Imagining

A Gibney Journal

Issue 10

Letter from the editor

When last I sat down to write to you—preparing Imagining‘s March edition—I could not have known that the sudden prospect of World War III would come to replace COVID-19 as my daily worry.

As I sit here at my desk to write to you today, it is March 7th, twelve days since Vladimir Putin invaded the sovereign democratic nation of Ukraine, unleashing merciless violence on its people and raining destruction on its infrastructure and environment.

Russian forces have seized two nuclear power plants—including the toxic Chernobyl site—and have designs on a third.

Ukrainian families—from newborn babies to nonagenarian grannies—seek shelter in subway stations, while access to food, water, and medicine diminishes.

More than a million desperate refugees have fled to neighboring Poland, Hungary, and other countries.

A brave president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, stands his ground while pleading for assistance from our nation and its NATO allies.

And hearty resistance to Putin’s aggression rises in the streets of Ukraine’s embattled cities and in Russian cities, too, where Putin’s penchant for brutal oppression is news to hardly anyone.

By the time you hear from me again…well, who knows what will have happened?

In our third year of the pandemic—six million deaths later, while societies, states, cities, businesses large and small, and cultural industries whistle a happy little tune called “Return to Normalcy”—we now face even more uncertainty, a crisis of potential worldwide consequences. And, again, the powers that be seem unable to protect the innocent.

In this moment, I also witness and take comfort in the courage that still exists, the truth that still counters lies, the compassion and responsibility still not fully drained from a traumatized human race.

Every day, as we witness what has become of our precious and fragile world, we must ask: Where is my compassion? Where is my courage? What is my responsibility?

I believe the call and challenge to those qualities present themselves every day—at a great distance and quite near to us—and every mindful effort can be a worthy contribution.

Writing to you from “Little Ukraine” in New York’s East Village on Lenapehoking.

Eva Yaa Asantewaa

Editorial Director, Imagining: A Gibney Journal

Imagining Digital

Do not text me anymore.

Please seek therapy and heal.

This was the last text I sent to my mom in August 2021. Although our relationship has faced critical moments, it was different this time.

I am strong

I am a SuperCrip

My disability is my greatest strength

My dad sent me to the hospital in a coma when I was 4 or 5 years old. The beating was so bad that he left me almost blind. These facts were documented in my medical file, which my mother has refused to share for years and which has prevented me from clearly explaining my case to every ophthalmologist I have visited since then. The only thing I can share with the doctors are the memories that rest in my mind.

In August 2021, my mom sent me a text confessing that she had thrown my medical file in the trash. My file was unique and irreplaceable. My family, in an effort to cover up my dad’s violence, made up a story about what happened to my eyes. It was Central America during the 1980s. Patriarchy is protected and celebrated.

Let’s make a Pact of Oblivion

If someone asks about the child’s eyes

Say he had an accident with a chair

Repetition over the years becomes true

people forget

children forget

The story about how I became visually impaired has haunted me my whole life. That’s why disability and memory are very present in my work. In a map of my disability that I built based solely on memory, my dad’s attack took place sometime between 1984 and 1985. I had two surgeries between 1986 and 1987 to regain some of my sight in my left eye. Between 1988 and 1992, I visited many doctors to decide what to do with my blind right eye, which was dislocated and beginning to turn white from blindness. In 1993, I had the last surgery to place an intraocular lens and connect nerves between the eyes to correct astigmatism.

Don’t bother people with your crossed eyes

Focus and pretend you’re looking straight

You must practice eight hours a day

If your eyes hurt, think about how handsome you will look when your eyes are fixed

A couple of years ago, in my last visit to the ophthalmologist, I could not explain my surgeries to the doctor with dates and diagnoses, as usual. But I mentioned that in 1993 I had an intraocular lens inserted. My doctor smiled and said: You are like Robocop!

Image Description: Pencil portrait of Christopher as a child drawn by their husband, Neurodivergent artist Branden Charles Wallace. Surrounding the drawing are several vintage RoboCop stickers that Christopher found on eBay. Image courtesy of the artists.

BOOM! I felt electricity in my body. I haven’t heard someone call me “RoboCop” in years.

Do you remember the matinee at the movies?

The afternoons with your cousin

Popcorn, mini cokes in glass bottles

Joy

It wasn’t all bad, it wasn’t all bad

I saw Robocop in 1988. I could see some things on the giant screen in the cinema. My cousin would describe everything else I couldn’t see. I instantly fell in love with RoboCop: his metal armor that outlined his muscles, his huge feet, the heaviness of his body, his heavy breathing, the mystery of his half-exposed face, his lips, his human/computer voice, his physical strength, and the fact that he spoke only when it was absolutely necessary. I was only 8 years old but laconic people have always seemed sexy to me.

Robocop was a memory buried among decades of trauma and frustration. I did not remember that not everything was bad. It wasn’t all bad.

Memory interrupts,

Sometimes you need to live without interruptions

Children forget

People forget

Back in the doctor’s office, my ophthalmologist came closer to see my eyes, then opened the door and called his colleagues to come see me. Another ophthalmologist, a nurse, and the secretary entered the room. My doctor told them with wonder that I had an intraocular lens and that I was like RoboCop.

Using one of the most remembered phrases from the film, he told me, “They’ll fix you. They fix everything,” alluding to how my disability had been fixed.

I left the office with mixed emotions. On the one hand, the kid in me was happy because I had been compared to RoboCop. On the other hand, the detestable Freak Show in which I had just been the protagonist.

Everyone talks about the boy

In front of him

Behind him

Next to him

They call him “Crip”

They call him “a lost cause”

Everyone talks about the boy

But no one talks to the boy

In 1993, before I went into surgery for my intraocular lens surgery, my ophthalmologist came to see me. Someone told him about my obsession with Robocop. He brought me a package of stickers that included RoboCop shooting, RoboCop in a police badge, and RoboCop looking straight ahead. The package also included stickers of Officer Ann Lewis, ED-209 and Hophead. The doctor handed me my medical records and suggested placing the stickers around my photo, attached to the front of the folder. A photo with me facing front with my squinting eyes. That was the last time I saw my medical file. A few minutes later, the anesthesia kicked in, and I fell asleep. The surgery was intense and difficult. It took twelve hours and six months to recover at home.

