Imagining

A Gibney Journal

Issue 12

Letter from the editor

As you read this, it’s November, but I’m writing to you just after Labor Day in anticipation of a great new presentation year of Imagining Digital lectures, conversations, and WORD! performances; the exciting expansion of the Black Diaspora artist residency and public discourse program; and publication of this journal’s September 2022 issue.

For New York City’s arts communities and audiences, each autumn comes around as a time of fresh hope and high energy. This one, following years of losses and uncertainty, feels fraught for both our city’s economic health and the overall well-being of its artists and arts institutions. There’s so much riding on this one.

In recent weeks, Managing Editor Monica Nyenkan and I learned that, with Fiscal Year 24, Gibney will discontinue all of its digital programming and refocus on in-person performances curated by new Artistic Director Nigel Campbell as well as a slate of residencies. As part of this broad restructuring, Imagining: A Gibney Journal will cease publication after our May 2023 issue.

Sad news, I know, but I am heartened to tell you that Gibney management and I agree that existing and upcoming issues of the journal should be archived, and Gina Gibney has promised to look into a way to do just that.

When I think of the numerous writers commissioned for essays since Imagining’s 2020 launch, I’m deeply grateful for all they’ve shared–informative, lively, intimate, inspiring work. As a writer and editor, I’ve been educated and moved by this outstanding work. I want it to remain available to its creators and accessible to readers and researchers for many years to come.

If you have appreciated Imagining, it would do our hearts good to hear from you. Monica and I welcome your messages at eva@gibneydance.org and monica@gibneydance.org.

We have so loved this work, and we now look ahead to producing three more issues for you–January, March, and May. We hope you’re looking forward to reading and enjoying them!

Eva Yaa Asantewaa

Founding Editorial Director, Imagining: A Gibney Journal

Imagining Digital

In my twenties, I was living in Minneapolis and working as a professional dancer on projects with choreographers making queer works with complex social commentaries. I was proud. Not only was I working consistently as a dancer, I found a group of like-minded folks whose politics and aesthetics jived with mine and, in those formative years, greatly influenced me. I was fulfilling my adolescent dream of becoming a professional dancer, and I was dancing in work I actually liked.

By this point, my girlfriend and I had broken up, and I was living alone with my cat in a basement apartment for $500 a month. I was making $65 monthly car payments to my parents on a $3,900 loan they gave me to buy a champagne-colored 1997 VW Jetta with a moonroof. On Pride weekend, I found a unique (at the time) bumper sticker that said “Question Gender,” and I slapped it on the car. Again, I was proud. Living a dream.

Except I wasn’t really making ends meet financially. Thanks to my parents and deceased grandparents, I had no undergraduate student loans. Nevertheless, I was accumulating credit card debt. I was paying for groceries, phone, internet, car insurance, gas, utilities, cat food, kitty litter, and alcohol. I definitely wasn’t saving money. I had a great job working as a floor manager/host of a woman-owned, farm-to-table restaurant (a novelty at the time). I had basic health insurance and ample unpaid time off as long as I got my shifts covered which meant I could rehearse and perform with minimal scheduling stress. The income that came from my dance work helped offset my monthly expenses, but I didn’t count on it for that purpose. I figured I should take care of my financial needs from my restaurant job and anything that came from my dancing was a bonus. I thought of it this way because I was happy doing the kind of dance work I was doing. I had no interest in taking other, more commercial dance gigs that might help pay the bills. (As if those jobs would have hired me? As if those jobs paid the bills?)

But this set-up led to some personal, maybe existential, confusion. The opportunity arose to apply for an artist fellowship in recognition of my work as a dancer, and I was stuck. Was I worthy of this fellowship? I couldn’t be eligible for this. I don’t make my living as a dancer. Surely they mean to support “real” dancers who make their entire living from dancing. No doubt there were dancers far worse off than I who needed this support. This fellowship money needs to go to professional dancers who are struggling to make ends meet. Somehow I was unable to see myself in that category.

This perception problem was partly because I had dancer/choreographer friends who didn’t have to work day or night jobs. I didn’t know the particulars of how they managed their lives; it never felt right to ask. Based on what I did know of them, I assumed they had some family support. One artist I knew was able to buy a house because they got a large, one-time, unrestricted grant, thereby establishing a relatively cheap mortgage and investment nest egg that I imagined set them up for the rest of their lives. Keeping their income low, they could receive government support for health insurance, heating, and other major home repair needs. They and other artists in seemingly similar circumstances possessed a willingness (and most likely, class-related ability) to exist in what I perceived to be a precarious state of un-guaranteed income. Dance artists who seemed to be surviving on grants, commissions, sporadic teaching gigs, and performance opportunities made me feel like they were the “real” artists. In contrast, I wasn’t a “real” artist because I chose to find some level of security in regular paychecks from non-dance work.

When I confided in one of these friends that I felt like I wasn’t eligible for a fellowship despite the fact that I was working regularly as a paid dancer, they were surprised and helped me see this gross error of perception. Why did I think that funders wouldn’t take me seriously as a dancer because I didn’t meet the criteria of a “starving artist?” I didn’t identify with that image. In fact I made conscious choices to protect myself from it. But somehow I still couldn’t escape the idea that the system wasn’t meant to support me because I (necessarily) worked a job to support myself.

Fast forward almost two decades to last month when I was talking with a dance artist who also works as a physical therapist. I heard her voice nearly the same thought process that I experienced years earlier; she didn’t think she was eligible for a substantial grant for her choreography because she supports herself through non-dance related income. It pained me to hear that this perception still stands, especially since “side hustle” rhetorics have become so prevalent. (By the way, she ended up applying anyway and was granted that substantial support for her choreography.)

We know that dance artists have always pieced their incomes together from various sources, sharing living expenses with others, and relying on families, spouses, and patrons to help pay the bills. So why is this reality still shrouded? Why do some of us think we aren’t professionals when this is, in fact, a longstanding reality of our field? This is pretty much how it looks. This is how it has always looked.

