I make the same motion, and suddenly we’re both laughing again.

We pick up the coffee and head back towards my brother’s house. The interview at the facility is already history. What comes next, I don’t know. But right now I’m happy—abiding in this very tender, fleeting moment, dancing this big vinyasa with my mother.

Photo of Hunt Parr by Jimmy Fisher

Image description: Hunt Parr is wearing a dark

blue shirt with a gray horizontal stripe on the shoulders.

His dark brown hair is cropped close to his head. He is

staying outside and his focus is pulled to the left.

Hunt Parr is a yoga/meditation teacher and professional dance artist based in New York City. Originally from Alaska, he completed his BFA with honors from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, going on to dance with many companies and choreographers worldwide. He is also an experienced registered yoga teacher with the Yoga Alliance, having over 1000 hours of yoga teacher training from some of the most respected teachers today including Cyndi Lee who he assists. His expertise has been called upon commercially as a yoga teacher for A&E Networks, Animal Planet, and the History Channel. His work has been featured on the Huffington Post, Yoga International, and he currently serves as a private yoga teacher for many well-known NYC public figures and celebrities. He also teaches on the award-winning faculty at MindfulNYU. Hunt is a serious student of Tibetan Buddhism, a certified life coach, and a Reiki master. He hopes to hear from you.

huntparryoga.com

Instagram: @huntparr

Facebook: www.facebook.com/HuntParrYoga

Support

Venmo: @hparr

Paypal/Zelle: hunt.parr@gmail.com

At 16, parted from my mother and my motherland, I danced for the first time in my life. I don’t mean the historically reductive kind of dancing that insists on the physical exploration of movement in time and space. Rather, I hold onto the early memories of letting loose in the clubs, surrendering to the night, becoming one with the sweaty bodies, the pounding sonic vibration, the warmth of social friction, and the collision of overlapping temporalities.

Dance was ecstatic.

Dance was undoing.

Dance was survival.

Dance was a feeling, a transient interpersonal and political sensation with everlasting clarity—an affective shuttling between delirious overwhelm, orgasmic dissolution, selfless devotion, and fearless unraveling.

In a typical Dionysian manner, dance found me at the same time as I found alcohol. My high school friends in the UK and I were drinking so often and so heavily that we thought blacking out was just something that happened every time you consumed alcohol. We were a bunch of teenagers from all different countries recruited in this utopian experimental school system born out of the Cold War era, called the United World Colleges (UWC), whose mission is to use education as “a force to unite people, nations and cultures for peace and a sustainable future.” Put in more plainly, we were the brainchild of well-meaning philanthropy, the lab rats for neoliberal ideological articulation, the seeds of the next generation’s world leaders in the age of accelerating globalization.

I was oblivious to UWC’s insidious and invisibilized whiteness, to its contradiction of encouraging yet flattening differences. Naïve and idealistic, I was intoxicated by the notion that I was devoting my study to something larger than myself: world peace and sustainability. This commitment to a common purpose, a greater good is a historical feeling I inherited—a lot of us Vietnamese take immeasurable pride in the persistence and sacrifice it took to wage decades-long total resistance wars against two of the most powerful empires in the 20th century, France and the US.

I latched onto this sense of familiarity, this fragment of Vietnamese-ness that can be somewhat translated and integrated into this new neoliberal bubble. Which would also mean, whatever parts of me, my upbringing, and my culture that were implicitly deemed uncivilized and unproductive had to be renounced in this forced assimilation process. Needless to say, there was a lot of pain, anger, and sadness being produced individually and collectively, especially for us “third world” kids having to lose our mothers, our mother tongues, and our motherlands to survive here. Perhaps, we all thought it was the necessary sacrifice to make if we wanted to do something greater with our lives.

Our alcohol consumption, then, could easily be pathologized as escapism. There was a lot to escape from, as we kids were absolutely not equipped to deal with the flood of grief unleashed by this educational experiment. In this sense, my utopian devotion to the night, to dancing and its delirious sociality was, at all times, coupled with the frenetic movement of running away from the emotionally unbearable reality. I was having the best time of my life and going through an immensely transformative period. But this facade of euphoria was sustained by blissful ignorance, oblivion, and forgetting.