When I went back to school, RoboCop 3 was just released in theaters. In the midst of the half-robot-half-human cop obsession and my recent half-robot-half-human surgery, everyone started calling me RoboCop. People made fun of me but I always took it as a compliment. RoboCop was sexy, confident, strong, and helpful to others. RoboCop and I had a lot in common:

RoboCop and I had a lot of traumatic surgeries.

RoboCop and I were violently attacked.

RoboCop and I are experiments.

RoboCop and I are disabled.

Robocop and I are SuperCrips!

I like being a SuperCrip, not because I have an intraocular lens but because my disability has made me stronger, more authentic, more generous and more original.

The boy no one talked to

started talking to the universe

To tell stories hidden in his memory

And the universe paid attention

The boy began to remember

Memory is complex. What I remember is different from what my mom remembers. We both experienced the same violence but we both survived it differently.

Trauma is complex. What I have healed my mom still hurts, and what hurts me is endless. My mom thought that getting rid of my medical file was getting rid of the memory of my dad. My disability is deeply linked to him. Talking about my disability is remembering him, and I don’t blame my mom for not wanting to do it.

In the Homecoming scene, when Robocop arrives at his house at 548 PrimRose Lane, where he lived with his family, we appreciate him entering empty spaces, armchairs covered in sheets, broken mugs and dried flowers. We appreciate how his scanner loses signal for a moment and flashbacks of his life take over. RoboCop remembers his family in a sporadic and fragmented way.

My memory is sporadic and fragmented. Sometimes while I’m walking down the street or while I’m on the train my brain loses signal for a moment and flashbacks of my life take over: I remember sitting next to my cousin at the movies, with popcorn, people screaming with excitement and the sexy human/computer RoboCop’s voice:

It wasn’t all bad.

It wasn’t all bad.

It’s strange. Most disabled people have negative experiences with their medical file. Trauma is complex. But I still dream of that folder with my photo on the front, my squinting eyes and RoboCop stickers adorning my face.

Memory is distracting and I try not to obsess over it. There are times when I find myself so distracted by the past that the present becomes a constant state of pause.

Nostalgia for my story

Nostalgia for history

It’s Sunday morning. Everyone sleeps, I make sure to turn down the volume on the TV so I don’t wake up my husband. It’s time to enjoy my weekly ritual: Cup of coffee in hand and I snuggle under my blanket. I hit the play button and RoboCop 1 starts. My husband bought it for me for $14.99 on Primetime. It still amazes me. I still want to be like him. He still stirs my emotions. This time I notice something important: Alex Murphy, whose mind was completely wiped when he was turned into RoboCop, near the end of the movie, regains his memories and free will.

I am a SuperCrip

Memory is my superpower

Memory embraces me

Memory sets me free

Free

Free

Free

Free.

Photo of Christopher “Unpezverde” Núñez courtesy of artist

Image Description: Christopher poses facing front and crossing

his arms in a SuperCrip gesture. He wears a vintage RoboCop

mask from the 1980s that he found on eBay.

Christopher “Unpezverde” Núñez (b. Costa Rica, of Nicaragua and Garifuna descent) is a Visually Impaired choreographer, dramaturg, and educator based in NYC. Núñez is a Princeton University Arts Fellow 2022-2024, a Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art Fellow, and a two-time recipient of the Emergency Grant by the Foundation for Contemporary Arts. His performances have been presented by The Joyce Theater, The Brooklyn Museum-The Immigrant Artist Biennale, The Kitchen, Danspace Project, Movement Research at The Judson Church, The Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, CUE Art Foundation, Battery Dance Festival, Performance Mix Festival and Dixon Place, among others. His work has been featured in The New York Times, The Brooklyn Rail, The Dance Enthusiast, and The Archive: The Leslie-Lohman Museum bi-annual journal. He has held residencies at Danspace Project, Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), The Kitchen, Movement Research, Center for Performance Research, New Dance Alliance, and Battery Dance Studios. As a performer, his most recent collaboration includes “Dressing Up for Civil Rights” by William Pope L, presented at The Museum of Modern Art. Núñez was invited by the NYC Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs to share his story as a disabled and formally undocumented immigrant choreographer during Immigrant Heritage Week 2020. Núñez received his green card in 2018 and continues to be an advocate for the rights of undocumented disabled immigrants. He holds a BFA in Science in Performing Arts from the National University of Costa Rica.

Noa: In one sentence, how would you define “dance technique?”

Nattie and Hollis: Forms and strategies for moving the body and tuning into sensation to prepare/open up possibilities.

* * * * *

This is a generous, idealistic definition. It looks toward the future of technique: a roadmap to retool the traditions we’ve inherited into something more expansive and sustainable. Over the past few years, Hollis and Nattie have been working to redefine technique through their teaching and performance work—meaning, this is not the definition that either of them grew up with.

Through movement scores and in-class discussions, Nattie and Hollis are picking apart the unspoken goals baked into the dance techniques that comprised their technical training. After taking their classes, I’ve identified a few key rules they are questioning:

- You repeat a movement to execute it perfectly on command.

- When you dance within a technique, you try to strip your body of all other habits and histories.

- You do not change the technique, you allow the technique to change you.

Hollis and Nattie are working to create movement scores and teaching practices that fight these assumptions. In their class, you repeat a movement to break it. Repetition is a method to move through emotional states, exorcize demons, and find new patterns. At other points, they encourage you to dig into your habits and honor your body’s history.

All movement influences—from the way your dad dances at family gatherings, to the moves you learned off YouTube when you were fifteen—are invited into the room. Like a kind of dance polytheism, they allow you to mix and match the techniques you’ve learned and observe how they interact in your body. Through all of this, they are investigating a question: what would it look like to dance as your whole self?

* * * * *

One score that encapsulates some of their explorations is called “Floppy Cunningham.” It’s a three-part improvisation. During the first round, you attempt to dance Cunningham technique as accurately and full-out as you are physically capable. During the second round, you pick a word that describes your natural movement (for Hollis and Nattie, it’s floppy), and commit to moving like that. Then in round three, you attempt to do both simultaneously.

It’s a score that holds hidden emotional layers. On one level, “Floppy Cunningham” participates in the same kind of hero worship it’s fighting. The score is meant to decenter technique by putting it on an equal level with your natural movement. Choosing Cunningham, however, is a reflection of Nattie and Hollis’ extensive formal training—and their particular affection for postmodern dance. Including Cunningham, even critically, reinforces the idea that a technique like Cunningham is something to which we should pay attention.