Dance teachers who had exciting careers as performers rarely tell us how they worked other jobs and shared rooms with friends in tiny apartments during those years. And/or they don’t mention that they didn’t have to work additional jobs because their families or spouses supported them. Dance historians often gloss over the lived experiences of dance artists and choreographers when they chronicle and analyze the work that’s been made. We rarely get to understand what dancers’ day-to-day lives were like, how they managed, how they put food on the table, and who they shared that table with. And we rarely connect those lived experiences with the work they produced. Journalists profiling dancers and choreographers also tend to paint narrow pictures of the trajectory of someone’s career. Maybe we learn a choreographer didn’t get their “break” until they were 40, but we don’t explicitly hear how they were able to toil away, rehearsing and making dances while living in expensive New York City (for example) up until that point. Could it be that they worked other jobs and had additional support? Most likely, yes.

If we don’t name it, we are left to fill in the gaps with our skewed perceptions. The competition in this field is so thick that we might assume we are to blame for our inability to support ourselves through our art. That we aren’t strong enough, brilliant enough, or connected enough to be relevant. We end up perpetuating the myth of meritocracy. If we carry on with this charade—omitting public and private conversations around the various realities of dancers’ experiences—young dance artists will continue to enter the professional field disillusioned, thinking they aren’t “real” professionals if they can’t make enough money to support themselves from their dance work alone. When the reality is, this was never the case for most dancers. At the same time, we should explicitly acknowledge that there is no universal experience or perception of what it means to be a professional dancer or choreographer. We know that our race, class, ability, and gender all deeply and personally affect our access to professional work, be it dance or non-dance employment. And our various identities directly affect our perceptions of worth, entitlement, success, and security.

Dance-adjacent jobs have always been acceptable in the picture of how dancers and choreographers can make ends meet. Teaching dance and other body-based techniques is a classic way to make a living. The increase in MFAs and PhDs in dance scholarship and praxis finds artists/scholars working in academia and applying for the same grants and performance opportunities as everyone else. It is also more acceptable now to work as arts administrators in the same organizations and institutions we orbit without the stigma that we are somehow less serious than other dancers or the threat of professional blockade and conflicts of interest.

I’d like to add to this list of “acceptable” side careers by normalizing other types of work. In case you haven’t heard it before, let me take this opportunity to name that there are professional dancers involved in exciting and powerful work who are also nurses, lawyers, accountants, editors, bakers, biochemists, bartenders, life coaches, real estate agents, therapists, security guards, and so forth. No, these dancers are not automatically “out of shape” or more prone to injuries because they work other jobs. They can be just as, if not more, efficient, stimulated, curious, and in tune with their bodies and creative processes as dancers who work dance-adjacent jobs or no additional job whatsoever. In fact, it’s hard to overstate the benefit of having meaningful work experiences in fields outside of dance. We become more well-rounded citizens, more engaged in local politics, finances, healthcare, activism, etc.

I’m not suggesting we perpetuate the old “career to fall back on” adage. In addition to reliable and substantial universal basic income, I’m advocating for the acknowledgement, dare celebration of, “careers we also excel at.” This is not because we failed to “make it” as dancers— if “making it” means earning all your necessary income from dance without additional support from a community of loved ones— but because we are smart, interested, and skilled at any number of additional careers. We are actually that good. It is also okay (nay, crucial) to enjoy our other work. We can thrive at our other jobs and thrive as dancers.

A mother (who is also a dancer) recently asked me what advice she should give her exceptionally smart and talented high school daughter regarding her college career choices. She wants to keep studying dance and build a career as a dancer after she graduates, but she is also really interested in STEM. The implied problem here is that these fields are incompatible. I’m not convinced that is true. The implied question is, can she do both? Absolutely, she can.

Ways to help make dance artists’ realities more explicit:

Artists:

If you haven’t already, update your bios to include your non-dance work and shout out your roommates and/or families for sharing the bills. Just as we want to hear where you studied and what other projects you have done, we want to know how you make your life work.

Journalists:

Start printing the details of artists’ lived circumstances so the general public can understand, right alongside cultural context and artistic genius, the conditions that brought this work to fruition and these artists to this point in their careers. Printing “the hows” will help normalize our realities.

Historians and scholars:

Include the nitty gritty details of artists’ lived experiences in the contextualization of their work. Help us understand the circumstances. Make the economics, politics, and social infrastructures of the artists under consideration explicitly clear. Help us connect the lineages of their experiences with ours.

Funders and Grant makers:

Continue to check your language for assumptions and restrictions around eligibility criteria. Show us that you understand the complex realities of our experiences as dancers and choreographers in the field. Let us know who you think needs support and why. In the articulation of that criteria, help us eradicate the paradigm of the “starving artist” by acknowledging that we thrive in a multitude of ways. And continue to support us wholeheartedly.

Image Description: A white woman with shaggy, dirty blonde hair, dark blue eyes, and wearing a black button up shirt, softly smiles at the camera. Her head rests in her hand.

Photo by Christine Wallers.

Joanna Furnans is a dance artist, writer, and administrator. Her work has been supported by a MANCC Forward Dialogues Laboratory, a Schonberg Offshore Creation Residency at the Yard, an Institutional Incubator Sponsorship at High Concept Labs, a Chicago Dancemaker’s Forum Lab Artist Award, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the Illinois Arts Council Agency, the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE), the Chicago Dancers’ Fund, the Chicago Moving Company, Links Hall, and the Walker Art Center’s Choreographer’s Evening. In 2016, Joanna co-founded the Performance Response Journal, an online platform for writing about dance and hybrid performance in Chicago. To date, this grassroots endeavor has engaged over forty Chicago-based writers and published over eighty creative and critical responses to dance and performance in the city. Her recent graduate research at the University of New Mexico focused on the lived experiences of marginalized, independent dance artists working outside of New York City in the era of global neoliberalism. While pursuing her graduate studies, Furnans held positions in the university’s Division for Equity & Inclusion and the LGBTQ and Women’s Resource Centers.

Instagram

@joannafurnInstagram

A “Black woman’s body was never hers alone.”

—Fannie Lou Hamer

Picture a cemetery where over half the children buried are under two years old.

Imagine if nearly all the fractures found in the deceased happened near the time of the person’s death. (Meaning the fracture—frequently in the skull—had played a part in that individual’s demise.) Imagine having known a young woman who had over 30 of her bones broken around the time of her death. Imagine having heard about a middle-aged man who also suffered 20 fractures around the time of his demise. Imagine having seen a pre-teen with 18 broken bones—both arms and legs, her/his head and her/his pelvis. Imagine having known a woman, who was barely five feet tall, who had been shot in her ribs and suffered repeated blunt force trauma to her face. Imagine having befriended people who worked so hard their muscles separated from their bones. Think about your child being put to work before the age of six. And what if you had been a member of the community subjected to all this violence and these indignities? What might that witnessing have driven you to do?