In the ambivalence of ecstasy and pain, pleasure and sadness all coexisting in the act of dancing, I wonder about a meaningful counterbalance to the pathological interpretation of dance as a refusal to confront reality. Can dance’s selfless devotion to the night, its delirious transportation to an otherworldly realm, and its orientation away from reality at the same time enact a tumultuous return to a historical sensibility that is no longer accessible in the here and now?

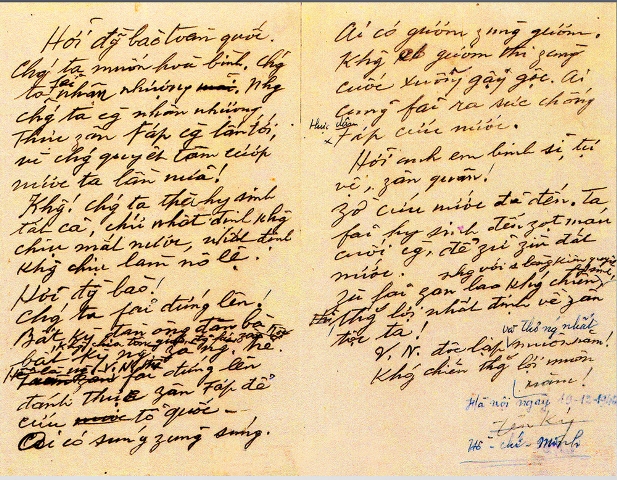

“We would rather sacrifice everything than lose our country and become slaves,” declares Ho Chi Minh (December 19, 1946) as North Vietnam launches a total resistance war against France’s attempt to regain its colonial control of Indochina after World War II.

These famous words by Uncle Ho are written in the wake of utter devastation caused by fascist Japanese occupation of Vietnam, further foreshadowing an insurmountable amount of death necessitated by the next three decades of wars. This call to sacrifice returns to me in these difficult times, where ceaseless death is simply considered as a byproduct of productive life. In this era of “make live and let die,” to borrow Michel Foucault’s canonical formulation of biopolitics, I am longing for meaningful life and purposeful death.

Image Description: Pictured is the original copy of Wage Resistance War! An Appeal to the Vietnamese People, handwritten in Vietnamese by Ho Chi Minh. Photo courtesy of the Vietnam National Museum of History

What kinds of lives are worth living? What kinds of lives are we willing to sacrifice everything and die for? Where do we locate in the contemporary this unconditional commitment to a greater good, even at the expense of the violent obliteration of the individual selves?

Recently, I attended a northern Vietnamese folk religious ritual, called Hầu Đồng, organized by one of my neighbors in Hanoi. I remember whenever I had to go to this all-day ritual as a teenager, I would be quite bored and exhausted, frequently wandering around the temple to find some respite from the loud and spectacular festivities. But this time, armed with anthropological tools acquired from my Performance Studies training, I sat through and participated in the whole event with much wonderment, marveling at the smallest details about this social gathering.

Without succumbing to the ethnographic desire to excavate and describe this folk practice, I want to speak to my current fixation on the role of the main “performer” in this Hầu Đồng event. I put that word—performer—in quotation mark because she is not a professional performer per se; she is my next-door neighbor who sells fermented pork, who is called by gods and deities to perform for them several times each year. She does not have a choice; she is destined.

In the ritual, she offered herself up to dozens of gods and deities. One by one, they inhabited her body; she spoke as them and danced as them. She became a physical conduit for these higher beings to bless us participants. We bowed to her just as we would bow to a god, all of us devoting to something more powerful than ourselves.

In this collective moment of self-relinquishment, I remembered why I started dancing in the first place. I remembered the relentless commitment to the night, the powerful feeling of being taken by a force—both transcendent and immanent to the sociality of dancing. I remembered the absolute willingness to surrender myself, the wartime devotion that I was holding on in time of peace.

In dancing, I was trying to find Vietnam, to find that abstract something for which I’m willing to sacrifice everything. Dance, for me, has always been a matter of life and death.

Image Description:Dressed in all red, the main performer

in this Hầu Đồng ritual sits in front of a spectacular altar,

her back facing the camera. The large temple space is

meticulously and symmetrically framed by vibrant and

colorful flowers, fruits, and decorations.

Photo courtesy of the writer.

Photo of Anh Vo by Kyle b. co.

Image Description: A formal portrait of Anh,

an East Asian person, among colorful flowers and leaves.