But, the setup of the score reveals something deeper, and sadder. “Floppy Cunningham” is a productive exercise because the movement qualities are opposites. Yet putting your natural movement in opposition to technique means placing yourself in a position of rejection.

Like many people, I ended up in experimental and postmodern dance because I flunked out of other techniques. For most of my dance training, I believed I would never succeed in dance because my body was incapable by design. All of the ableism, racism, and cissexism built into codified movement lineages resonates in the sentiment, “Your body is the opposite of this technique.” “Floppy Cunningham” picks at the uglier parts of technique, the rejection and discrimination that pushes people out of technical dance training.

* * * * *

The process of questioning dance technique is full of grief. Hollis and Nattie’s most recent performance work, O Fallen Angel, indulges in the somber side of their process. While their classes are full of self-deprecating jokes, the performance is earnest and occasionally painful to witness. For long stretches of time, their bodies sweat and shake as they try to accomplish impossible physical feats. High kicks, long jumps landing on one leg, slow deep pliés. Their goals become obscure as the movement blurs into a monotonous rhythm of attempt and defeat.

The stripped-down nature of O Fallen Angel is part of Nattie and Hollis’ signature aesthetic but, as a comment on dance technique, it leaves behind some of the most impactful elements of technical training.

Dance techniques come with lore, aesthetics, ideals. Half the fun of learning a technique comes from the stories and icons that are woven into the movement, building a tangible history out of an ephemeral art form. When I was younger, I loved technique class because I could walk into Horton or Ballet knowing that I shared a common language with the other dancers. Through the sheer force of repetition, techniques build communities across space and time.

Maybe that’s where the sadness is coming from in O Fallen Angel. Moving away from established techniques is lonely. What happens when you stop believing in the values imprinted on your body? Repetition, sweat, and effort, but for what? The loss of moving without knowing why.

* * * * *

Through their classes, Hollis and Nattie are building a new community—a support group for people to process this existential dread. As teachers, they are mindful of people’s varying backgrounds, but participating in a class that’s critical of technique is not as easy as breezing through a technique class.

When you dig into the particulars of dance training, you unearth the inequities of access and exposure in dance. The training we receive, especially in early childhood, is dictated by unfair circumstances: socioeconomic status, geography, the unknowable whims of our parents. Nattie and Hollis are working to question the techniques that rule the concert dance world, but they’re beginning to rub against the edges of that line of inquiry. Criticizing an inaccessible canon can only take you so far before it repeats the same pattern of inaccessibility.

The teenager in me wants to ask, “Why don’t you just leave? If this system is so flawed, why not do something else?” But as Nattie and Hollis’ scores show, bodies don’t work that way.

Training and its interaction with the body is wildly unpredictable. Some movement patterns leave in an instant, others stay for decades. Old habits get remixed through an ever-changing body—injuries, gravity, new patterns, daily currents of emotion, exhaustion, and hormones. Just as it’s impossible to keep a technique frozen and pristine inside yourself, it’s equally impossible to erase it entirely.

* * * * *

Noa: In one word, what do you wish for your relationship to dance technique to be?

Hollis and Nattie: Mercurial

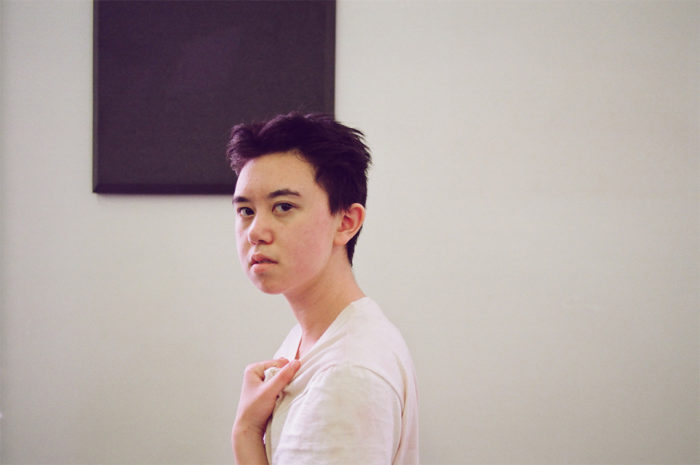

Photo of Noa Rui-Piin Weiss by Temi George

Image Description: A headshot of Noa Rui-Piin Weiss, a pale person

with short black hair parted down the middle. His head is turned to

the side to face the camera, and his hand is on his chest.

Noa Rui-Piin Weiss is a dancer, writer, and arts administrator. He is currently the post-baccalaureate fellow for The Movement Lab in the Milstein Center of Barnard College. Noa has performed works by Doug Varone, Bill T. Jones, Caroline Fermin, and Lucinda Childs, among others. He has presented choreography through Fertile Ground, Current Showcase (Take.5), SERIOUS PERFORMANCE!!!!, and recently collaborated with Adrienne Truscott on a dance film titled Jack of All Trades. Noa regularly contributes to The Brooklyn Rail and Culturebot, where he writes about performance. Most recently, Noa has discovered a passion for mash-ups, and would recommend “Nine-Inch Nails – Closer but it’s Funkytown by Lipps Inc.” mixed by William Maranci.

Support

Venmo: @noaweiss

Scan the QR code below:

XANDRA NUR CLARK: At the beginning of the pandemic, I remember we had a conversation over Zoom. I told you I wasn’t sure if I should be spending my time trying to write right now, or if I should just let myself do the other things I was doing. And I remember you said that you were actively trying not to be productive. You felt that if you tried to write something now, you would miss what was happening, and that if instead you just stayed present for the moment, you would eventually know what you needed to say, and then what you wrote would be much more meaningful. And this blew my mind a little—this sense of valuing process over product. It’s a challenge for me, because productivity is very much what I was raised to value.

MASHUQ MUSHTAQ DEEN: It’s what I was raised to value too. The way I was raised, there was never a sense that you’re good enough just as you are. And maybe my parents thought that I was good enough, but they never would’ve said it, because I think they were afraid that I would get lazy and not work, not have done my best. But on the other hand, I am very grateful that I was instilled with a strong work ethic.

XNC: Me too.