Rebel?

Around 2 a.m., April 6, 1712, more than 25 enslaved individuals initiated the first uprising against colonial New York’s brutal slave system. (The British had already instituted draconian slave codes in 1686. And by 1700, New York’s city government would not permit more than three enslaved individuals to congregate. No slave over 14 could go out after sunset without a lantern to be clearly seen, nor was drinking allowed.)

The conspirators set fire to baker Peter Van Tilburg’s outhouse. (Raging flames could destroy a city a mile wide and a mile and a half long and composed mostly of wooden structures.) Then, the plotters—armed with muskets, hatchets and swords—killed nine whites who tried to extinguish the fire. But New York’s white colonial militia eventually captured 70 presumed conspirators and ultimately executed 26 (20 were hanged, three were burned at the stake, one individual was roasted, another was broken on the wheel and another starved to death; all were beheaded and their bodies left to rot).

These 26 Africans were likely interred in the Negro Burial Ground, the oldest and largest slave cemetery in the United States. (Approximately 15,000 enslaved bodies found their final resting place in a sacred, seven-acre space during the 18th century in what is now Lower Manhattan’s City Hall area. (Gibney, publisher of this journal, is also situated atop the African Burial Ground and, in its formal Land Acknowledgement, honors “both the spirit of those buried here and those who fought for the protection of this site for current and future generations.”) Interestingly, the Negro Burial Ground opened the year of the revolt, when Africans comprised approximately 17% of colonial New York’s nearly 5,900 inhabitants.) New York also maintained the second largest urban slave population. (Only Charleston, South Carolina—the United States’ biggest slaving port—could lay claim to a greater number of enslaved individuals in a city.)

British slave traders abducted a large number of Coromantee and Paw Paw (people from the Akan-Asante kingdom in modern-day Ghana) and dragged them to New York City’s port. (This particular trafficking in Africans had occurred between 1710 and 1712.) The Akan-Asante/Paw Paw/Coromantee comprised the largest percentage of the 1712 freedom fighters, where twenty percent of the participants had African names, such as Mingo and Quash.

The Coromantee came from a fierce, militaristic culture. They led dozens of slave rebellions—mostly in the Caribbean—and gained such a reputation that white slave traders proposed a ban on the Akan’s importation. (Before the 1712 Revolt, the Coromantee had likely taught some already-enslaved New Yorkers guerrilla warfare.)

That said, members of the Akan-Asante kingdom had also enslaved fellow West Africans. So, the colonial New York’s recently-enslaved Coromantee and Paw Paw had likely witnessed bondage in their homeland. But the Akan system resembled medieval serfdom rather than the British colonies’ chattel slavery. For starters, enslaved individuals in West Africa were treated as people not property. They could work for themselves, become equals in their enslavers’ society, inherit land, have greater rights and know their children would not be enslaved—all rare opportunities in the colonies.

Hence, New York’s enslaved Coromantee—to their British masters’ dismay—had different expectations about bondage, such as “humane treatment, clearly-stated laws prescribing master-slave relations and rewards for faithful service.” These enslaved Coromantee undoubtedly resented colonial bondage because their expectations were rarely met in New York. Notably, some of the freedom fighters—during their trials—testified they had revolted because they had endured “hard, brutal usage” by their white enslavers. Because of their background, the enslaved Coromantee/Paw Paw found colonial bondage profoundly unjust.

I wrote four poems about the 1712 Revolt, an uprising likely prompted by undue colonial bondage. These works appear in Boneyarn, my collection about slavery in New York City. For research and to prime my artistic pump, I read a number of articles and seven books. Three works mentioned men and women had participated in the revolt; one text said only men; another book provided neither names nor genders; another text focused on New York slavery decades after the revolt (from 1770 to 1810). The final book made no mention of women but named some male participants (such as Peter the Doctor, Robin, Tom, John—a Spanish Native American—and the likely-Coromantee Cuffee; enslaved by Van Tilburg, Cuffee and John started the outhouse fire).

The fact that no historian had named any female participants troubled me.

Image Description: Book cover of Boneyarn Poems by David Mills

Only in Dr. Jill Lepore’s essay “The Tightening Vise,” (published in a book entitled Slavery in New York), did I finally come across three enslaved, female freedom fighters’ names—Lily, Sarah and Abigail. On noticeably-darkened page 80, Lepore matter-of-factly states about the implicated freedom fighters: “their fates are noted below.” Then, using smaller print—relative to the book’s normal-sized print and cream-colored pages—Lepore creates three columns “Name/Owner/Fate.” She places an asterisk beside the “fates” of Sarah and Abigail: “hanged.” (Lilly was discharged.) Also, on that same page’s bottom right corner—in even tinier than the already tiny print—Lepore writes “Either Sarah or Abigail was pregnant, and her sentence suspended until after giving birth.” I had likely missed Lepore’s microscopic, italicized footnote a dozen times (a note which read like an erasure, albeit a likely unintended diminishment).

My book was already in production. But I sought time to give poetic texture to the dearth of information about either Sarah and/or Abigail. In a compressed, creative fever, I wrote a triptych about what I knew and would never know about these two enslaved ancestors.

New York’s white enslavers preferred young, enslaved women as domestic servants to cook, clean, wash clothes, make trips to the market, sew and care for white, colonial-settler children. Enslaved men toiled at largely non-domestic tasks, such as as mariners, blacksmiths, lumberjacks, farmers, tanners, and chimney sweeps.

My desire to unearth these women’s names had come from a sincere place but also a potentially sexist arena. I acknowledge my politically-correct, 21st-century self. I wanted these women’s names (say her names, say her names) and their courageous stand to receive historical recognition equal to what their male counterparts received. But I also wondered if I deemed the enslaved men’s work more valuable. I wondered if I had searched for enslaved women’s agency outside the domestic sphere. Looking at typical 18th-century division of work roles, I might have privileged men’s work, (for example, carpentry) over women’s work (for example, cooking where enslaved females lived in their enslavers’ cellars/kitchens).