Anh Vo is a Vietnamese dancer, writer, teacher, and activist. They create dances and produce texts about pornography and queer relations, about being and form, about identity and abstraction, about history and its colonial reality. Their writing focuses on experimental practices in contemporary dance and pornography.

anhqvo.com

Instagram: @anhqvo

Twitter: @Cult_Plastic

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/quocanh1995

Support

Paypal: quocanh1211@gmail.com

Venmo: Anh-Vo-8

Photo of Eva Yaa Asantewaa (she/her)

Image Description: In this selfie, taken in her home office,

Eva Yaa Asantewaa is wearing a black turtleneck sweater and

looking forward with a cheerful grin. She is a Black woman with luminous,

medium-dark skin and short gray hair. She’s positioned in front of a room

divider with an off-white basket-weave pattern.

Eva Yaa Asantewaa (she/her) is Editorial Director for Imagining: A Gibney Journal and, from 2018 through 2021, served as Gibney’s Senior Director of Curation. She won the 2017 Bessie Award for Outstanding Service to the Field of Dance as a veteran writer, curator and community educator. Since 1976, she has contributed writing on dance to Dance Magazine, The Village Voice, SoHo Weekly News, Gay City News, The Dance Enthusiast, Time Out New York and other publications and interviewed dance artists and advocates as host of two podcasts, Body and Soul and Serious Moonlight. She has blogged on the arts, with dance as a specialty, for InfiniteBody, and blogs on Tarot and other metaphysical subjects on hummingwitch.

Ms. Yaa Asantewaa joined the curatorial team for Danspace Project’s Platform 2016: Lost and Found and created the skeleton architecture, or the future of our worlds, an evening of group improvisation featuring 21 Black women and gender-nonconforming performers. Her cast was awarded a 2017 Bessie for Outstanding Performer. In 2018, Queer|Art established the Eva Yaa Asantewaa Grant for Queer Women(+) Dance Artists in her honor. In 2019, Yaa Asantewaa was a recipient of a BAX Arts & Artists in Progress Award. She is a member of the Dance/NYC Symposium Committee, Founding Director of Black Diaspora, and Founder of Black Curators in Dance and Performance.

A native New Yorker of Black Caribbean heritage, Eva makes her home in the East Village with her wife, Deborah. Sadly, their best-cat-ever Crystal traveled over the Rainbow Bridge on February 18, 2021.

Photo of Monica Nyenkan by Jakob Tillman

Image Description: Monica Nyenkan is the daughter

of African immigrants. She has dark brown eyes and hair.

In this photo, her hair has two-strand twists.

Monica Nyenkan is a Black queer community organizer and arts administrator hailing from Charlotte, NC. She graduated from Marymount Manhattan College, with a Bachelors in Interdisciplinary Studies. Currently based in Brooklyn, NY, her artistic and administrative work focuses on creating equitable solutions with and for historically marginalized communities in order to make art more accessible. In her free time, Monica loves to watch horror films and share meals with her friends and family. A fan of educator and historian Robin Kelley, Monica firmly believes the decolonization of our imaginations will help facilitate a more radical and inclusive way of living.

Photo of Sami Frost by Kylie Fowler

Image Description: A white woman with black

curly hair soft smiling into the camera head slightly

tilted to the right wearing a black strapless top and gold hoop earrings.

Sami Frost of Tampa, Florida, is currently pursuing a B.F.A. in Dance at Florida State University. She started dancing at the age of five at Judy’s Dance Academy. She continued her training at Next Generation Ballet, Brandon Ballet, Central Florida Dance Alliance, 5th Dimension Dance Center, and Howard W. Blake Performing Arts High School. Sami has trained with choreographers such as Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, Gwen Welliver, Ilana Goldman, Donna Uchizono, Layla Amis, etc. She’s been in works created by Ronald K. Brown, Anjali Austin, Jennifer Archibald, Carlos Dos Santos, Merce Cunningham, and more.

Previously, Sami was a touring assistant with Revel Dance convention, a contemporary teacher at 5th Dimension Dance Center, Song and Dance, and an apprentice in Tampa Modern Dance Company. She was chosen to present work at the American College Dance Association at FSU, the Outstanding Student Choreography Concert at the National High School Dance Festival, and the NewGrounds Dance Festival. In 2019, Sami was a dance intern at 621 Gallery, where she organized and facilitated artist collaborations, and is now the Center Project Intern at Gibney.

DISCLAIMER: Opinions expressed in Imagining: A Gibney Journal are the writers’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views, strategies or opinions of Gibney.