MMD: I had to learn how to slow down, and part of that journey for me was understanding that my self-worth does not come from my productivity. It’s something that I know now but also have to keep learning.

XNC: I really appreciate the ways you’ve helped me slow down. Like when I had my first residency last year, you said that the important thing is not to make yourself write all day but to just set aside the time when you’re not on your phone, not on email, and then maybe you’ll spend two hours of that time just staring out the window. But that’s part of the process. That’s useful time spent.

MMD: Was it? Useful to you, I mean?

XNC: Yeah! And the interesting thing that has happened for me over the last couple years since we first talked about this is that, ironically, I think I’ve been more productive in terms of the work I’ve made than I had been before. But it’s because I wasn’t trying to be productive. Which is really weird!

MMD: Weird and yet so true! I feel like it’s similar to acting, the sense that, “If I allow, it may be possible, but if I try, it won’t be possible.” You have to allow but not push. I also think people are afraid to be alone with themselves. When you slow down, when you don’t fill it with phones and emails and things, you start to be much more aware of your own shit. (He chuckles.) And I think that’s actually a really great place to be creative from, but a really frightening place for people to be in, and so they fill it with “doings.”

XNC: A couple things also happened that I didn’t even know were possible for me to do. Like my play Separated—I wrote a full, really solid draft in one week! And I never thought I could write a full-length play in one week. But it happened because I spent 15 months just letting it sit in the back of my head. And even when I sat down to write, it’s not like I had a plot mapped out; I didn’t know where it was going. I just had a question in my mind, and lived 15 months, and suddenly this play came out!

MMD: I feel like my best things have come out all of a sudden like that. Like my play Flood came out in 18 days and didn’t need many changes. And the things I effortfully create need to be changed so much. But in my mind, I still get caught up in the world we’re in that values productivity, so I begin to think crazy thoughts like, “If I can write a play in 18 days, then in 45 days—which is the length of my next residency—I can write three things!” But I’ll be lucky if I get a third of the way through the first thing.

XNC: I feel like a lot of the waiting is just creating space enough for the intuition to come through. It sometimes feels like the inspiration comes when I’m not even connected to myself so much as something much larger than myself. But I definitely can’t force that to happen.

MMD: I spend a lot of time wrestling with my ego to try and get it out of the way so that I can hear my “intuition,” as you say; I think of it as being able “to hear the music of the piece.” Sometimes I write a page, and my mind gets grandiose: “Ooh, I wrote a page! It’s such a good page! I’m going to win a Pulitzer!” But that’s my ego and my ego is a shitty writer. So I have to figure out how to dissolve that part of myself until it doesn’t matter anymore, until I can hear the music of the piece again. And of course the irony is that, if I really hear it, it’ll be a good piece, and maybe it will get recognition. But if I write for the purpose of recognition, it never will.

I think the oxymoronic thing of “I’m more productive when I’m not trying to be productive” is true in many facets of our careers. For instance, I get more opportunities when I don’t put so much importance on them. More people want to do my work when I’m curious about the world than when I seek approval from the gatekeepers. And yet everything around us tells us the world is scarce, there’s not enough, you must scrabble. And it’s very hard to constantly fight that.

XNC: There’s another thing that we haven’t talked about that feels connected to me. How does slowness and valuing process over product—which feels very anti-capitalistic to me—how do you reconcile that with the value of making radical change in our industry, and society in general? Should we be working towards rapid, radical change, or should we be taking things more slowly? I have been pushing for some changes in our industry that feel so urgent. And I also have been asking myself lately about the way we—especially in our institutions—are quickly firing this person and instituting this new policy and starting land acknowledgments and getting out a press release, without always taking the time to fully understand the changes and do them with care and with intention. The change feels necessary in so many ways and is long overdue. But is it sometimes happening in a productivity-focused, capitalistic way—to get to a resolution as fast as possible, instead of working through the muck of the process?

MMD: That’s a good question. Because part of capitalism is speed. Everything has to happen so fast. And on top of that, the thing about productivity is that we’re commodified, so it’s built into the system that we all treat each other in terms of “usefulness.” Like, “You’re no longer useful to me, you old white person, and so I can just throw you out.” It’s tricky, because we’re inherently trapped in the system as we’re trying to make change. I wish we would spend more time thinking, “What could a land acknowledgment look like?” On the other hand, just that theaters do it at all, of course, is kind of amazing in that we’re being verbal about things we’ve never talked about before. That’s great. I just question it when it begins to feel rote, when it starts to lose its meaning. So I wish there were more nuanced conversations, but they’re uncomfortable to have.

XNC: And again, that’s part of the slowness of creative work when you aim for process over product. It is very uncomfortable. It’s much more comfortable to just decide, “Well, I’m not getting any writing done, and I’m not going to just sit here staring out the window, so I’m going to…send an email!” instead of sitting with the discomfort, and moving through it, and then something will come.

MMD: It strikes me that the discomfort that we sit with is more frightening than the discomfort of beating ourselves up, which we do all the time. But, if we can be present for the discomfort, we are also present for the bits of joy that turn up. And they do turn up: when I was at a residency in Wyoming, where the sky was just so blue, I spent so much time just looking at it. And that blue ended up in my play, but it also ended up inside of me. It feels very magical when it’s all working. It’s humbling to be a part of.

XNC: It is. Once I’m in the flow and present for whatever story needs to come out, it feels amazing. It’s just getting there that’s hard. Even deciding to sit down at my desk and slow down and listen is hard. It seems like it should be easy! But it’s not.

Photo of Xandra Nur Clark by David Noles

Image Description: Playwright/performer Xandra Nur Clark grins at the camera.

The photo, taken a few years ago in a photography studio, captures them from the top of their head to their chest.

They are wearing a sleeveless navy blue top, but the color isn’t visible because the shot is in black and white.

They have curly dark brown hair down to their chin, and their skin is olive-toned.