Had either Sarah or Abigail, like so many other enslaved women and their children, slept in damp basements or cold, dark kitchens, drinking polluted water when they were pregnant? Pregnant, had either Sarah or Abigail wondered about other mothers and children in similar conditions?

Had either woman spotted the countless cavities in enslaved children’s mouths, knowing that those caries resulted from those children’s poor diets—high in sugar, corn, molasses, wheat and flour? (Seventy percent of enslaved children under six had dental defects.) Were Sarah or Abigail troubled to notice the stunted growth and rickets in enslaved children? Did they know that, after infants born into slavery, enslaved women of childbearing age had the second-highest mortality rate?

Surely both Sarah and Abigail would have known white masters discouraged—even stopped—their enslaved from marrying or bearing children, because of the small spaces enslavers and enslaved resided in together.¹ Might all this horrific witnessing–and the desire to give their unborn child a better life—have driven these three women, Lilly included, to take up arms and risk their lives for the possibility of freedom?

In 1962, Malcolm X asserted, “The most disrespected person in America is the Black woman. The most unprotected person in America is the Black woman. The most neglected person in America is the Black woman.” Words such as Malcolm’s plus the endless “ifs” and scant attention to Sarah’s and Abigail’s difficult lives and agonizing deaths might have compelled me to write the poetic triptych/tribute—“Which One,” “Which, Too,” and “Sundered.” We will probably never know which one of these women had been kept alive, deliberately, until childbirth, before being executed. But creative space and centuries of silence, gave me room to conjure. To imagine. To honor.

My triptych’s opening piece, “Which, One,” largely contains questions, each starting with the phrase “which, one…” and imagining either the pregnant Sarah’s or Abigail’s participation in the revolt.

Which one, with half-basket hilt, is crouched near a sugar maple’s long-winged seeds / and sweet eventual sap, which one / is nurturing fetus and fire in her belly / while planning to birth/murder?

Were Sarah, Abigail and Lilly members of the Coromantee, not unlike Jamaican Maroon warrior Queen Nanny or, purportedly, Denmark Vesey?

The triptych’s second section, “Which, Too,” explores either Sarah’s or Abigail’s imprisonment in the City Hall dungeon, above which were spaces such as the Supreme Court and the Mayor’s residence.

“In a pinched and dank corner cell… / beneath two floors and black robes…beneath plaintiffs and gavels…:: The City Hall dungeon where in darkness / lies a woman with child.”

Not unlike “Which One’s” repetition, and to underscore how either the pregnant Sarah or Abigail is shackled in a dungeon while the City’s business continues above her, “Which, Too” contains a series of beneaths to anchor consecutive phrases.

My triptych’s final section, “Sundered,” captures the moment of birth and imagines the child orphaned after its mother—either Sarah or Abigail—has been hung.

Which rebel kept alive…until she delivered her dark cargo?…there would be no wean in the fullness of time…will there be, for a three-year-old, chores?…

When will the death of its mother and a life of bondage dawn

on this child like a bitter morn?

The triptych explores Sarah’s and/or Abigail’s courage and sacrifice and aims to imaginatively flesh out the “fact gap” white colonial chroniclers left and contemporary historians, to a considerable extent, either glossed over or ignored.

What might Sarah and Abigail not have known except, perhaps, in their bones? That 85% of examined, enslaved adults had bone diseases? That some of the trauma to enslaved New Yorkers’ skeletons mirrored what appeared on the skeletons of enslaved individuals who toiled on southern plantations? That one-third of enslaved children’s skulls had fused early, suggesting that by age four, they were already carrying heavy loads on their heads? That these children never experienced what we think of as childhood?

That nearly half of the skeletons of young adults showed arthritis–a condition more commonly starting in middle age? That the appearance of arthritis, intimate that these young adults endured constant and difficult labor? That most enslaved children who died before the age of eight were born in New York? That most enslaved New Yorkers who reached adulthood were born in Africa, because these individuals had, early in life, been well-nourished and not forced to work? (Still, almost half the enslaved children who survived the Middle Passage died between age 15 to 24 in New York, due to the backbreaking slave system.) That many enslaved New Yorkers suffered levels of lead poisoning high enough to cause neurological and behavioral harm?

That three centuries later, as Sarah’s and Abigail’s remains rest in the Negro Burial Ground, might they feel these bitter truths deep in their bones?

Duane Street functions as the burial ground’s northern border and, in 1809, the street had been named for James Duane, a signer of the original US constitution. Duane’s father, Anthony, profited from, amongst other things, the slave trade. So, Duane Street borders and might cover Sarah’s and Abigail’s bodies, borders and might cover the orphaned and unnamed child either Sarah or Abigail bore. Exactly who that unnamed child’s mother was, is lost to history; but Anthony Duane, a white, triangle-trade profiteer who amassed wealth buying and selling black women like Sarah and Abigail, is not.

Say her names; say her names.

NOTE

- Because enslaved and enslavers lived in the same tight quarters, the enslavers were not necessarily desirous of the enslaved having children or spouses. The supposed thinking was that white, colonial enslavers would rather abduct/enslave individuals who were, let’s say, five and up and able to work. The white enslaver would also see an enslaved infant as “taking up space” in the home and not capable of being “productive.”

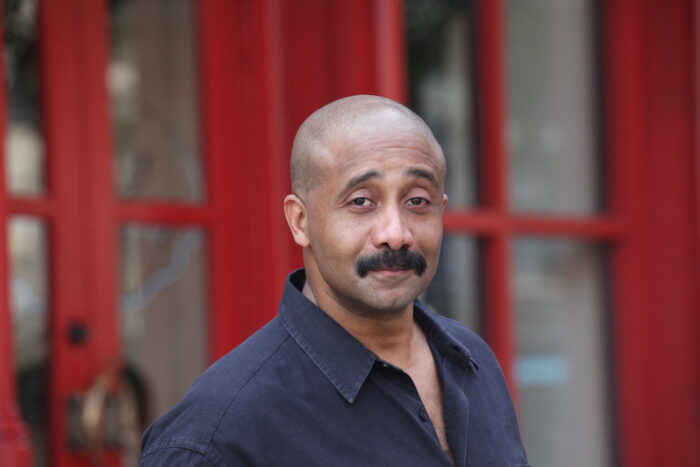

Image Description: A Black man with close-cropped hair and a wide dark moustache gazes towards the camera with his body turned slightly to one side. We see him only from sternum up, and he’s wearing a black shirt opened at the collar.