Xandra Nur Clark (they/she) is a queer, biracial playwright, actor, journalist, community-builder, and all-around storyteller. Their work, which fuses theater and journalism, seeks to raise comfort levels around difference and urge public conversation forward around the “taboo.” They aim to cultivate intimate community by revealing what is relatable about the “other” and what is ultimately mysterious about the self. Xandra’s works include POLYLOGUES (2021 Colt Coeur Production, 2020 Kilroys List, 2020 Foundation for Contemporary Arts Grant); EVERYTHING YOU’RE TOLD (2021 Chesley/Bumbalo Playwriting Award); SEPARATED (2021 Semi-Finalist for O’Neill National Playwrights Conference); ANTHOLOGY: CROWN HEIGHTS (2016 Weeksville Heritage Center Production; 2016 Grants from Brooklyn Arts Council, Brooklyn Community Foundation, and Stanford Arts); and RETURNING HOME: VOICES FROM THE FRONT (2013 General Oliver P. Smith Award for Local Reporting from the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, 2012 Stanford University Production). Xandra is a 2018-19 Queer|Art Fellow (with mentorship from Mashuq Mushtaq Deen), a Company Member of Ensemble Studio Theatre and Poetic Theater, and a singer with folk choir Ukrainian Village Voices. As a journalist and radio producer, they have worked for StoryCorps, The Atlantic, and the BBC; had articles featured in Poynter, The San Francisco Chronicle, and KQED; and co-founded podcast True Story (over 6 million downloads). Xandra is an avid volunteer as a certified Crisis Counselor for the Anti-Violence Project’s 24/7 hotline. They are currently under commission from Ensemble Studio Theatre/Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. BA Theater, MA Journalism: Stanford University.

www.xandraclark.com

Instagram: @xandraclark

Twitter: @xandraclark

Support

Venmo: @xandraclark

PayPal: paypal.me/xandraclark

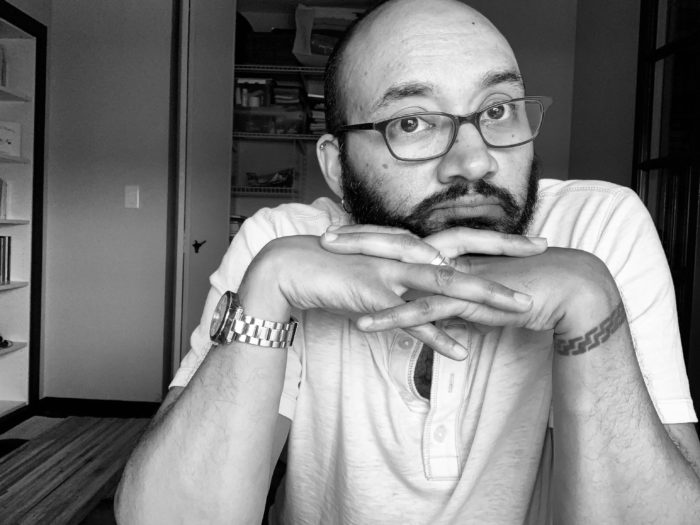

Photo of Mashuq Mushtaq Deen, courtesy of artist

Image Description: This is a black & white headshot of Mashuq Mushtaq Deen,

a balding man with facial hair, sitting at a desk, with his head resting on his clasped hands.

Mashuq Mushtaq Deen is a 2018 Lambda Literary Award winner, a 2020 Silver Medalist for India’s international Sulthan Padamsee Playwriting Prize, and the first runner up for the Woodward International Playwriting Prize. His publications include two plays, Draw The Circle (Dramatists Play Service) and The Betterment Society (Methuen Books), as well as short stories and essays, which have been published in JAAS, In The Margins, and elsewhere. His plays have been produced in NYC, DC, and Chapel Hill, NC. He is a resident playwright at New Dramatists, a core writer at the Playwrights Center in Minneapolis, and his work has been supported by the Sundance Institute at Ucross, Siena Art Institute (Italy), Blue Mountain Center, MacDowell, Bogliasco Foundation (Italy), and Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, among others. In his spare time he is a student of the guitar and of life.

www.mashuqmushtaqdeen.com

Instagram: @mashuqmushtaqdeen

Twitter: @mashuqdeen

Monica Nyenkan, Gibney Center Special Projects Manager, sat down with dance artist, bodyworker, and nurse devynn emory, to learn more about their new work, Cindy Sessions, which will premiere at Gibney on June 9-11. This conversation is a shortened, edited version of an extended Zoom conversation.

Monica Nyenkan: devynn, as a dance artist featured in Gibney’s Spotlight program series, you’re in the midst of creating new work while also working full-time as a registered nurse. How are you? How’s your heart? What have you been carrying?

devynn emory: Directly, I’m holding that my partner’s grandmother passed last night, which feels like divine timing. I’m working on a project right now around my two grandmothers who have passed in this last year of COVID. The project overall is about grandmother wisdom and stories from grandmothers passed down.

As you mentioned, I’m a full-time nurse in a hospital, so it’s been quite a rollercoaster working in COVID. I also work on my creative projects almost full-time, and I have a private practice as a healer and massage therapist. I’m juggling all three of those [roles], finding a way to weave and integrate it all into my creative process, as they are all speaking to the body.

Nyenkan: Can we talk about your creative process and how you’re weaving your healing practices and your experience as a nurse? How has that impacted your creative and collaborative processes?

emory: Right before the pandemic began, I was working in an Acute and Critical Care unit that was also serving as a Hospice unit. The unit experiences both emergent death and as well as slow transitional hospice. Previous to becoming a nurse, I have 20 years of experience practicing outside of medical training. I hold multiple licenses in Eastern medicine and bodywork, have had many teachers of various healing modalities, practice mediumship, and recently was certified as a holistic nurse. Entering the field of medical care in a “western” setting was a huge surprise to my system. To stay balanced, I started working on a somatic practice to release some of the grief from the patients who passed in my care that I found lingering in my body.

COVID began, and the number of people that I witnessed passing became incredibly overwhelming in numbers. COVID then shut down a premiere of a work I had invested five years into around the work as a nurse. It became very important for me to continue this focus while I worked in the hospital. I worked fourteen-hour shifts, three or four times a week. I would come home so exhausted, yet knew I needed to continue working on my show, creating a space as a way to honor the people who have passed in a more respectful way than the hasty way we’re dealing with in the hospital.

Photo courtesy of devynn emory

So, I made the canceled work into a film which became Part 1 of a trilogy, deadbird, and its touring grief altar and land project, can anybody help me hold this body. Becoming a COVID nurse is an isolating experience, yet I wasn’t alone in loss. This grief in nursing, escalated by COVID, created a more concentrated universal experience of loss, and I felt called to create more dialogue around it, bridging my experience as a nurse to my other communities. To keep the performers and audience safe, the film toured virtually, and I collaborated with local artists in multiple cities who tended an altar outside. This work invited a practice of spending more time with land, making an offering to the land, while having the land hold us. In collaborating with the land…the land that will be holding the bodies who have passed, it only makes sense to build more connection here as we stay in relationship to our loved ones, their loved ones, and their loved ones. This work, as I mentioned, is part of the #mymannykinfriends trilogy, and I’m currently working on part 2.

Right now, there are a few iterations called Grandmother Cindy that will then become Cindy Sessions at Gibney as part of the Spotlight series. It’s a continuation of a series centering medical mannequins in transition. It is a dance film with virtual engagement and potentially will have a live component. Cindy is the mannequin and center of this show. Medical mannequins have become my focus of this trilogy and are often the main dancer and collaborator. Cindy is a grandmother who is representing both of my grandmothers that have passed in COVID. I have also spent time reviewing the work of The 13 Indigenous Council of Grandmothers- a global council of grandmothers, as well as woven in stories from grandmothers of friends in my community around the themes of love, loss, and land. Cindy will share stories on those three topics with all of us. Currently, we’re losing a lot of our elders, and we’re gaining a lot of ancestors. As a way to honor them, I’d like to share their stories as a way to practice a continued connection, pulling their lessons into the paths I walk.

Nyenkan: Your previous work, deadbird, and the second project of this trilogy, Cindy Sessions, thread together the theme of grief, how we process grief, and ancestor reverence in a way that seems almost casual. Like a casual ritual. Could you talk about creating a container to process grief, bringing it Earthside, and facilitating it for others?

emory: This phrase that you use, “casual ritual,” is interesting. I believe that we practice death and transition (and I mean transition of any kind), in daily ways. If we are paying attention, the natural world around us is decomposing and renewing all the time. Where I am in the Northeast of the US, we’re privileged enough to also witness changes of seasons quite frequently. These more-than-human rhythms are also part of our human shifts. We transition constantly. If we can gather around the same flame—the concept of the body deteriorating daily and over time—then perhaps it’s not such a shock when a body transitions and passes. I want this honorable moment to be accessible to everybody, to unravel some of the stigma. Perhaps this then leads to less suffering and more invitation for us to be present with one another’s bodies, including our own bodies, living a more embodied and celebrated life. Here in Northern America, we are inundated with white capitalist insistent messaging, disconnecting us from our own bodies and others. I practice inviting us back to our bodies, welcoming us home.

When I zoom out, I am weaving a thread for myself around my practice of communicating to the spirit realm, which is something I’ve had a connection to since I was a child. I didn’t realize this wasn’t a common thread for everyone. When I became a nurse, I wasn’t prepared for how often this connection would occur while I was in the hospital setting. With the frequency of people passing in that building, I had a huge influx of people reaching me on their way to the Spirit world. Part of this trilogy is processing the bridge of Spirit work to nursing in conflict and overlap with my connection as a healer while finding a home for it all in performance. This aligns with my calling to open conversation about death and dying, ideally before the moment of crisis. I witness and regularly support family systems at the bedside in total surprise about what death looks like. Why is one of the most beautiful transitions of life often kept a secret until it occurs?

Cindy Sessions will invite the audience into an unveiling, behind-the-scenes care for someone as they’re transitioning. I believe I keep returning to building a vision or dream of an ideal care team as a way of being with a body in transition that I feel we all deserve. Witnessing a Spirit leaving a body is one of the most honorable experiences of my life. In Cindy Sessions, the audience is invited to witness a treatment session with Grandmother Cindy. The cast includes a care team including myself, Joseph Pierce from can anybody help me hold this body, Elisa Harkins, an incredible vocalist who has offered a prayer, and Quinha Faria, an installation artist who fabricated incredible, larger-than-life ancestors.

Nyenkan: Can you talk about what it’s like to collaborate with a live person and also with a mannequin? How is this collaboration different from that of your previous piece, deadbird?

emory: Manny is the main focus of deadbird, and Cindy is the main focus of Cindy Sessions. Part of that is because of safety and COVID, and part of it is because these medical mannequins hold the essence of a lot of my questions. They are in-between beings, the essence of transition. In my body as a mixed-race person, as a trans person, I feel relational vibrancy between myself and these medical mannequins that are also bridging or inhabiting multiple spaces. They’re not of this realm, but they’re both uncanny and realistic. We are both walking along various edges. I did work with live musicians and dancers before deadbird became a film, and I miss it. Joseph and I have recently rehearsed in person with the film crew after extensive testing. Having company in caring for Cindy’s body felt like a returning. I feel a lot less lonely after almost three years of COVID nursing, creating even deeper dreams for care work. To be next to someone I really trust while taking intentional time tending to Cindy’s body practicing medicine in alignment with another feels really healing right now.

Nyenkan: What is one thing you’d like the audience to walk away with after engaging with Cindy Sessions?

emory: I’d like for the audience to walk away after an experience of slowing down, with a sense of allowance to reconnect to their bodies and others in this durational span of grief. Part One invited folks outdoors to make an offering at an altar. Some people stayed for hours. It was often the first time people were coming out of their houses to be less alone in their experience. Folks can now access the film or the altar practice online if they missed the tour. Cindy Sessions is an invitation to remember that while the world pushes on with increased pressure and urgency, may we carry a wiser way. Listening to Grandmother stories in Cindy Sessions, reminds us to center the knowledge of love, loss, and land. You are invited to one story, or all three. For example- you can come on a Monday and listen to her speak about love, on a Tuesday about loss, and on a Thursday about land. This trilogy recognizes oral history and the power of storytelling, a way of slowing down and hearing from our elders. I find us younger folks internalize messaging around the capitalist notions of new thought on a faster timeline. Our grandmothers have done a lot of work already. The stories passed down around love, loss, and land…I mean…what else is there to talk about? If I were to imagine us sitting down around a fire to hear stories, those are the themes that I want to foreground and remember as I’m moving in community with others.