Photo by Luigi Cazzaniga.

Mr. Mills holds an MFA from Warren Wilson College and master’s from New York University. He’s published four collections: The Dream Detective, The Sudden Country, After Mistic and the bestselling Boneyarn—the first book of poems about slavery in New York City. His poems have appeared in Ploughshares, Colorado Review, Crab Orchard Review, Jubilat, Callaloo, Obsidian, The Common, Worcester Review, Rattapallax, The Literary Review, The African-American Review and Fence. He has also received fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts, Breadloaf, the Lannan Foundation, the Queens Council on the Arts, the Bronx Council on the Arts, the Poetry Society of Virginia North American Book Award, Flushing Town Hall, Washington College, the Brooklyn Non- Fiction Prize and The American Antiquarian Society. He lived in Langston Hughes’ landmark Harlem home for three years (was a recipient of the Langston Hughes Society Award) and wrote the audio script for Macarthur-Genius-Award Winner Deborah Willis’ curated exhibition: Reflections in Black: 100 Years of Black Photography. The Juilliard School of Drama commissioned and produced a play by Mr. Mills. He has recorded his poetry on ESPN, RCA Records, and the National Parks Service and has had poems displayed at the Venice Biennale and Germany’s Documenta art exhibition.

Support

Venmo: @DMills-267

I’m the founder and Executive Artistic Director of South Chicago Dance Theatre (SCDT), a multiracial and multicultural dance company now in its sixth season. SCDT creates artistic experiences for all people through its vibrant repertory dance ensemble and innovative educational initiatives, bridging the gap between concert dance and community. I am also beginning a career as a freelance choreographer, and this season’s eight world premieres includes my first full evening-length work, Memoirs of Jazz in the Alley.

Memoirs opens June 10, 2023 at the Auditorium Theatre of Chicago, as a part of the Auditorium’s Made in Chicago series. It’s the culmination of my time as one of six Chicago Dancemakers Forum 2022 Lab Artists, a year of choreographic tool-building. Isaiah Collier provides the soundscape of the piece with newly composed and arranged music played by his band Isaiah Collier and the Chosen Few. Renowned theater and opera designer, Rasean Davonte Johnson, creates scenic and projection design, transporting the audience from the proscenium stage to an outdoor jazz festival on Chicago’s south side in the early 1970s.

This work draws inspiration from my decades among the Chicago jazz community.

Through the creation and presentation of Memoirs, I desire to bring awareness to the significance of a vibrant cultural happening that contributed to jazz as we hear and see it today in Chicago. Over the last year, I’ve found that the process of making dances helps me to connect to areas of life that I thought were lost, discover parts of myself that I didn’t know existed, and experience the reclamation of cultural narratives of importance to those in my community.

Image Description: Closeup of a jazz musician in a plaid dress shirt playing the Saxophone.

My maternal great grandmother, Josephine Griffin Jones, came to Chicago during the Great Migration and settled into the once-known Black Belt on Chicago’s south side, bearing a suitcase full of hundreds of handwritten prayers for herself, her immediate family, the country, and world at large. Twenty years earlier, my paternal grandmother also settled in the same neighborhood only a few blocks away. This area between 30th and 70th streets was the sole place these Black migrants could inhabit in Chicago.

My family has been on the city’s south side now for almost a century and seen the multitude of changes in the community spanning the Great Depression, Civil Rights Era, Black Renaissance and the snowballing effect of gentrification. For much of my childhood, the city’s south side was my entire world, and I unknowingly had rooted much of my identity in its geography, history, and culture.

In the 1950’s, a man named Arthur Pops Simpson began spinning his favorite records once a week outside of his home in the Alley on 49th and Champlain, a block also known as the Valley. Before long, other amateur DJ’s joined Simpson and people from the community gathered to listen. A congenial competition amongst DJ’s emerged.

One Sunday, my father, Jimmy Ellis, a young alto saxophonist, brought live sound to the affair–the first musician to do so. He was then credited for being one of the founders of Jazz in the Alley, a pseudo-impromptu jazz festival and community gathering that took place on the city’s south side for decades. Not only did he perform there but he also curated artists from across the US to play at Jazz in the Alley.

These free parties would go late into the evening, continuing even after the first set in the alley, at the nearby Spanish Village. This impromptu cultural happening served as a breeding ground and meeting place for some of the country’s prominent jazz musicians, local legends, visual artists, poets, activists and organizers, coming together with children, families, community members, and people from all walks of life.

“It was a place where people could come and feel a part of each other,” Ellis said in a 1992 interview for Chicago Tribune.

As the community transformed the event from record-listening party to live music festival, there was a great need for security and infrastructure to support the event’s growing attendance. After a non-fatal shooting in 1978, the city shut down the original Jazz in the Alley.

Jimmy Ellis worked for a time to continue producing the event as a formal festival which began in 1979, and factions of community members also hosted iterations such as Back Alley Jazz, an effort to preserve this south side tradition. Years later, Ellis also founded the annual Valley Festival in a vacant lot across the street from Pop’s original alley site. This unique socio historical movement, shaped in many ways, the ethos of jazz in Chicago for decades.

Aside from his work at Jazz in the Alley, Jimmy performed nationally and abroad, educated some of Chicago’s most influential jazz artists, and practiced visual art. In July 2021, he passed away at age 91.

For many reasons, from the time that I was born, I was not permitted to live with my father or to be fully integrated into his personal life. Not having a strong presence in his life also meant that, in his death, I would not be considered. Chicago’s Hyde Park Jazz Festival hosted a celebration of life for my father a month or so after his passing. At that event, they announced that some rare interview footage of Jimmy existed. I was curious to see this footage, hoping that, within it, I could encounter some missing pieces of my father or even myself. I approached the organizers and immediately sensed their reluctance to speak with me. They gave a cold explanation that I would be permitted to view the footage only if and when it was made available to the public.

The circumstances into which I was born prevented me from gaining access to my father’s personal effects. I had no proprietary rights; his public work and persona belonged to gate keepers at various institutions. As an artist and daughter, I could not accept that others controlled my access to my father’s legacy.