Nyenkan: Revisiting your thought about the mannequin as a place of transition, the larger picture of COVID is one of transition as well. As you create this piece, how are you tackling the theme of transition and also allowing for things to be permanent? How are you making space for things that will never change?

emory: There is a spoken, and sometimes unspoken, understanding that transness is a fluid space, an unknown space. I’m arguing that it is, in fact, known. For me, it’s a centering space. Because I’m mixed and trans, transitional space is the most familiar space to me. I live here, making it more familiar to me than an argued fixed point. This space is valid known space, one that doesn’t rely on others’ definitions of fixed. Transitional space can create fear in people who feel unease with uncertainty or their concept of such. Liminal space is the most comfortable place I could be. It is not only of relevance but of vibrancy and vitality, a concrete and valuable space.

Cindy Sessions premieres online from June 9 to 11.

For more information please visit https://gibneydance.org/event/spotlight-devynn-emory/2022-06-09/

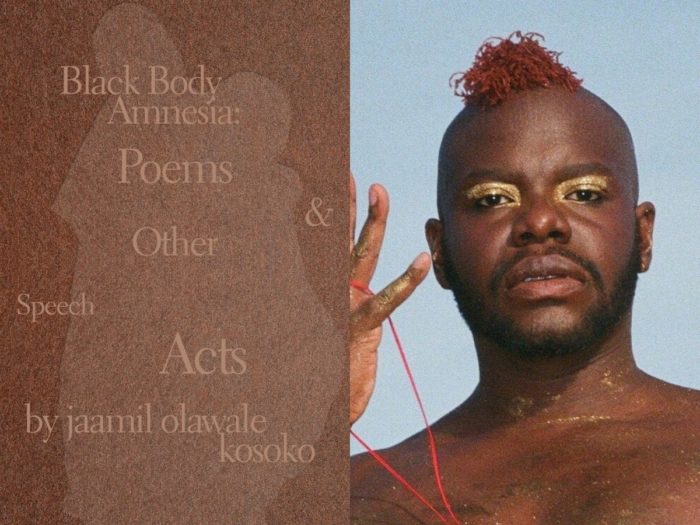

Photo of jaamil olawale kosoko by Nile Harris

As I read jaamil olawale kosoko’s Black Body Amnesia: Poems & Other Speech Acts, I suddenly sense a parallel experience in which I’m perceiving New York City as a physical and energetic grid, horizontal and vertical, where any sincere attempt at human:spiritual expansion is pinched:penzaied, and certain artists have left:must leave: are leaving in order to respond to a higher, more urgent calling. Your mileage may vary but, as I read on, I’m sensing kosoko (they/he/she/jlov) lifting us clear of that restrictive grid which is surely not just a metropolitan grid but a grid from sea to shining sea.

This starts early on, where kosoko throws out a challenge to “foreget.”

To reclaim your humanity.

To “radically center your own cultures, languages, and economies of care.”

“Foreget to stop bankrupting yourself.”

Foreget “to re-inherit yourself.” (1)

By trade, I am a crafter of words, but I have never imagined so shamanic a reworking of the verb forget. I am galvanized—and grateful.

I know quite a bit about bankrupting myself, and I want to know more about re-inheriting myself.

kosoko’s work, here and in their performances, insists on blurring sharp, Western-conceived edges between past, present, and future. So, I’m wondering if the trendy “Afrofuturistic” might fall short of being the most telling term for Black:queerness that permeates space:time.

In kosoko’s poems, there’s also no dividing line between tenderness and strength as time rushes through the body:psyche of a child:man. There are things that should not be part of a child’s experience, but we are Black in the US of A, and that has been true from Day One, and here we are.

I see no coincidence when I discover—after I’d casually pushed a small slip of notepaper between pages, awaiting notes for this essay—that the slip has landed on “Omen,” which begins on pinkish-beige page 30. The poem opens this way:

The spirits of the dead

are returning more often.

And you know what that implies. Spirits of the ancestors rest still, in confidence, when all is going well. But when they’re moving….!

Later on, kosoko warns us,

It’s a sign not to be ignored

when the past pushes further

into the present than the present,

when memories

and premonitions parallel,

when the ghosts speak back

the way they do now. (2)

Photo courtesy of New York Live Arts

kosoko’s poetry and performance texts evidence birth:death:in-between at every turn of an everpresent in which Lucifer’s “desert thirst” for Black blood is deep. There’s danger from first hint of life to last flicker. Poems like “Mama: a litany,” “Ectopic,” “Pushed,” and “Dogfight” chase after one another, infused with an alchemical mix of sex and brutality. These poems are inseparable siblings. You read, breathless, and turn the page, and…no, wait! There’s always more. Always.

For kosoko, memory is a thing to be manipulated so it can illuminate, but not strangle, Black life. The book’s final words, drawn from our warrior ancestor Audre Lorde, say it well:

If you can’t change reality, change your perception of it.

The book—edited by Dahlia (Dixon) Li and Rachel Valinsky of Wendy’s Subway and designed by Omnivore—has been born into this world as a collage of textual and visual media; pages of variegated thickness, texture, and tint; text in different fonts, pitched in one direction or another. kosoko’s poems (as well as other materials contributed by invited essayists or conversants) are rendered in customary profile view on the page. For kosoko’s performance texts and lyrics—in white fonts on thick camel-brown paper—you must turn the book sideways as if studying a racy centerfold.

Always, kosoko asks you to step out of the habitual and join them in floating free where there’s a lot of a lot going on even if—as in the words of writer Nadine George-Graves, whose essay reflects on their friendship—”you have no idea what he is doing” and “(and, be honest, you don’t really understand it anyway.)” (3)

I remember times of not understanding it anyway, so, I chuckle along with George-Graves. I also remember once involving the word “shaman” when someone asked me what I thought of kosoko. Time:distance from them and their work—and now reading this book—reinforces the truth of that initial impression: shaman. And how many of us can say we’re really all up in what a shaman is doing? Even the results of that doing might not hit us right away.

The record of a March 2020 conversation with Bill T. Jones (4) yields another relevant word–”ministry.” It’s getting at the same thing, from a different cultural point of view and method. And then, talking with Ashley Ferro-Murray, kosoko speaks of offering up their psyche:body experience as “the spiritual work and labor of reprogramming one’s own infrastructure.” (5) Doing that in public is a transparent, personal act of self-healing with, as I see it further, implications and potential for one’s community. kosoko’s shamanic ministry, which originates in the self and its history, intervenes as we, Blacknation, now face a resurgent movement to obscure the history of how our ancestors suffered under white brutality:how they resisted:how they emerged:how they created extraordinariness under extraordinary duress.

For all this, kosoko remains transparent:elusive in their/his/her/jlov appearances in this book—a figure there or not there, often identifiable only in a hazy way, if at all. I want to point to one image in particular.

It’s in the latter part of the book, straddling two pages. The spine of the book splits kosoko’s face down the middle, a rare image in which the performer gazes directly into the reader’s eyes and in which kosoko’s eyes are not obscured by a blindfold or fabulous shades or an engulfing shroud.

The two photo pages are awash in subtly variegated charcoal. The faint entry of light into that overall dismal tone allows the reader enough detail to detect a hooded being gazing back warily, thinking complicated thoughts.

Soon after finishing Black Body Amnesia, I return to reading the late David Wagoner’s After the Point of No Return, open it to my bookmark for the next poem, and find myself at “Life Class.”

…She’s holding still

but she’s being paid to hold still, the best defense

Some creatures have against death: to disappear,

to become whatever surrounds them. when they move,

they’re lost…” (6)

Wagoner’s “she” is, of course, a life model at work in an art class—flesh-naked, soul-hidden. Yet this poem brings me back to kosoko’s shapeshifting—kosoko’s slipping into the camouflage of stage or page; reappearing miles or aeons from where they were last seen; getting lost, in this dangerous time, as perhaps the safest and best way to find themselves.

-

“A Notion on Foregetting,” jaamil olawale kosoko, Black Body Amnesia: Poems & Other Speech Acts, p. 13

-

“Omen,” jaamil olawale kosoko, BBA, pp. 30-31

-

“Untitled,” Nadine George-Graves, BBA, pp. 206 and 207

-

“Testify: Conversation with Bill T. Jones,” BBA, pp. 92-99

-

“The Glitches We Reach Through: Conversation with Ashley Ferro-Murray, BBA. p. 106

-

“Life Class,” David Wagoner, After the Point of No Return, p. 98

Photo of Eva Yaa Asantewaa (she/her)

Image Description: In this selfie, taken in her home office,

Eva Yaa Asantewaa is wearing a black turtleneck sweater and

looking forward with a cheerful grin. She is a Black woman with luminous,

medium-dark skin and short gray hair. She’s positioned in front of a room

divider with an off-white basket-weave pattern.

Eva Yaa Asantewaa (she/her) is Editorial Director for Imagining: A Gibney Journal and, from 2018 through 2021, served as Gibney’s Senior Director of Curation. She won the 2017 Bessie Award for Outstanding Service to the Field of Dance as a veteran writer, curator and community educator. Since 1976, she has contributed writing on dance to Dance Magazine, The Village Voice, SoHo Weekly News, Gay City News, The Dance Enthusiast, Time Out New York and other publications and interviewed dance artists and advocates as host of two podcasts, Body and Soul and Serious Moonlight. She has blogged on the arts, with dance as a specialty, for InfiniteBody, and blogs on Tarot and other metaphysical subjects on hummingwitch.

Ms. Yaa Asantewaa joined the curatorial team for Danspace Project’s Platform 2016: Lost and Found and created the skeleton architecture, or the future of our worlds, an evening of group improvisation featuring 21 Black women and gender-nonconforming performers. Her cast was awarded a 2017 Bessie for Outstanding Performer. In 2018, Queer|Art established the Eva Yaa Asantewaa Grant for Queer Women(+) Dance Artists in her honor. In 2019, Yaa Asantewaa was a recipient of a BAX Arts & Artists in Progress Award. She is a member of the Dance/NYC Symposium Committee, Founding Director of Black Diaspora, and Founder of Black Curators in Dance and Performance.

A native New Yorker of Black Caribbean heritage, Eva makes her home in the East Village with her wife, Deborah. Sadly, their best-cat-ever Crystal traveled over the Rainbow Bridge on February 18, 2021.

Photo of Monica Nyenkan by Jakob Tillman

Image Description: Monica Nyenkan is the daughter

of African immigrants. She has dark brown eyes and hair.

In this photo, her hair has two-strand twists.

Monica Nyenkan (flexible pronouns) is a Black queer artist, administrator, and emerging curator from Charlotte, NC. Graduating from Marymount Manhattan College, Monica received her Bachelor’s degree in Interdisciplinary Studies, concentrating on administration for the visual & performing arts.

Currently based in Brooklyn, Monica has interned and worked with Rachel Uffner Gallery, Gallim Dance, Ballet Tech Foundation, Movement Research, and 651 ARTS. She’s produced community-based engagements and art events throughout NYC for the last five years. She acted as a consultant and advisor to an award-winning project, LINKt: a dance film. Most notably, Monica co-curated WANGARI, a pop-up art exhibition focusing on climate change, with the Brooklyn-based collective Womanist Action Network.

Monica currently works as the Gibney Center Special Projects Manager, managing programs such as Black Diaspora and Imagining Digital. In her free time, Monica loves to watch horror films and spend time with friends and family.

Photo of Sami Frost by Kylie Fowler

Image Description: A white woman with black

curly hair soft smiling into the camera head slightly

tilted to the right wearing a black strapless top and gold hoop earrings.

Sami Frost of Tampa, Florida, is currently pursuing a B.F.A. in Dance at Florida State University. She started dancing at the age of five at Judy’s Dance Academy. She continued her training at Next Generation Ballet, Brandon Ballet, Central Florida Dance Alliance, 5th Dimension Dance Center, and Howard W. Blake Performing Arts High School. Sami has trained with choreographers such as Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, Gwen Welliver, Ilana Goldman, Donna Uchizono, Layla Amis, etc. She’s been in works created by Ronald K. Brown, Anjali Austin, Jennifer Archibald, Carlos Dos Santos, Merce Cunningham, and more.

Previously, Sami was a touring assistant with Revel Dance convention, a contemporary teacher at 5th Dimension Dance Center, Song and Dance, and an apprentice in Tampa Modern Dance Company. She was chosen to present work at the American College Dance Association at FSU, the Outstanding Student Choreography Concert at the National High School Dance Festival, and the NewGrounds Dance Festival. In 2019, Sami was a dance intern at 621 Gallery, where she organized and facilitated artist collaborations, and is now the Center Project Intern at Gibney.

DISCLAIMER: Opinions expressed in Imagining: A Gibney Journal are the writers’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views, strategies or opinions of Gibney.