Image Description: Closeup of a drum set.

Below are a few quotes from local newspapers that touch upon Jimmy’s impact as a musician on the city’s south side.

“Audiences have roared their approval over the years, reflecting the emotionally charged quality of Ellis’ playing. It’s as if everyone in the house recognizes the utter authenticity of this music, a viscerally effective brand of improvisation forged on Chicago’s South Side. ‘It’s hard for me to put into words exactly what the Chicago sound is, but I think it’s there in my music, and in the music of many other musicians,’ says Ellis, ‘In part, the Chicago sound is swing,’ adds Ellis, ‘but it’s also a feeling—an emotional feeling you put across in the music.’ Yet that hyper-charged manner of expression is not easily acquired today, for musicians such as Ellis learned it the old-fashioned way, growing up on the South Side in an era when jazz pulsed from practically every street corner.” (Do312.com)

Longtime Chicago Tribune critic Howard Reich describes Charlie Parker as one of Jimmy Ellis’s greatest influences and notes the bebop era of the 1940s and 1950s as also having a lasting impact on his sound “Indeed, the south side practically courses through Ellis’s music” (Chicago Tribune)

“’I was born 1930—it was hard times, the Depression,’ says Ellis. ‘I saw people go hungry. … I feel it deeply. Like I tell my students: If you keep living, you might learn something. You’ve got to know what it is to be hungry. If you’ve never been in love, you don’t know how to play a love song. You can play the notes, but you can’t feel it.’

“‘God bless the child that’s got his own,’ continues Ellis, quoting the famous lyric. ‘When I played that song, it touched me very deeply. I go back in my mind to when I was a child. I remember in the Depression people would come to our back door, and my mother would feed them.’” (Chicago Tribune)

“…life lessons Jimmy has learned can be heard in every note he plays” (Chicago Tribune)

As I make this new dance work, I wonder; what life lessons can I learn from listening to my father’s music, the music he liked, and his work as a community organizer?

Jazz, a ubiquitous, proudly American ambassador to the world, has African roots that are often misappropriated, misinterpreted, glossed over, or forgotten.

“Whites plagiarized the wealth of fertile material that Black Americans produced, material which is glorified only after it had been absorbed and ‘whitened,’ as in such cases as George Gershwin, Jerome Robbins and Elvis Presley. As a result of such theft, jazz dance was infused with European influences. Jazz dance’s rhythmic density and complexity were flattened, which caused the body to resist its natural weightiness, blurring and/or extinguishing its Africanist origins when appropriated by Whites.” (Julie Kerr-Berry)

Memoirs of Jazz in the Alley celebrates jazz as an Africanist form with roots in the Black body. It is a force of reclamation, paying homage to the narrative of this southside community for the first time through an evening-length performance.

Much of my pre-adolescent childhood was spent sitting in the back of the Jazz Showcase, a prominent nightclub, where I watched the colorful interactions between the musicians, bar staff, and audience members. My mother was a waitress there for most of her career and, through her, I met many of the greats affiliated with Jazz in the Alley and the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. Although in making my new dance, I do not seek to reference the Jazz Showcase itself, its sounds, colors and the feeling of being there are part of the fabric of my childhood. They serve as a tonal catalyst for the making of Memoirs.

Like all endeavors, dance has always reverenced and universalized the white and male perspective as its baseline. One of my overarching missions as a choreographer is to reposition my voice–a Black woman’s voice–as universal. Rather than seeing myself as other, I view my disposition as one that can be valued in a multitude of communities and by a diversity of people. While Memoirs comments on a Black experience, I hope that audiences can view and appreciate it beyond the lens of Black dance. I hope audiences become so deeply immersed in the details of this specific community that they’re inspired to take a closer look at their own family and community histories, cultures, and stories.

Below is a library of images taken by Jimmy Ellis and Kevin Harris during Jazz in the Alley. I happened to come across this gallery while doing a Google search a few years ago and often return to look through and be inspired by these images.

JAZZ IN THE ALLEY • Google Arts & Culture

“Portrait of a Chicago Community 1966-1976”

¹“Africanist Elements in American Dance” by Julie Kerr-Berry, Rooted Jazz Dance: Africanist Aesthetics and Equity in the Twenty-First Century, ed. Guarino, et al., University Press of Florida, 2022

Image Description: This photo is of an African American woman with a nose ring and gold earrings wearing a black tank top on a black background. Photo by Michelle Reid.

Kia S. Smith is a Chicago native. She holds a BFA in Dance from Western Michigan University and an MFA from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee where she was an Advanced Opportunity Program Fellow. Kia is the Founder, Resident Choreographer and Executive Artistic Director of the South Chicago Dance Theatre. She is also the founder of SCDT’s signature Main Company and Emerging Artist Program, Education and Community Programs, Choreographic DiplomacyTM program, South Chicago Dance Festival as well as choreographic and administrative fellowships. Kia’s recent and upcoming commissions include Madison Ballet (2021), Chicago Repertory Ballet (2022), the Institute For Contemporary Dance at Houston Contemporary Dance Company

(2022) and Ruth Page Civic Ballet Training Company (2022). In 2018, she received the inaugural Young and Ambitious Entrepreneurship Award from the Metropolitan Board of the Chicago Urban League and was chosen by the New York City based Stage Director’s and Choreographers Foundation as a member of the national Observership class. Kia is a recent recipient of a 3Arts Make A Wave award (2021), the Ann & Weston Hicks Choreographic Fellowship at Jacobs Pillow (2021), the Chicago Dancemakers Forum Lab Artist Award (2022) and she is a participant in the Artist in Residence “AIR“ Program at the Cliff Dwellers Chicago. Kia served as choreographer for Chicago Opera Theatre’s world premiere of Quamino’s Map (2022).

Website

www.southchicagodancetheatre.com

kiassmith.com

Facebook

@SouthChicagoDanceTheatre

Instagram

@southchicagodancetheatre; @kia_s_smith

Support

Zelle: kia.s.smith@gmail.com

“escape is an activity, not an achievement.” -Fred Moten

my feet on the earth

my hands rising slowly

noticing

each part

of my body

the dancefloor

a yard

a porch

a circle

sometimes an alleyway

the dancefloor

a clearing

a corner

a quiet

the dancefloor

is a fugitive sanctuary

is a space I escape to

is a space I return to

is a space where I find myself again

and again and again

For the past two years, I have been cultivating a body of work called Black Fugitive Folklore that honors the historic traditions of marronage* and Black fugitivity*. Through an iterative, vernacular, and emergent creative process; this work explores the intersections of fugitive practice, flight, return and refusal. It weaves together mixed-media, soundscapes, ritual performance and social practice. Black Fugitive Folklore is a sacred meditation of embodied liberatory praxis. How can fugitivity inform current movements for liberation and reparations? How can marronage disrupt the algorithms of empire?

Moving with these questions through study, creative ritual and listening, has called me to be in my body in new ways. To listen to her, to be in relationship, and in conversation. My body moves in waterways, under trees, with my feet in the grass. What is she carrying? What is she saying? And how? I attempt to put words to gestures, make meaning of the motion of my hands, find the metaphors that twist my face, and write the poetry of the body.

This body, that only a few generations before me, would have been bound to something beyond herself. Might have been bound to a plantation economy, or a slave ship, or a machine, or to somebody else’s time. So, I move slowly, gently, deliberately, wildly. I record my movements, listening to what the body reveals through its dance, and I write. I reflect back to her what I see, through my own mirrored listening. Sometimes what I see is familiar. Sometimes it is unrecognizable. Sometimes what I witness surprises me. Often, I am reminded that this body is made of both star stuff and scar tissue, a body with a memory that carries cells way beyond my lifetime. My body feels with depth, in ways that my mind does not always have the capacity to understand. Through movement, I escape the boundaried limitations of the mind, and open myself to the wisdom of my body.

In 2020, I took a deep dive into all things Black fugitivity. There lived in me a profound desire to learn about marronage, and undergrounds, and all the ways that our ancestors freed themselves. At that time, we were being inundated with daily news of police murders of Black people, of exacerbated health disparities amidst a global pandemic, and the rising threat of white nationalism coupled with the reality of racialized capitalism. I was looking for a way out, or beyond. Where were the spaces we could live on the outside of subjugation? What were the ways our ancestors fought back, liberated themselves, and undermined the apparatus of the plantation? How did we survive the impossible? There had to be blueprints, balms, recipes, ways of being that could help me better navigate this moment.

the dancefloor

is where I meet my body

where I see her

feel her

where I can listen to her ebbs and flows

her pacing

her rhythm

her patterns

the dancefloor is a fugitive sanctuary

where I find refuge

where I find flight

where I find levity

where I feel my own weight

my body

on the earth

of the earth

tethered

the dancefloor is a fugitive sanctuary

where I find myself again and again

and again

Watch the dance floor is a fugitive sanctuary by Jessica Valoris below:

There is an extensive list of books, talks, documentaries, music, slave narratives, and artifacts that have guided my studies. The book Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South by Stephanie M.H. Camp was particularly resonant. Camp introduced me to the term: petit marronage, where self-liberating ancestors would escape to the woods temporarily before returning to the places where they were enslaved. Petit marronage was most often exercised by Black women, who were more confined to the plantation by gendered labor roles and familial obligations, and who were more severely punished for acts of defiance.

Black women would escape to the woods for days, weeks, sometimes months at a time. Sometimes they would find aid in the form of food, clothing, and other provisions, left for them by enslaved people on nearby plantations. Women would find refuge in the swamps and the woods. There were many motivations to escape: to evade punishment or torturous conditions, to escape sexual advances and violation, to ground themselves, to find some kind of solitude, rest, and sanctuary. Evading capture and traversing all the unknowns of the wild, for a moment, their time and their bodies were their own.

the subtle motion of my wrist, my ring finger, my right eye

finding my own balance

finding my own way

twisting and turning

and shifting

and going back

and going back

and going back

and moving it forward

and moving it through

and moving on

the dancefloor is a fugitive sanctuary where

I find myself

again

and again

and again

In Closer to Freedom, Camp goes on to describe other ways that enslaved people challenged the systems of control by reclaiming the movement of their bodies. She specifically talks about secret dance gatherings in the woods where enslaved people made space for play, joy, style, and celebration. Amidst a slave economy that demanded the absolute control over Black bodies, and at the risk of severe punishment and retaliation, Black people continued to refuse total subjugation.

Today, fugitive practice is echoed in the ways we move, make music, tell stories, do our hair, create family, cook, commune with the land, and beyond. Fixing a plate is a fugitive practice where enslaved people would leave food and provisions in the woods for maroons. Cousining is another fugitive practice that refers to the ways Black people created kinship networks across bloodlines and geographies to evade capture. Extensive knowledge of the waterways, land, and night sky were ancestral technologies that supported self-liberating people in surviving the unknown. Big and small acts of sovereignty transpired both on and off the plantation by enslaved peoples, free Blacks and those in the in-between. Through truancy, secret gatherings, harboring, care, and networks of solidarity; our enslaved ancestors seeded a legacy of embodied liberatory praxis that carries on.

Petit marronage reminds me that fugitivity is not just about escape, it is also about a return to our loved ones. It is meeting each other on the dancefloor, under the cover of night, with all our hope and all our mess and all the risks, again and again. Full-bodied dance and audacious joy are fugitive practices we can return to.

In 2021, SpiritHouse North Carolina facilitated a haiku-writing practice. Inspired by this daily exercise and other musings on liberation, a group of dance practitioners called Black August Movement in Motion responded to prompts using our bodies. For 31 days, I devoted myself to daily movement and writing. Through collective study, experimentation, and improvisation⎯a series of short performance meditations emerged.

Remembering that we have been here before, and we will find a way through, I return to these fugitive practices. Again and again, we are (un)mapping and cultivating new ways of knowing; being fully present with our environments, with our ancestors, and with each other. In the face of growing violence and erasure there is also an expanded opportunity for liberation, care, and visionary resistance. There is no manual, but there are guides encoded into our being. May we create the sanctuaries we need to tend to our sacred bodies, receive its wisdom, and allow it to move us through.

my hands rising slowly

my feet on the ground

sole to soul

soul to soil

the dancefloor is a portal

is a space in between life and living

all that we do with this body

all that we do with this breath

all that we be with this lifeforce

in the in-between

“…amidst it all, we just keep making space, because that’s all we can do.” -Saidiya Hartman

**Black fugitivity refers broadly to the ways that Black people evade capture, and imagine and actualize a world beyond and in refusal to the oppressions of racialized violence.

**Marronage is the practice of enslaved peoples’ escape and sovereign community-building in the wilderness, often on the borders of plantations or deep in the swamps or mountains.

** Black August is a month-long tradition of collective study, disciplined health and wellness, and political education that honors Black political prisoners and their organizing towards Black liberation.

Image Description: Light-skinned Black woman sits wearing a flowy earth-toned skirt and shirt set and red Converse sneakers. Photo by Imagine Photography – Kea Taylor.

Jessica Valoris is a Washington DC based artist and community facilitator. Weaving together mixed media painting, sound collage, and ritual performance, Jessica creates sacred spaces that activate ancestral wisdom, personal reflection, and community care. Inspired by the earth-based traditions of her Black American and Jewish ancestry, Jessica explores ideas through the lens of metaphysics, spirituality, and Afrofuturism. Using art as a catalyst for collective healing, Valoris affirms the joy and vitality of Black people, complicating flattened histories of oppression, and creating space for affirmative celebration and re-definition. Jessica values collaboration with community-based cultural workers and collectives, and her work supports culturally- relevant wellness and resilience. Jessica Valoris is a Fellow with the Public Interest Design Lab, and an alumna of the Intercultural Leadership Institute and Halcyon Arts Lab. Iterations of her most recent body of work, Black Fugitive Folklore, have been shown at the Phillips Collection, The Kreeger Museum, Africana Film Festival, and Brentwood Arts Exchange. Her interactive installation, “Phone Home” debuted at the George Washington Carver Museum and Cultural Center in Austin, TX. Her interactive “Xigga Project” and “Dope and Different” portrait series has been featured at Anacostia Arts Center, Culture Coffee Too, Afrotectopia NYC, and Harvard University’s Black in Design Conference. Jessica has been an ensemble member of Body Ecology Performance Ensemble, and is a co-creator of the Colored Girls Hustle Hard Mixtape.

Website

www.jessicavaloris.com

Instagram

@JessicaValoris

Photo of Eva Yaa Asantewaa (she/her)

Image Description: In this selfie, taken in her home office,

Eva Yaa Asantewaa is wearing a black turtleneck sweater and

looking forward with a cheerful grin. She is a Black woman with luminous,

medium-dark skin and short gray hair. She’s positioned in front of a room

divider with an off-white basket-weave pattern.

Eva Yaa Asantewaa (she/her) is Editorial Director for Imagining: A Gibney Journal and, from 2018 through 2021, served as Gibney’s Senior Director of Curation. She won the 2017 Bessie Award for Outstanding Service to the Field of Dance as a veteran writer, curator and community educator. Since 1976, she has contributed writing on dance to Dance Magazine, The Village Voice, SoHo Weekly News, Gay City News, The Dance Enthusiast, Time Out New York and other publications and interviewed dance artists and advocates as host of two podcasts, Body and Soul and Serious Moonlight. She has blogged on the arts, with dance as a specialty, for InfiniteBody, and blogs on Tarot and other metaphysical subjects on hummingwitch.

Ms. Yaa Asantewaa joined the curatorial team for Danspace Project’s Platform 2016: Lost and Found and created the skeleton architecture, or the future of our worlds, an evening of group improvisation featuring 21 Black women and gender-nonconforming performers. Her cast was awarded a 2017 Bessie for Outstanding Performer. In 2018, Queer|Art established the Eva Yaa Asantewaa Grant for Queer Women(+) Dance Artists in her honor. In 2019, Yaa Asantewaa was a recipient of a BAX Arts & Artists in Progress Award. She is a member of the Dance/NYC Symposium Committee, Founding Director of Black Diaspora, and Founder of Black Curators in Dance and Performance.

A native New Yorker of Black Caribbean heritage, Eva makes her home in the East Village with her wife, Deborah. Sadly, their best-cat-ever Crystal traveled over the Rainbow Bridge on February 18, 2021.

Photo of Monica Nyenkan by Jakob Tillman

Image Description: Monica Nyenkan is the daughter

of African immigrants. She has dark brown eyes and hair.

In this photo, her hair has two-strand twists.

Monica Nyenkan (flexible pronouns) is a Black queer artist, administrator, and emerging curator from Charlotte, NC. Graduating from Marymount Manhattan College, Monica received her Bachelor’s degree in Interdisciplinary Studies, concentrating on administration for the visual & performing arts.

Currently based in Brooklyn, Monica has interned and worked with Rachel Uffner Gallery, Gallim Dance, Ballet Tech Foundation, Movement Research, and 651 ARTS. She’s produced community-based engagements and art events throughout NYC for the last five years. She acted as a consultant and advisor to an award-winning project, LINKt: a dance film. Most notably, Monica co-curated WANGARI, a pop-up art exhibition focusing on climate change, with the Brooklyn-based collective Womanist Action Network.

Monica currently works as the Gibney Center Special Projects Manager, managing programs such as Black Diaspora and Imagining Digital. In her free time, Monica loves to watch horror films and spend time with friends and family.

Photo of Anastasia Gudkova by Ksenia Ugolnikova. Anastasia is wearing a black top with a checkered blazer draped over her shoulders. She is a white woman with dark brown hair, wearing gold jewelry and light makeup. She is sitting down, leaning over a table with her arms crossed, and smiling into the camera. There’re string lights in the background of the photo.

Anastasia Gudkova (she/her), born in Moscow, Russia, is currently pursuing a B.A. in philosophy at New York University. While not a dancer herself, Anastasia has a deep passion and appreciation for contemporary dance and cultural programming and is fully dedicated to a future career in this sector.

Since 2019, Anastasia has worked as a Programming Assistant at MART Foundation, a non-profit, non-governmental foundation that supports contemporary culture on the international stage. Through this position, she has been exposed to a number of aspects of the performing arts world. Having worked on multiple projects both in the U.S. and internationally, Anastasia has been providing executive administrative assistance, events producing support, and logistics management.

Currently based in Brooklyn, Anastasia is a Gibney Center Presenting Intern since May 2022.